Advertisement

The trouble with air conditioning: 'Damned if you do, damned if you don't'

Resume

Over this scorching hot Fourth of July, millions of Americans from California to Louisiana will put their air conditioning into overdrive.

Who could blame them? AC can be a matter of life and death.

However, heating and cooling American homes accounts for nearly 20% of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions, which make the planet even hotter.

That’s why some people have started to rethink their relationship with artificially cold air, including journalist Chris George who asked his wife this provocative question in 2009: “Why don’t we go nuts and see if we can make it through the whole year without even turning it on.”

At the time George was living in a suburb of Phoenix, a city where summer temperatures often flirt with 120 degrees. And believe it or not, his wife was up for the challenge.

With no AC, George says it was tough to sleep at night. They draped wet fabric in front of a fan to cool the air. But at one point, the thermometer maxed out at 103 degrees inside.

“That meant that everything was high 90s — a 100 degrees,” George recalled. “You can’t pour milk into your cereal because the bowl will instantly warm it up to a temperature that’s kind of gross.”

George chronicled his experiment for the local paper, the Arizona Republic. Part of the idea was about saving money, he says. Most of it was about saving the Earth — or at least reducing his impact on it. George thought he could even inspire others to do the same.

“Some people responded to it in that way,” he said. “Some people said, ‘I am going to crank my AC up even more just to spite them.’”

Fifteen years later, George and his wife have left Arizona. But he says he still has a better tolerance for heat.

“Looking back, I know that was a privileged place to be [in],” he says. “Not everyone is in the position where this can be a choice.”

In fact, the Phoenix area has been breaking all kinds of heat records. More than 640 people died from heat exposure in Maricopa County last year. Last month was the hottest June in Phoenix history.

George’s experiment was featured in a 2010 book called “Losing Our Cool” by Stan Cox.

Cox chooses to live without AC in Salina, Kansas. He turns his unit on once a year just to make sure it still works.

Advertisement

“Air conditioning is kind of a Jekyll and Hyde situation,” Cox says. “It really is holding us back and it’s undercutting our ability to mitigate climate change. But it’s going to be necessary for adaptation to climate change.”

Cox’s book is a statistics-packed takedown of air conditioning’s grip on American life. He writes that cities in the Sun Belt — from Florida to Arizona — didn’t boom until the middle of the last century when the cooling power of AC was introduced to nearly every suburban home.

It allowed those homes to grow bigger. It kept our children indoors. It even influenced the rhythm of our sex lives.

When he wrote the book, Cox said that in one year Americans were so ravenous for cold air that we used as much electricity for air-conditioning as the entire continent of Africa.

But Cox abstains. On a hot day, he spends time in the cool confines of his basement. Like Chris George, he’s gotten used to warmer indoor temperatures, which scientists call the adaptive model of comfort.

“The temperature range we feel comfortable in is not a fixed thing like 68 to 78 or something like that,” Cox says. “It slides up and down the scale depending on the temps we have been experiencing in recent days and weeks.”

In search of ‘thermal delight’

All of this makes sense to Gail Brager, associate director of the Center for Built Environment at U.C. Berkeley. She studies something called thermal delight — the feeling when you step into a hot bath or put your hands around a warm cup of tea on a cold day.

Brager says our bodies crave that variety, and sitting in a sealed room for hours under a river of cold air is the opposite of delightful. “I call that thermal misery,” she says.

Brager says research shows that our use of AC resembles addiction: Americans binge on it, and when we try to cut back, we can’t do it. It tends to saturate our pleasure centers, “which then continually fuels this addiction,” she explains.

Brager is not making the argument that people should stop using AC. But she does say that using a fan or opening a window to move a breeze through the room would cut back on energy use and make us more comfortable.

Some of her colleagues at Berkeley have invented an office chair with a fan built into the seat, which keeps people comfortable without having to crank up the AC.

“Climate-based solutions should be our first approach,” Brager says.

Demand for AC surging around the world

The challenge is that people will be tempted to use more air conditioning as the planet gets hotter from human-induced climate change.

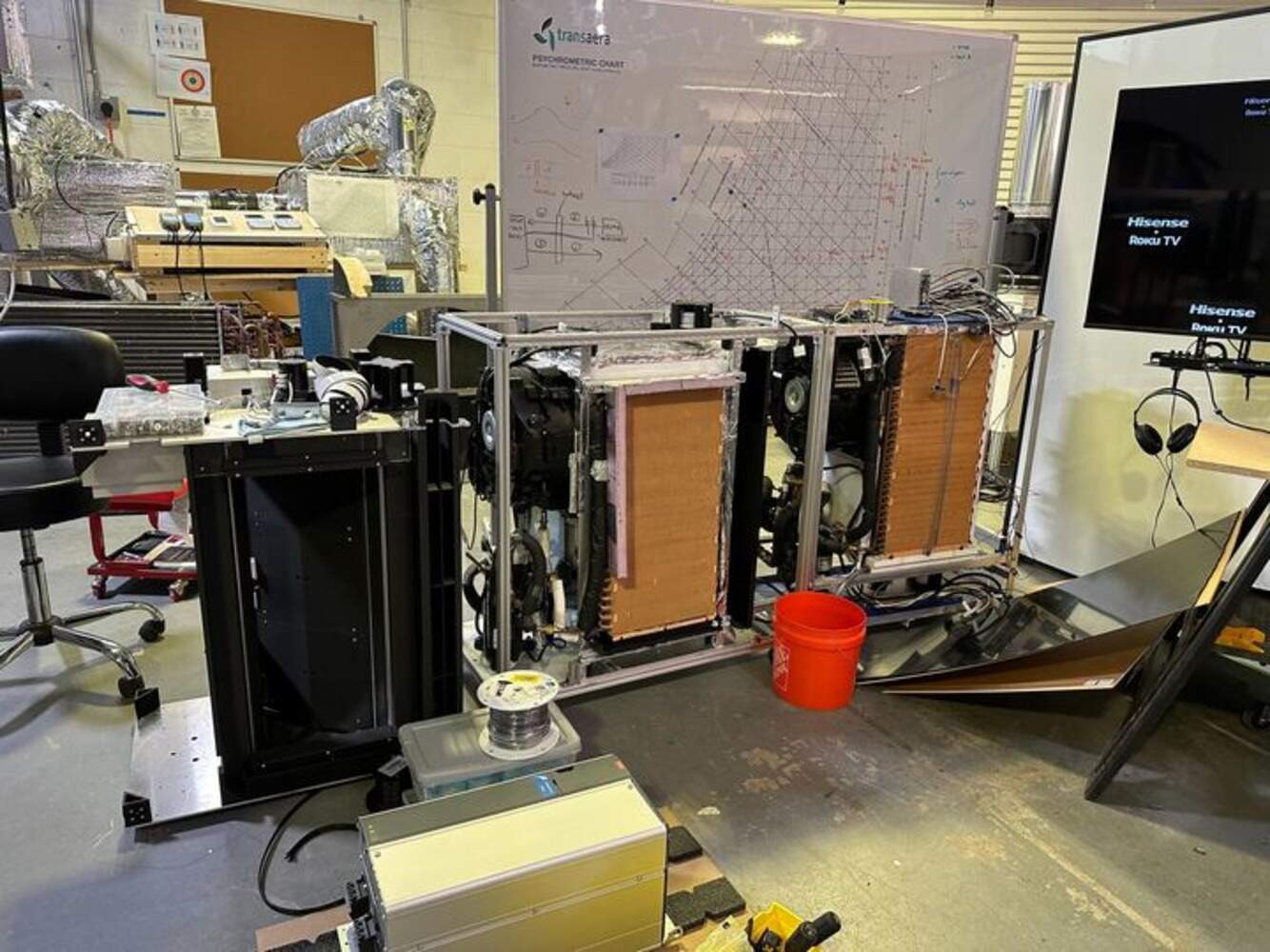

It’s an issue that the Massachusetts-based startup Transaera is trying to solve. A few years ago, the company was a finalist for the Global Cooling Prize — a competition sponsored by the Indian government to create affordable cooling technology that doesn’t warm the planet like traditional air conditioning.

Transaera’s portable AC unit looks like a piece of furniture you could imagine using in your living room. But it requires about 40 to 50% less electricity than conventional air conditioners, says co-founder Sorin Grama.

“The challenge is that refrigeration systems and cooling systems really struggle in hot and humid conditions,” he says. ”So any methods to improve the efficiency of an air conditioner can make a big difference.”

That’s because conventional air conditioners convert humidity into water, which then drips out of the unit. Transaera’s technology skips that energy-intensive step. It sucks humidity out of the air using drying materials that are a lot like those silica packets you find in a shoe box.

These improvements are essential to meet the needs of a growing middle class in hot countries like India, Indonesia and Mexico, Grama says. The International Energy Agency predicts that 10 new AC units will be sold worldwide every second for the next 30 years.

If every one of those units used conventional technology, it could be an environmental disaster, Grama says.

“In some places, they would have to build entire new grids to support that load for new air conditioning,” Grama says. “Where does that power generation going to come from? In many places like India, it will come from coal power plants.”

But as climate change intensifies, AC experts like Cox are not convinced that better technology will do much good.

From the 1990s to the early 2000s, government regulations drastically improved the efficiency of air conditioning equipment. But during that same time, the total amount of electricity consumed by AC doubled, Cox says.

“We’re using so much more air conditioning, it didn't matter that it was more efficient,” he says. “Don’t depend on efficiency to get us out of the predicament.”

Julia Corcoran contributed to this report.

This segment aired on July 3, 2024.