Advertisement

Commentary

I was the first baby born via IVF in the U.S. For the first time in my 42 years, ‘I feel like an endangered species’

Resume

For the first time in my 42 years of life, I feel like an endangered species.

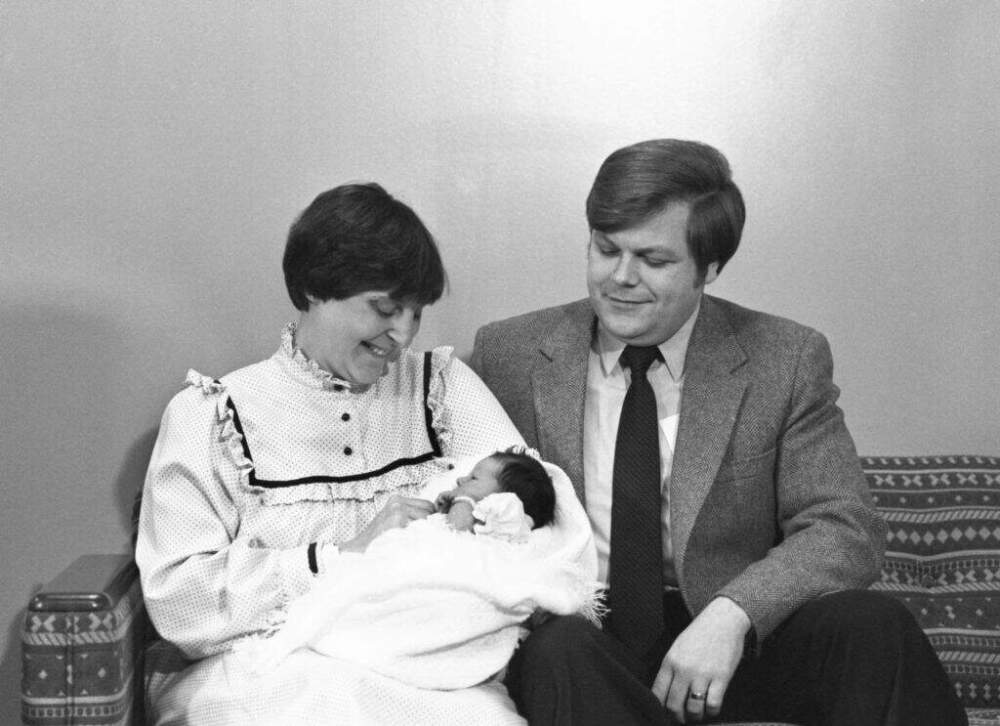

Back in 1981, I was born the first in vitro fertilization (IVF) baby in the United States, thanks to the foresight of Drs. Howard and Georgeanna Jones at the Jones Institute in Norfolk, Virginia, who brought the then-groundbreaking procedure of IVF to this country.

I was born in Virginia because at that time, IVF was unavailable in my parents’ home state of Massachusetts.

My parents experienced setback after setback, a story familiar to the millions experiencing infertility today. IVF was my parents’ only hope of creating the family they so desperately wanted after experiencing three ectopic pregnancies. So they flew monthly to Virginia, spending thousands of dollars on travel. They even rented a home in Virignia for the last month of my mom’s pregnancy before I was delivered by c-section. The treatments weren’t covered by insurance, which added even more financial pressure and strain to the already emotionally taxing procedures.

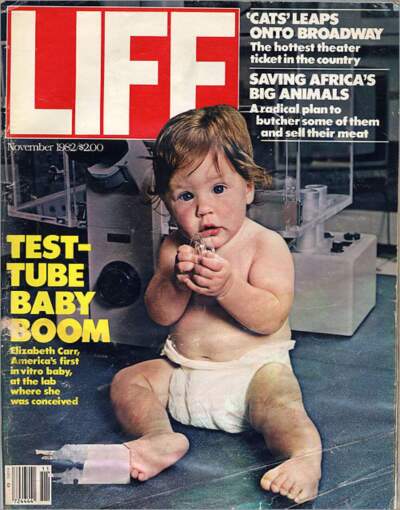

My birth, which made newspaper headlines and magazine covers around the globe, gave hope to millions of Americans who wanted to become mothers and fathers. It also marked the dawn of a new era of science-based medical fertility treatment known as assistive reproductive technology or ART. There’s a reason Robert Edwards, the doctor who pioneered this method, first used in England three years before I was born, was later awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine.

The reason my parents shared their names, faces and story with the media instead of remaining anonymous was so that people around the world could learn about IVF, a game-changing procedure. I share my story for the same reason.

Initially developed as a way to circumnavigate irreparable damage to a woman’s fallopian tubes, today IVF is used as a first line therapy for all causes of infertility because its success rate is so high. IVF is the single most effective assistive reproductive technology.

My parents’ greatest hope was that no one else would ever have to experience the heartache and strain they did in order to build a family. Forty-two years later, I still hold onto that hope.

But that got much harder to do last week in the wake of an Alabama Supreme Court’s ruling that frozen embryos can be considered “extrauterine children,” which means clinics could be held liable for wrongful death claims in the case of lab accidents. The ruling also complicates the storage and disposal of embryos. As I write this, three clinics, including the one at the state’s largest hospital — the University of Alabama at Birmingham — have paused IVF procedures (the CDC only lists seven assistive reproductive technology clinics in Alabama on its website.) And a major embryo shipping company has stopped transporting embryos to and from Alabama. More are sure to follow. This means residents of Alabama not only won’t be able to access treatment at home, they won’t be able to move their embryos to seek treatment elsewhere either.

Advertisement

No one understands better than the infertility community that embryos are not children. Success in IVF means bringing home a baby, not solely creating embryos.

Last week’s ruling was clearly written without a true understanding of the IVF procedure and a total disregard for the science of assisted reproductive technology. No one understands better than the infertility community that embryos are not children. Success in IVF means bringing home a baby, not solely creating embryos. The latter is simply one of many complicated steps one has to take in order to even have a chance of having a live birth.

One in six people of reproductive age are impacted by infertility globally and in the U.S. about 2% of all births annually involve IVF — that’s about 8 million born since I was. The procedure is used for a variety of reasons, including fertility loss after cancer treatment, a desire to delay having children, military deployments and the ability to screen for devastating genetic diseases.

IVF is a complicated multi-step process that includes hormone injections, egg retrieval and an embryo transfer. It is a delicate dance of financial resources, timing, science and scheduling. And now the Alabama Supreme Court has made it more challenging for Alabamians to have an IVF baby in 2024 than it was for my parents in 1981. Science should move us forward, not backward.

At its core, IVF is a miracle of modern medicine and a fulfillment of unwavering hope. The events we’ve seen unfold in recent days, however, have been motivated by fear — fear of prosecution of clinics and doctors, and fear of what might happen if embryos are transported across state lines. I will continue to hold onto the hope that lawmakers in Alabama will take action to protect IVF treatments. The fact that Gov. Kay Ivey, a Republican, supports such an effort and has said that fostering “a culture of life” includes helping “couples hoping and praying to be parents who utilize IVF” echoes the optimism at the core of reproductive technologies.

As I navigate these uncertain times, I remain steadfast in my belief that the power of science, coupled with compassionate legislation, will pave the way for a future where the dreams of parenthood through IVF are safeguarded, cherished and celebrated.

This segment aired on March 1, 2024.