Advertisement

'Bad seed': Two generations, two terrible crimes

Resume

Not long after Jacob Wideman murdered his summer camp roommate, Eric Kane, in 1986 — seemingly with no motive — a question emerged in the breathless news coverage of the tragedy: Was Jake a “bad seed”?

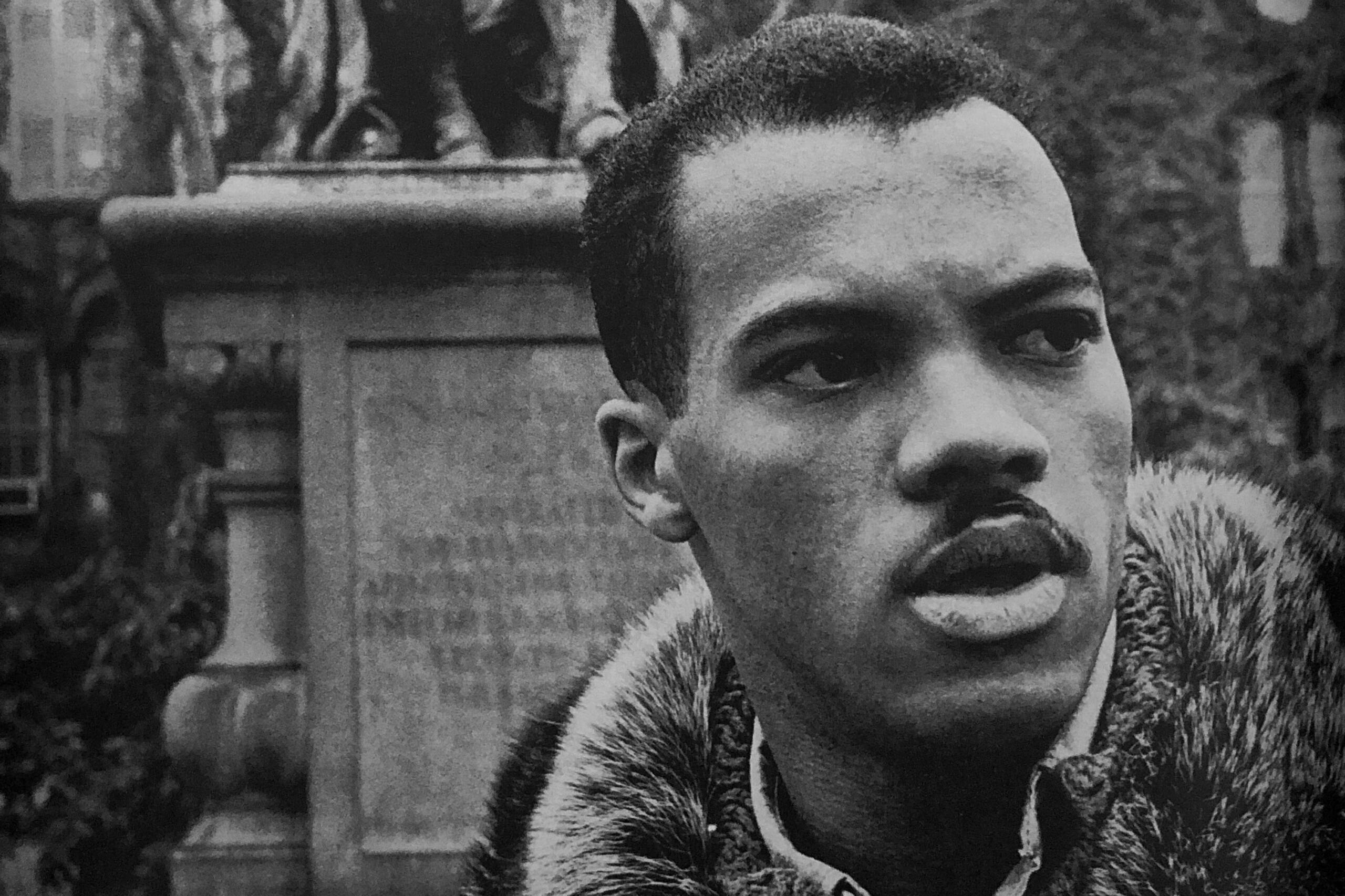

It was no accident that some reporters latched onto the phrase. After all, it was plucked straight from perhaps the most famous book written by Jake’s own father, acclaimed author John Edgar Wideman, about his family’s experience with violence, trauma and incarceration.

But John Wideman wasn’t writing about his son Jake when he used the phrase “bad seed” in his seminal memoir, “Brothers and Keepers.” The book was published in 1984, two years before Jake murdered Eric. Instead, John was writing about his own younger brother Robby, Jake’s uncle, who years earlier had participated in a robbery that went very wrong. A man died, and although Robby didn’t pull the trigger, he was sentenced to life in prison.

“The bad seed. The good seed. Mommy's been saying for as long as I can remember: ‘That Robby, he wakes up in the morning looking for the party,’” John Edgar Wideman writes in “Brothers and Keepers” — and reads aloud in this latest episode of Violation, a podcast series from The Marshall Project and WBUR. This idea from John’s book, of going “bad,” would be applied to Jake, too, although John was disdainful of the concept.

“Bad Seed,” Part 2 of Violation, tells the story of Jake’s Uncle Robby through interviews with John as well as with Jake, who remembers having epiphanies as a boy that he would somehow follow his uncle’s path. The episode also brings listeners through the harrowing weeks and months after the murder of Eric Kane, when Jake Wideman turned himself into authorities and began his long journey through the criminal justice system.

Ultimately, this episode asks: What should happen to kids like Jake?

Listen to new episodes each Wednesday, through the player at the top of the page, or wherever you get your podcasts. Violation will also be available on The Marshall Project's website and on Here & Now from NPR and WBUR.

Show notes:

Read the transcript:

"Bad seed"

Last week, on Violation:

ABC 15’s Dave Biscobing: In 1986, as a teen at summer camp, Jacob Wideman murdered fellow camper Eric Kane. As Eric slept, Wideman stabbed him twice in the chest. There was no motive, just murder.

Jake Wideman: I don't want anybody to feel sorry for me. I don't want anybody to, you know, take my side out of sympathy or say anything like, “Well, you know, he's been in since he was 16, and 36 years, and, oh, poor guy.”

Ted Bartimus: Sanford Kane lost his son to murder in 1986 and noted Black writer John Edgar Wideman lost his son Wednesday to life imprisonment for the same murder.

Beth Schwartzapfel: You see, by the time their son went away for murder, the Widemans were no strangers to American prisons and jails.

John Wideman: I heard the news first in a phone call from my mother. My youngest brother, Robby, and two of his friends had killed a man during a holdup.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Some people were already suggesting that violent crime ran in the family. John Wideman’s brother — Jake’s uncle Robby — was already serving a life sentence for murder.

[MUSIC]

John Wideman: You never know exactly when something begins.

Beth Schwartzapfel: This is John Edgar Wideman, Jake Wideman’s dad, reading from what is, perhaps, his most famous book.

John Wideman: When I tried to isolate the shape of your life from the rest of us. When I tried to retrace your steps and discover precisely where and when you started to go bad.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Here’s the thing. This book was published two years before Jake killed Eric Kane. This writing isn’t about Jake. It’s about Robby, John Wideman’s little brother.

But this idea of going bad, from John’s book would be applied to Jake, too.

Arizona Daily Sun reporter Ted Bartimus remembers the first time he heard about this book. It was in the room at the Flagstaff Police Department, where the town’s crime reporters would gather each day to find out the latest news.

Ted Bartimus: And one reporter was a radio reporter. She lay a book down. She goes, “I saw this in the bookstore.” And it was the book “Brothers and Keepers” by John Edgar Wideman. At that point, it became much more high profile.

Beth Schwartzapfel: “Brothers and Keepers” is a memoir, published in 1984, that toggles back and forth between the voice of John, a college professor and noted author. And the voice of Robby, his youngest brother, Pennsylvania prisoner number AP3468.

In the book’s opening passage, John describes hearing the news from his mother that Robby and his friends had committed a robbery that went very wrong. A man was dead and Robby was on the run.

John Wideman: Robby was a fugitive, wanted for armed robbery and murder. The police were hunting him and his crime had given the cops license to kill.

Beth Schwartzapfel: And now, Jake, Robby’s nephew, John’s son, was also on the run, also in connection with a murder – just two years after “Brothers and Keepers” had been heralded as an important book.

Maury Povich on “A Current Affair”: Hello, everyone. I'm Maury Povich. Welcome to “A Current Affair.” Our main story tonight is about the family of a respected author and academic Pulitzer Prize-winner John Wideman.

Beth Schwartzapfel: John Wideman did not win a Pulitzer. He did win the prestigious PEN/Faulkner Award, twice. That fact is fairly straightforward. Not all facts are. Truth can be slippery, and the heart untrustworthy – as John often explores in his work.

I first encountered “Brothers and Keepers” years ago, in grad school, where I was studying creative nonfiction. I was already covering criminal justice as a freelance reporter, and I was mesmerized by the way Robby, with all of his mistakes and missteps, becomes every bit as understandable and relatable as his brother John, who on paper did everything right, but in his heart felt he was as flawed and broken as his brother.

“Brothers and Keepers” tells the story of John using his smarts and his basketball skills as his ticket out of poverty, and Robby going another way. In the book, John quotes a Sly & the Family Stone song, “A Family Affair,” that seems to describe the two brothers precisely.

Lyrics from Fly & the Family Stone’s “A Family Affair”: One child grows up to be somebody that just loves to learn. And another child grows up to be somebody you’d just love to burn.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Robby hadn’t pulled the trigger in the robbery, but because of his involvement in the crime, he was still convicted of murder. Jake was only 6 when Robby was sent to prison for life. He grew up making annual trips with his family to Western Penitentiary in Pennsylvania to visit his uncle.

Jake Wideman: There were times when I was kind of, I had kind of epiphanies, I would call them now, when I was very young that my life was going to be very similar to my Uncle Robby's, that I would wind up in prison. I just felt this kinship with him.

Beth Schwartzapfel: There was one metaphor in particular that John examines in “Brothers and Keepers.” Was his brother Robby a “bad seed”?

John Wideman: The bad seed. The good seed. Mommy's been saying for as long as I can remember: That Robby, he wakes up in the morning looking for the party.

Beth Schwartzapfel: John says now he should have put scare quotes around the phrase “bad seed.” He was disdainful of the concept, and used it ironically. But that was lost in the breathless news coverage that came later – when his son Jake was the latest Wideman to be connected to a murder.

Maury Povich on “A Current Affair”: 16-year-old Jake Wideman, described as a bad seed and neglected child, doesn't know why he killed a fellow teenager in summer camp. Was it because he felt an inescapable bond with his uncle, a bad seed himself, who also became involved with murder? It is a mystery that has shaken this quiet community in Laramie, Wyoming.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Jake Wideman was raised with all the advantages his father and his Uncle Robby had not been, and yet here was an inexplicable crime, twice in two generations. Had something been passed down through the generations to Jake?

I’m Beth Schwartzapfel. From The Marshall Project and WBUR, this is Violation – a story about second chances, parole boards, and who pulls the levers of power in the justice system. This is part 2: “Bad Seed.”

[MUSIC]

In late August, 1986, no one knew where Jake was.

A week prior, 16-year-old Eric Kane had been discovered stabbed to death in an Arizona motel room. No one had heard from Jake Wideman, the boy he’d been rooming with, since the murder. The Oldsmobile they’d been driving with a group from their summer camp was also missing. With Eric dead and not a word from Jake, the minds of Jake’s parents, John and Judy, were spinning into every imaginable nightmare scenario.

John Wideman: I remember a few days after hearing you were missing and a boy found dead in the room the two of you had been sharing. I remember walking down towards the lake to be alone because I felt myself coming apart. The mask I've been wearing as much for myself as for the benefit of other people was beginning to splinter.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Jake's father who had already won acclaim with more than half a dozen books that grappled with racism, violence, and the criminal justice system. All of those issues had hit close to home for him already — but never quite this close. This passage is from an essay he wrote years later, reflecting on that terrible week.

John Wideman: I was afraid you were dying or already dead or suffering unspeakable tortures at the hands of a demon kidnapper.

Beth Schwartzapfel: A few days after Eric was murdered, the blue Oldsmobile was found abandoned near the bus station in Phoenix, about two hours south of Flagstaff. The campers’ belongings were untouched in the trunk: clothing, cameras, walkmen. But $70 in cash and some $3,000 worth of travelers checks that the counselor Bill Hammond had stashed under the driver’s seat were missing.

Ted Bartimus: Well, the kid was on the lam.

Beth Schwartzapfel: This is Ted Bartimus, the Arizona Daily Sun reporter

Ted Bartimus: They didn't know where he was at.

Beth Schwartzapfel: The missing travelers checks began turning up cashed at Greyhound bus terminals, motels, and airports in Los Angeles, Denver, Minneapolis and New York. Flagstaff police spoke to the clerk at one hotel on Long Island, and she described the person who checked in as Mr. Hammond as being in his early 20s, about 6 feet tall, and maybe Puerto Rican, judging from his complexion. He seemed to be suspicious and “up to something,” she said. For seven days Jake wandered aimlessly on buses and planes.

Jake Wideman: I took the bus to LA, and then I may have spent the night in LA. It's again, it's foggy.

Beth Schwartzapfel: He met a girl on a Greyhound who told him to come visit her outside Duluth, but when he arrived he discovered she lived in a group home for troubled teens and he was not allowed in.

Jake Wideman: My parents have said, my dad in particular, that as the week went on, it became more and more clear to them that it probably wasn't the case that I had been kidnapped. And then they didn't want to draw, of course, the logical conclusion.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Over the course of that week, the reality of what he had done had begun to sink in, Jake said, and by the time he found himself stranded in Minnesota with very little money and nowhere left to go, he realized it was time to call his family.

Jake Wideman: I think that both ends of the conversation, we were just kind of in a fugue state, I guess is the best way to explain it. Nobody really knew what to say other than to just figure out what I should do. I know they told me that they loved me and they were with me no matter what.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Seven days after Eric Kane was found murdered in Flagstaff, Jake arrived in Arizona and met his attorneys for the first time. His parents had frantically arranged to hire lawyers in Phoenix, knowing Jake would need them. Jake and his family stayed together in a hotel. They probably talked. They must have eaten. His brother Daniel said they may or may not have played a pickup game of basketball. But no one remembers any details about that night – it was all a blur.

Daniel Wideman: If anything, it was just, it's unbearable to sit here in the hotel room and stare at each other and what's familiar? Let's go shoot around; let’s go get out on the court and, you know, sweat a little.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Daniel and Jake and their sister Jamila all say basketball was always the thing that bound them together. Jamila later became a lawyer, but for years she played professionally in the WNBA. She said for the Widemans basketball was like going to church.

Jamila Wideman: I think basketball to my family has been like a language. It has almost been like a strand of our DNA.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Like a strand of their DNA. In college, John was captain of Penn’s basketball team and on the All-Ivy League team. I don’t know much about sports, but I know that as college basketball goes, he was a big deal. And he speaks about the sport with a kind of deep reverence, and irreverence. Like when you’re flying through the air going for a shot, and just for a moment, the world falls away and you don’t know what’s going to happen.

John Wideman: Reaching for a note, and gets there. It’s a dancer spinning. It's humping with your lover, whatever. In that moment where, you know, it's just, you're gone. But you're not gone. You're suddenly more alive than you're ever going to be in any other situation.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Basketball is just what the Widemans did, through good times — and bad. And this was a bad time.

Here’s Daniel at a parole board hearing years later, describing this day when Jake gave up running and arrived to meet his family in Arizona.

Daniel Wideman: I didn’t recognize my brother that day. He was devastated. He was, I, we actually slept in the same bed that night and he trembled and cried all night.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Jake may have been unrecognizable to his family that day, but this was not the first time they had reason for concern about his mental health. Jake says he spent his childhood wrestling with demons that his family couldn’t, or didn’t, understand, until it was too late.

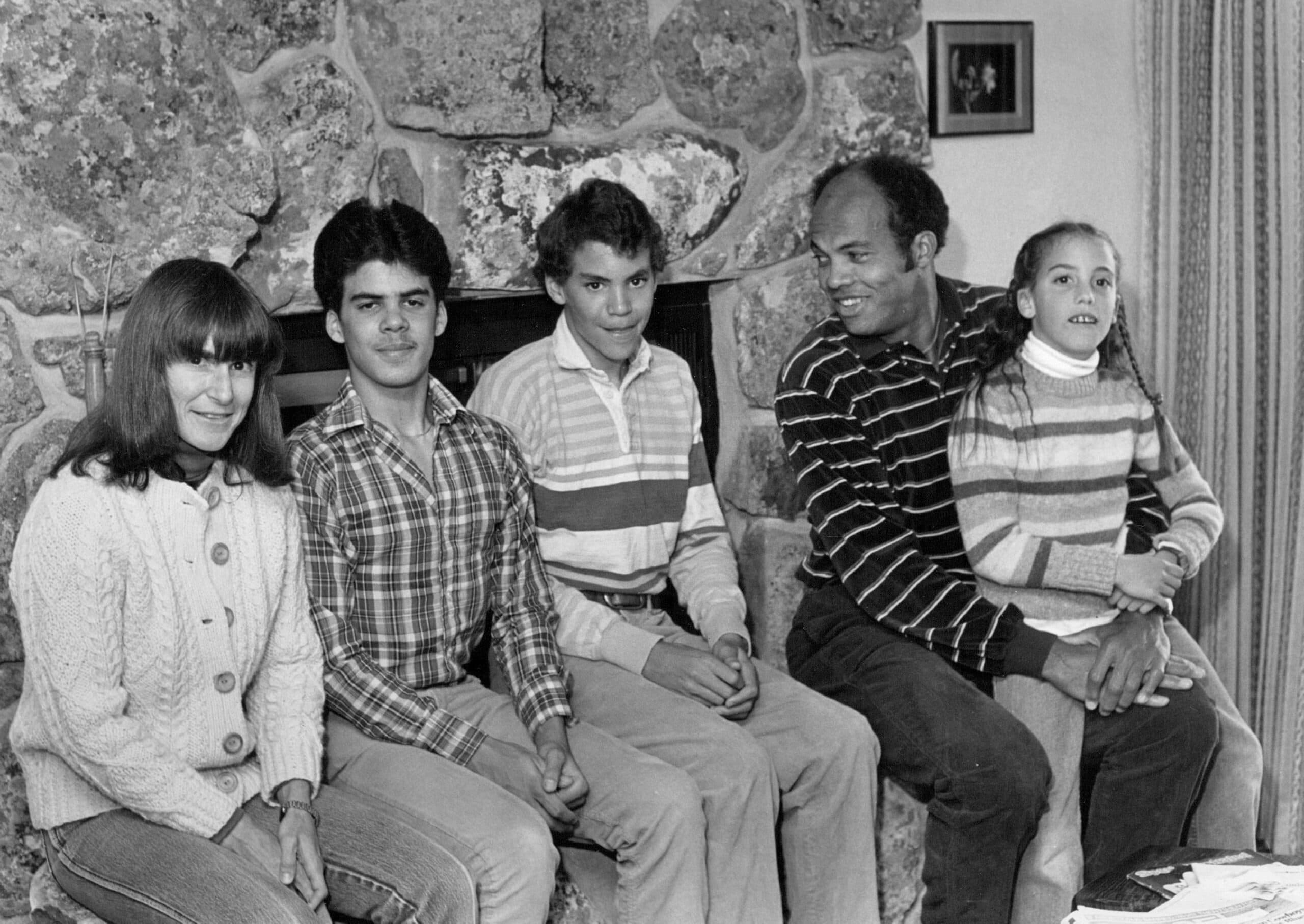

The Widemans lived in Laramie, Wyoming, where John taught at the University of Wyoming and Jake’s mother, Judy Wideman, had helped to found a progressive elementary school called the Laramie Open School. She later went on to attend law school at the University of Wyoming, motivated in part by the experience of John’s brother, Jake’s Uncle Robby, in the criminal justice system.

As far as Jake and his brother, Daniel, can remember, there weren’t many other Black kids in town. Their dad, John, was Black. Their mom, Judy, was white.

It wasn’t just that that set them apart. This is Daniel, Jake’s brother.

Daniel Wideman: My mom was definitely integral in exposing us to the world beyond, ensuring that we didn't get stuck in a Laramie mindset. She would drive us two and a half hours in the middle of the night to go to jazz concerts in Denver, you know, on a school night.

Beth Schwartzapfel: John and Judy Wideman divorced in 2000. And Judy has had some health problems the last few years. That’s why you’re not hearing from her in this story. But she’s always been an important presence in her kids’ lives.

One terrible event that dominated headlines around that time was the Atlanta child murders.

Newscaster: No where was there any mention of an investigation into possible Ku Klux Klan involvement in the murders. But nine months before …

Beth Schwartzapfel: 30 Black kids killed between 1979 and 1981. Judy made all her kids T-shirts that said, “I have a dream of life for Atlanta’s Black kids.”

Daniel Wideman: She just kind of made her own, made these shirts, and we wore them to school every day and she'd wash them every night, during that. So instilling that awareness and then that, it was normal to stand up and call out injustice at an early age.

Beth Schwartzapfel: I mean, how did you, how old were you when you were going to school in that shirt? And did other kids look at you like, what? Who is this kid? Like, what in the world?

Daniel Wideman: It was the worst time. It was middle school, you know, where it's conform or death.

Beth Schwartzapfel: In fact, the Wideman kids were just a little bit different everywhere they went. Though the phrase “code switching” didn’t become common until much later, that’s the experience Jake and Daniel describe about their childhood bouncing between visiting their mother’s family and their father’s.

Daniel Wideman: Being in Homewood versus being in, you know, a mansion in Princeton, New Jersey, where my mother's family lived. But I felt equally loved both places.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Homewood, the neglected Black neighborhood in Pittsburgh where John Wideman grew up, is the setting of several of his books. It’s a complicated place — a lot of poverty, drug use, and despair, but also a close-knit community of extended family and friends who look out for each other through it all. Their sister Jamila was a good bit younger than they were, but Jake and Daniel would often go with their cousins to the playground in their neighborhood.

Daniel Wideman: He would always get looks, you know, who's that kind of dirty-blond haired kid hanging out with Monique and Tameka, you know? As the lightest-skinned of all of us, you know, he would… I do remember like cousins sticking up for him. “No, that's our Jake.” He's not, you know. “He's with us. He's a part of this crew.”

Beth Schwartzapfel: But as much as he was a part of the crew, he struggled from a young age in a way that his brother and sister did not.

Between the ages of about 3 and 8, Jake would throw these enormous raging tantrums. His family had a name for them — “moose acts” — where he would throw things and break things and flail his tiny body inconsolably. His mother would sometimes have to pin him down to prevent him from hurting himself or someone else.

Jake Wideman: The way I would describe it now is a venting of things that I couldn't express, and things that I didn't know how to feel and I didn't know how to manage at that age.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Much later, as a teenager, there was the time Jake took the family car and disappeared, driving into Colorado and wrecking on a snowy road. His parents brought him for several sessions with a psychiatrist after that, concerned that this was a veiled suicide attempt. It was, Jake says now. After he crashed the car, he even went as far as to walk into the snowy woods with no coat on, hoping he might freeze to death.

But at the time, Jake told the psychiatrist it was simply an impulsive act after he’d been rejected by a girl. The psychiatrist concluded that Jake had some problems with impulse control and maturity, but that he was doing well overall and after a few therapy sessions, he was “back on track.”

Despite these warning signs, no one in Jake’s family could foresee what would happen just a few months later. Jake, alone, wandering the country with stolen traveler’s checks, his summer camp roommate murdered. It didn’t take long before he realized he would have to face up to what he had done.

Jake Wideman: There was no way that I could remain on the run indefinitely. I needed to figure out what I was going to do.

Beth Schwartzapfel: After a week on the run what Jake did was turn himself in. And that was the beginning of a long fight over what to do about a kid like Jake. A kid who did well in school, played varsity basketball, then one day did something unthinkable.

More in a minute.

[MUSIC]

Beth Schwartzapfel: On Aug. 21, 1986, Jake Wideman arrived at the Flagstaff Police Department with his parents and his attorneys and surrendered.

He was wearing a Princeton Day School jacket, a pair of Converse hi-tops, and a blue cap. Flagstaff Police Det. Frank Manson notes that he asked one of Jake’s attorneys, “If there was some simple or logical explanation for Jacob’s disappearance which might show his innocence and eliminate the defendant as a suspect so that the investigation might continue in other areas.” Jake’s attorney told Det. Manson that “no explanation would be offered.”

Patty Garin: We had lots of theories about what had happened in his brain at that time and what was what caused it. And the doctors who evaluated him had various theories. …

Beth Schwartzapfel: This is another one of his attorneys from that time, Patty Garin.

Patty Garin: But because Jake just wasn't able to talk about anything. I mean, he was a 16 year old. He just wasn't able to talk with any insight about what his life had been like as a child and growing up, because everybody thought he had a very normal life and in many respects he had a very normal, wonderful life.

Beth Schwartzapfel: The day after Jake surrendered, a judge said there wasn’t enough evidence to keep him in jail, for now. There was little more than circumstantial proof that Jake had killed Eric. It seemed completely out of character. There was no obvious motive. And Jake wasn’t talking. So the judge released Jake to the custody of his parents.

In the midst of all of this, the family was in the process of moving from Laramie, Wyoming, to Amherst, Massachusetts, where John had landed a new teaching job.

In Massachusetts, they had Jake admitted to a psychiatric hospital, which, according to Jake and his attorneys, was wary of having a kid charged with murder at their facility. This was more than 30 years ago and juvenile records are sealed, so I’m relying on the memories of Jake and his attorney, as well as court transcripts and documents that describe the events. But according to them, Jake and a bunch of kids at the hospital were roughhousing one day. He tackled or wrestled with another kid while playing ball. And the staff, already on high alert, called the police.

Patty Garin: So I first met Jake in the juvenile holding dock cell in Boston juvenile court to get arraigned on an assault and battery charge.

Beth Schwartzapfel: This is his longtime attorney, Patty Garin, again.

Patty Garin: And I went into his cell and he was curled up in a ball on the floor, hugging his knees, crying. And that's how we met.

Beth Schwartzapfel: For decades, Eric Kane’s family and friends have insisted this incident at the psych hospital was attempted murder — that Jake was trying to strangle this kid. But both Jake and Patty — and the police officer who investigated the incident — say that’s just not what happened.

Patty Garin: A very nice Boston police officer came and testified that he didn't think anything happened other than the hospital didn't want him there. And the judge dismissed the charges.

Beth Schwartzapfel: It's important to remember that when Jake first turned himself in to the police, he didn’t confess to the murder. He didn’t plead guilty. It was just the beginning of a long legal fight. This happens all the time.

But, after Jake had been admitted to the psychiatric hospital in Boston, he did something that shocked his family and his legal team. Something that changed the trajectory of his case, and his life.

Ted Bartimus recalls how one day in September, not even a month after the crime, Flagstaff Police Det. Mike Cicchinelli got a call.

Ted Bartimus: Basically, the kid spilled his guts to Det. Cicchinelli, I think his name was. I'd hate to have been Jacob's lawyer.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Jake, who had not yet turned 17, told Cicchinelli to turn on a tape recorder. He wanted to make a statement. “I murdered Eric Kane,” Jake said. It was the first time he had said this out loud to anyone except his lawyers. “I deeply, deeply regret what happened,” Jake said, according to the transcript. “I want you to understand that and I want everybody to understand that.”

This call was recorded on a reel-to-reel dictatape, which I guess was state of the art at the time but no one within a hundred of miles of Flagstaff has the capacity to play it in 2023. I tried. Here’s what the tape sounded like in a news segment — apparently even 30 years ago it sounded awful because they have an actor doing a voice-over:

A clip of an actor reading Jake Wideman’s confession on “A Current Affair”: It was not premeditated. It was a result of a lot of buildup, of a lot of different emotions. I never thought about it. I just woke up and didn't know what I was doing. I wasn't thinking straight.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Jake’s family — and his lawyers — had no idea he was going to confess to the police. And when Jake made that phone call, he made his lawyers’ jobs a lot harder. The judge ordered Jake held in a juvenile detention facility in Arizona.

Patty Garin says the legal team’s initial goal was to keep him in the juvenile system, where he could get treatment instead of punishment. Though Jake had not been diagnosed with a mental illness at this point, it was clear something was very wrong. But if he had been tried as a juvenile, the state would have had to release him at age 18 — way too short a time, in the judge’s view, to protect society from Jake, and Jake from himself. So six months after the murder, the judge decided Jake would be tried as an adult, and he was arraigned and transferred to the county jail.

Now that it was no longer a question who killed Eric Kane. Eric’s parents turned their grief and rage on Jake — they wanted the state to pursue the death penalty, even though Jake was only 16. The Kanes also turned their rage on someone else: Jake’s father, John.

Ted Bartimus: I'd never experienced such hatred on the part of… these people hated John Edgar Wideman and the kid, you know, it was like he was something from the devil, the way that they talked.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Ted Bartimus interviewed Sandy and Louise Kane several times in the years that followed.

Ted Bartimus: They would go on and on about, you know, how much they hated, you know, Wide— John Edgar Wideman and how he created this, this son that was a murderer.

Beth Schwartzapfel: It’s hard to say why the Kanes focused their rage so squarely on John. Jake had two parents. I’ve never heard them talk this way about Judy.

One thing that seemed to especially enrage Sandy Kane was a letter John sent about a year after the murder.

“Dear Mr. Kane,” the letter began. “Almost a year has passed since you lost your son. It becomes clearer and clearer to me that I have lost mine. Eric is irretrievable; Jake is still alive, but suffers in ways I hope no one else will be forced to experience. Grief is not measurable. Each person’s portion is a full portion.”

He went on to say he forgave the Kanes for pursuing the death penalty against Jake. Yes — he forgave them. “Your need to see my son dead is part of what I’ve been struggling with,” he wrote.

The one thing he never says is, “I’m sorry.”

John Wideman: I was naive, I think. Because it was still too fresh, still. I remember the letter and I remember the response. Their response was basically, “Fuck you.” So it wasn't a very politic letter and it may have been offensive.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Was your letter in earnest? I mean, was it from the heart? Can you explain kind of where you were coming from?

John Wideman: I don’t remember the letter. I was totally devastated, in my way. In the same way, the victim's family was devastated. I was trying to do something, talk to people. And I was — also had selfish motives, I'm sure. I was hoping to get maybe a bit of mercy from the victim's family because I knew they had the power to help my son. And I thought I could call on that, evoke that, evoke some sympathy or some mercy. I think I only infuriated the family.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Sandy Kane spoke about this letter at Jake’s sentencing hearing in 1988. “Only a man without regard to anyone's feelings, including his son, could have the utter gall to forgive me for my wish to rid society of the monster he gave it,” he told the judge.

We don’t have a recording of this hearing, so we’re reading from the transcript.

Actor reading Sandy Kane: There's another father in this tragedy for whom I feel no bond; merely hatred, instead. That's John Wideman, Jacob's father. I stop at him when I look for reasons to Jacob's acts. Animals bear their young, and often end their tie at that point. Human parents treat their children as a precious gift, spending the time and efforts to bring them up. From infancy, it's clear that Jacob Wideman was crying out for help. All of the evidence says that he was ignored. He can't comprehend that he created a monster who clearly is the cause of Eric's death.

Beth Schwartzapfel: At one point, Louise Kane told an Esquire reporter that “Jacob Wideman was brought up to believe that it isn’t wrong to take someone’s life.” When the reporter, Chip Brown, asked her how she knew that, she responded, “because it says so in John Wideman’s books.”

I thought a lot about that. Having read many of Wideman’s books, I tried to grapple with where she might be getting that from. I mean, many of these books are dark, no doubt. The books he had already written by then included a beheading, a group of Black men who plan to lynch a white police officer. A recurring murder fantasy that may or may not have taken place in a bathroom. But he did not write these books for the sake of being shocking or grisly. He was trying to understand the humanity at the heart of all that rage and anger and pain, to see how racism deforms everything it touches.

When I asked John Wideman what would make the criminal justice system more effective and humane, that’s what he came back to.

John Wideman: The only possibility is for individuals to feel about others the way they feel about themselves. To really make the jump out of this one skin and see another person both as you, and not you.

Beth Schwartzapfel: If you do that, then that obliges you to see things from, you know, the victim’s family’s point of view, too, who are saying, “He should never get out.” Right? “He shouldn't even try to get out because these parole board hearings are so painful for us.”

John Wideman: Yeah, I can understand that. I can understand. And maybe if I was looking at a young man, I knew that he stabbed my son to death, I might hate that person forever. I might want to see him burn in hell. I might want to get a knife in my hand and kill him. All right. Fair enough. But is that all I would feel? Is that all I would feel? All I can say is I hope not.

Beth Schwartzapfel: John didn’t say what else he thought the Kanes should feel. But one of the cornerstones of his writing is that even the most broken and imperfect people are still human. In fact, their brokenness is part of what makes them human. Robby, he wrote, was “first a man, then a man who had done wrong.”

That’s why the idea of a “bad seed” — with scare quotes — is so nonsensical, in John’s mind. Whether we’re talking about his brother Robby or his son Jake or anyone else.

The Kanes of course…seem to feel differently.

I have tried for years and in many different ways to speak to the Kanes, or a friend or relative on their behalf – to learn what they feel. But since I haven’t been able to do that, here is Eric’s mother, Louise Kane, recalling the time after Eric was killed at a parole board hearing.

Louise Kane: For days, and weeks, and months, and a year, I couldn’t stop crying. All day. I couldn’t eat. I couldn’t sleep. I felt that my entire insides had been ripped out without the benefit of anesthesia.

Beth Schwartzapfel: She goes on: I did some of my best crying in the shower, where the sound of the water masked my sobs and washed away the tears, and my shaking body wouldn’t scare my family.

Louise Kane: I smelled Eric’s clothes. I wore his sweaters and jackets, sleeves rolled up. One day I realized I had not cried the entire day, and I cried because I thought maybe I was losing Eric.

Beth Schwartzapfel: By 1988, Jake’s case had been set for trial and rescheduled multiple times as prosecutors and Jake’s attorneys fought over everything — whether the case belonged in adult court at all. Whether his confession was admissible. What punishment he’d face if he were convicted.

Maybe, if Jake was a scared and broken kid, then he deserved another chance. But if he was a bad seed — if there was some essential thing about him that was violent and wrong — then he would always be a danger.

The Kanes had pushed prosecutors to pursue the death penalty. As Louise Kane told the judge in Jake’s case, “The only way we can be sure that this animal will not strike again is to execute him. The dead neither break out of prison, nor get paroled.”

Patty Garin: We were obviously trying hard to get them to drop the death penalty because if Jake was going to go to trial, then they were insisting that he'd face the death penalty. That didn't work.

Beth Schwartzapfel: This is Jake’s longtime attorney, Patty Garin, again.

Patty Garin: So they were always holding the death penalty over him to try to force a plea to say, if you plead, then you won’t get executed. But if you go to trial, you'll get executed. When you say that to a 16 year old enough times, guess what? They're going to take a plea.

Beth Schwartzapfel: In 1988, Jake Wideman pleaded guilty to first-degree murder, plus additional theft charges for the travelers checks and the car. The Widemans and the Kanes were all in the courtroom for his sentencing, burdened with grief.

“Not a day has passed that I have not wished with all of my heart that there was something I could do to take back my actions,” Jake said in a statement. “I wish there was something I could say to the Kane family to express my feelings, but when it comes down to it, sorry seems kind of weak and kind of empty to me, and undoubtedly to them, as well … I feel helpless in the face of the destruction I have caused, and hate myself for it.”

The Kanes’ statements were equal parts tender remembrances of Eric and vitriol against Jake and John. “Where is death? Who can tell me?” Eric’s mother said. “Who can help me find my child?”

They recalled Eric’s love of science and art and reading, his voracious curiosity. They called Jake subhuman and a vicious animal.

According to the terms of the deal, the judge sentenced Jake to 25 years to life. At the urging of the Kanes, he made a recommendation to whatever parole board would hear his case 25 years in the future that Jake never be paroled.

And then the judge said this: “Let the memory of Eric be like a bouquet in your living room every morning, and please don't let it die because of your hatred. This is the end. Let it be the end. Glorify the memory of your son with good memories.”

Some families of murder victims eventually do, somehow, find a way to forgive the person who took the life of their loved one. Maybe their faith helps them get there. Maybe another family member committed a terrible crime and it helped them see the perpetrator as human. It’s not uncommon for families to experience both sides of that kind of violence.

But of course, not every victim forgives. The shape of each person’s heartbreak is unique to that person’s heart. I can’t know what’s in their hearts, but it certainly seems like the Kanes have not forgiven.

“Bad seed” or not, Jake was also still grappling with something – something it would take decades to figure out. And, many years later, when Jake Wideman began appearing before the parole board, he not only had to face the parole board members who would determine his fate, he also had to face the Kanes again. And the Kanes would push the boundaries of the way parole normally works.

Sandy Kane: But as opposed to what some have asserted, I am neither an angry nor a vengeful man. I’m instead asking you to force him to stay where he is in order to prevent another father from feeling my pain and loss at his hands.

Next time, on Violation.

If you want more information about Jake’s case, additional documents, photos, and related stories, head over to themarshallproject.org/violation, and, wbur.org/violation.

Violation is a production of WBUR in Boston and The Marshall Project.

Editing of the show comes from Geraldine Sealey, who is also managing editor of The Marshall Project, and Ben Brock Johnson, executive producer of WBUR Podcasts. Additional editing, project management and web production from Amy Gorel. Quincy Walters is our producer. Mix, sound design and original music composition by Paul Vaitkus. Fact checking help from Kate Gallagher at The Marshall Project. Illustrations for our project come from Diego Mallo.

I’m Beth Schwartzapfel, your reporter and host. I’ll talk to you next week.