Advertisement

Commentary

Shall we dance? How the cha-cha helped my marriage

It’s Friday night and my husband Jeff and I are in a suburban Connecticut dance studio, learning the cha-cha with 12 other adults. Della Reese is singing “Why Don’t You Do Right?” over the sound system while our teacher counts out, “One, two, cha-cha-cha.”

When my older son told us he was getting married, I made the plea for dance lessons. To support my petition, I did plenty of research. When I typed “benefits of ballroom dance” into the search bar on my web browser, Google automatically added “for seniors.” The list was long — cardiovascular health, improved balance, greater strength. There were even claims that ballroom dancing would turn back the clock.

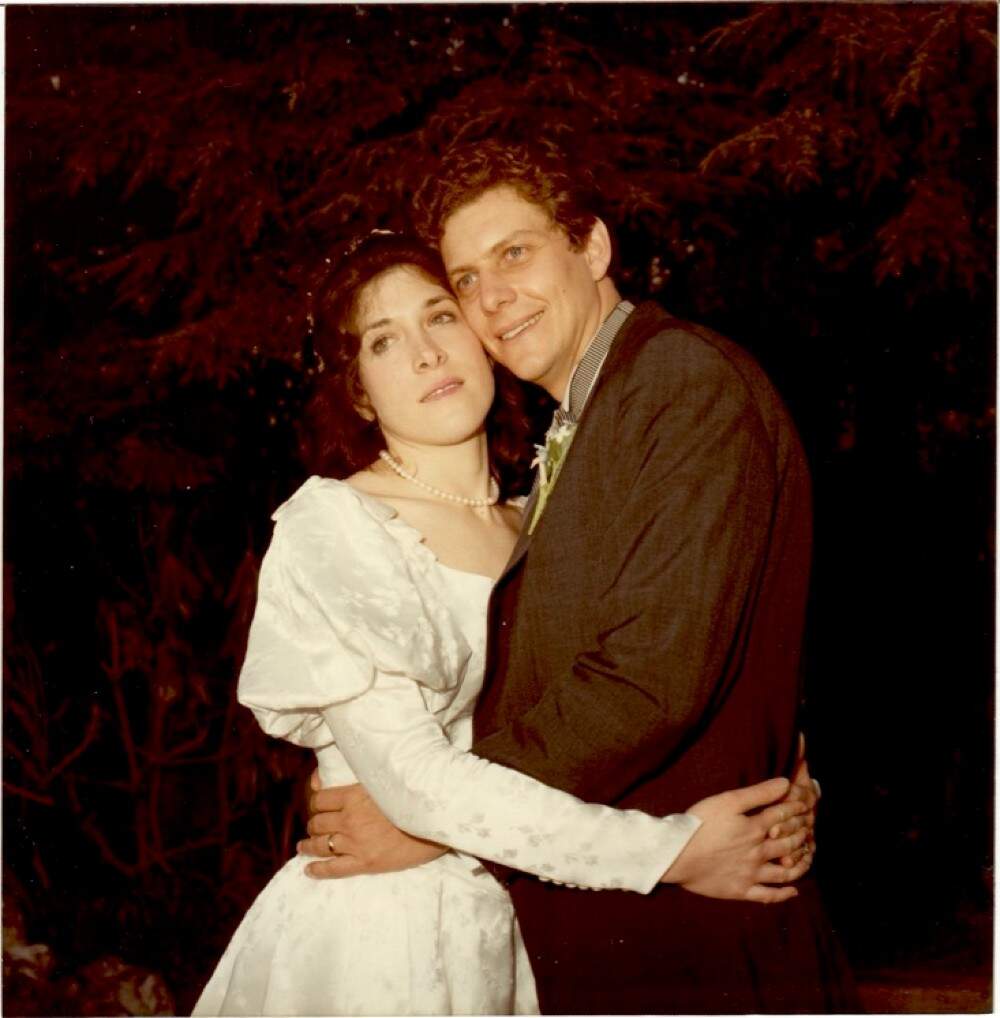

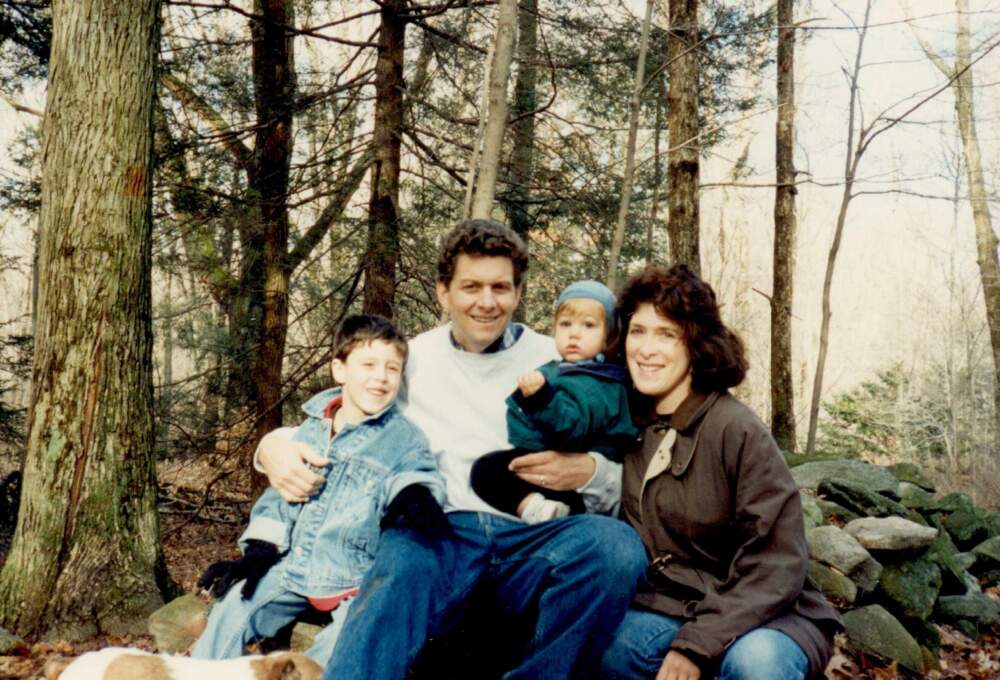

I told Jeff I wanted to do better than the bear hug sway we did at our own wedding, but I had another reason I didn’t share. With our sons grown and with more time to spend together — just the two of us — we were becoming snippy with each other and persnickety about tiny housekeeping details.

“That’s not the way I would’ve wiped the kitchen counters,” are words I have heard myself say.

We needed something fun and new to share.

Jeff and I never participated in the disco scene and the only line dance we remember is the Hokey Pokey. As we drove to our first lesson, Jeff said, “You know, I think we looked great at our wedding.” If I hadn’t been so aggravated by his speedy driving, I might have leaned over to kiss him.

Our teacher, Michael, who founded the studio and directs it along with his wife, refers to us as boys and girls even though many of us are old enough to be retired. On another night, when Michael and a younger dancer teach West Coast Swing, a newer dance that doesn’t have a history of gender stereotypes, he calls us “leaders” and “followers,” based on dance positions instead of gender.

Tonight, though, he’s saying boys and girls. Michael begins by demonstrating how the boys should initiate a spin. “It’s hard to be us,” Michael tells the room. Everyone nods in agreement.

For the followers’ part, Michael emphasizes that we should take a step directly toward our partner. He lifts his arm in a subtle movement — “That’s all the sign you get, girls.” This is the acknowledgment it’s hard to be us — the followers — reading the leader’s cues while still doing our own steps.

I’ve come to understand it’s not easy to be a leader or a follower.

“It’s hard to be us,” Michael tells the room. Everyone nods in agreement.

A couple of months into our lessons, we noticed we were experiencing some of the health benefits of learning a new physical skill. But what I hadn’t counted on was the clock turning back emotionally. As I process the proximity to my ever-changing dance partners (we rotate every minute or so), I feel nervous anticipation and am suddenly very in touch with my 13-year-old self.

In the year-long humiliation that was eighth grade, I found joy in square dancing lessons in the gym. We made fun of it — so square, the anti-rock and roll — but there was also giddy excitement in cavorting through a line of stomping, sweating adolescents. Now I feel a similar thrill when I raise my arms in the air and twirl around with sashaying, hesitant adults.

Unlike the square dancing lessons of eighth grade, these ballroom dance lessons after 40 years of marriage seem to be working. But I’m not only learning how to dance, I’m understanding how hard it is to be “them.” Not just the men, but everyone around me. No matter how old we are, the discomfort of learning to do basic dance steps with strangers is one way to become a kinder person. Especially to your spouse.

Advertisement

At some point in every lesson, Michael says, “Cover for your partner.” He’s talking about more than apologizing when missteps occur. He’s telling us to take into account individual dance-related strengths and weaknesses, and reminding us to be gracious with one another.

Even if Jeff and I started the lesson harried and out-of-sync, I’m glad when our turn to dance with each other comes around. In our allotted minute together, we hold each other tight. We still stumble through the steps, but notice that we fit in each other’s arms in a way that we don’t with the other students. It’s easy to get frustrated, but because ballroom dancing is new to both of us, and we are equal in our lack of ability, the frustration easily turns to laughter when we try to practice what we learned at home. In those moments, perhaps we realize that cleaning a kitchen counter a certain way is unimportant, that micromanaging how someone feeds a parking ticket into a meter is unnecessary.

At the end of class Michael stops the music to recap what we learned. “Now on the count of three, give your partners one big clap.”

We all clap once and head to the chairs to put on our street shoes. We grab our coats, our bags and our car keys. On the way home, I resist the urge to point out the yellow light as we approach it. Without prompting, Jeff slows down and stops. We are quiet, connected momentarily by the knowledge of what it means to be us and the feeling of relief that we made it through another class.