Advertisement

Field Guide To Boston

How blue is Massachusetts? What to know about politics and voting

If we asked an AI-powered bot to conjure up images that reflect Massachusetts politics, it might spit back a sepia-toned scene of smiling Kennedys helming a sailboat. Or maybe it would pull an archive photo of a fiery James Curley or amiable Tip O'Neill. But that's the past.

The biggest stars of Massachusetts politics today (search #mapoli, you'll thank us later) do preserve some of the state's reputation as a small place with big political influence. But there's more to politics and policy around here than the greater and lesser Kennedys, pithy one-liners ("All politics is local," "He did it for a friend") and a penchant for press coverage. (And, admittedly, not always for good behavior.)

If you're prudent — or if you're new in town — you'll likely want some political SparkNotes in a state where people like love to mouth off about positioning and policy.

We'll help parse what's mythical and what's real around the state's progressive reputation, explain why some mayors wield big power while others don't, and even let you in on how New England town meetings are both democracy at its simplest and protocol at its most opaque. Plus, as practical people ourselves, we'll tell you how to register to vote and figure out how to follow the money that lands in politicians' war chests.

How towns and cities govern

There are 351 cities and towns in the Bay State, and there are several ways that each structure their local governments.

For now, let’s focus on how Boston is governed.

A Boston built on compromise: How its mayor and council serve constituents

Chief of the city, the mayor is basically the CEO of Boston. The mayor appoints the police commissioner, members of the development authority, signs roughly 20,000 municipal paychecks and — unlike all other Massachusetts cities — even decides who sits on the school committee.

But Boston mayors aren’t all-powerful; they can’t make laws without approval from the city council (and certain powers, like taxation and rent control, are reined in by the State House). Still, mayors often set much of the city's direction.

Boston’s longest-serving mayor, the late Tom Menino, is remembered for ushering in a massive development boom across the city. His successor, Marty Walsh, took on climate resiliency and housing construction efforts. Michelle Wu’s administration so far has prioritized housing and environmental policies.

Keeping tabs on the Boston City Council's agenda is a solid way to understand the big debates shaping the future of the city. (Local politics superfans can follow the council on YouTube and turn on notifications to never miss a meeting.)

Boston has 13 councilors: four at-large members who represent the whole city and nine district councilors, each repping about 75,000 Bostonians. The council approves the mayor’s budget, and in 2021, voters decided to give the body the power to amend the budget and reallocate funds.

The city council also has the power to hold hearings on hot-button issues and can send city ordinances (i.e. local laws) to the mayor’s desk. They can override a mayor’s veto if nine councilors band together.

All 13 seats are up for grabs every two years.

As is the case for many major cities, the council also can be a stepping stone to higher office. If you look at who sat on the council back in 2021, you’ll see a who’s-who of progressive Massachusetts politics: U.S. Rep. Ayanna Pressley, Massachusetts Attorney General Andrea Campbell, state Sen. Lydia Edwards and Mayor Michelle Wu.

The way Boston political consultant Doug Chavez sees it, a councilor is a resident’s liaison to city government.

“I always tell people: call your local city councilors, and call one of your at-large — all four if necessary — so they can help guide you through this,” Chavez said. Councilors often take up a range of issues, from broken street lights and potholes to fielding complaints about city investments.

You can figure out who your councilor is here.

For non-emergency needs, you also can call Boston 311, a 24-hour hotline that promises to connect you with a constituent service representative for requests like graffiti removal, pothole fixes and needle cleanups. There's an app where you can file reports, too, if you’re not a big phone talker.

Advertisement

Governments outside Boston

Boston's mayor-council system isn’t the only way cities and towns in Massachusetts set up their municipal governments.

Cambridge has a “council/manager” system, in which the council appoints one of their own to serve as a mayor to handle ceremonial duties and head both the city council and school committee. The city manager, meanwhile, is hired by the council to serve as CEO. Worcester uses a similar system.

(Fun fact: Cantabrigians, as well as residents of Amherst and Easthampton, use a form of ranked-choice voting, which is an arguably more democratic but somewhat complicated process. Massachusetts voters in 2020 rejected a ballot effort to adopt ranked-choice voting in statewide elections.)

Most towns in the state use the “town meeting” form of government — a vestige of old Yankee direct democracy — where voters are empowered to make the big decisions on budgets and bylaws.

Here are some fast facts about town meeting governments:

- There are two types of town meeting communities: under “open town meetings,” every registered voter can participate; under “representative town meetings,” voters select representatives. (Brookline, for example, elects 255 town meeting members.)

- Across the state, more than 260 communities hold “open town meetings,” while about 50 use the representative variety. (Thanks to the Mass. Municipal Association for this breakdown of how these meetings work.)

- Alexis de Tocqueville, the French chronicler of 19th century U.S., thought New England democracy was the bee’s knees: “The native of New England is attached to his township because it is independent and free: his cooperation in its affairs ensures his attachment to its interest; the wellbeing it affords him secures his affection; and its welfare is the aim of his ambition and of his future exertions.”

Massachusetts politicos

The executive branch

The state is run by a governor and a lieutenant governor who are elected on the same ticket. There are four other statewide elected positions: treasurer, secretary of the commonwealth, auditor and attorney general.

As of 2023, all but one of the six positions are held by women, including Gov. Maura Healey, the first openly gay woman elected as an American governor. The lone man in statewide office is Bill Galvin, who with his election to an eighth term in 2022, is Massachusetts’ longest-serving secretary of state.

There's also an eight-member Governor's Council, elected in districts across the state, which presides over matters like pardons, governmental appointments or judicial picks put forth by the governor.

The Legislature

Let's now talk about the glowing hearth of statewide politicking: Beacon Hill.

Beacon Hill, the name for the area where the State House sits, is hard to miss. It's a landmark in the state capital with the giant golden dome that overlooks Boston Common. There's no governor’s mansion in Massachusetts, so the governor works at the State House alongside the bicameral Legislature's 200 members: 40 senators and 160 representatives.

Lawmakers meet from January through the end of July, which you can consider crunch time at the capitol.

“The Legislature historically saves most of the substantial bills until the very end of formal sessions,” said Steve Brown, a veteran political reporter at WBUR. “That leaves very little time to publicly debate the merits of those bills.”

In a single year, Brown also said lawmakers typically take up just one or two omnibus bills, which are legislation that knits together various smaller policy measures.

“They’ll say we want to do health care bills this year, then education next year,” he said. “That tends to be the way they do things.”

The state has a greater share of Democratic-leaning voters than any other state — except Vermont — in the country, and that’s reflected on Beacon Hill. Only about 15% of state lawmakers in 2023 identify as Republicans, with about two dozen GOP members in the House of Representatives and just three Senate Republicans.

As the late Roxbury-born writer Nat Hentoff put it: “In Boston, the political season began and ended with the Democratic primaries.” Hentoff was writing about the mid-20th century, and not much has changed since.

Not that there aren’t exceptions, like the 2010 U.S. Senate race to replace Ted Kennedy. As Brown recalled: “The conventional wisdom was that the winner of the Democratic primary would be the odds-on favorite to win the seat, but the conventional wisdom was turned on its ear.”

Republican Scott Brown beat Martha Coakley to win the senate seat that, two years later in 2012, he would lose to Elizabeth Warren.

But the 2010 race was an exception. The state has only sent two Republicans to the U.S. House since 1975. And in the 2022 congressional elections, nine of nine incumbents held onto their seats. Each one, you might’ve guessed, is a Democrat.

Is Massachusetts a left-wing bastion?

People moving to the Boston area might be put off — or gratified — by the state's progressive reputation. But while champions of the left like Warren and Pressley make headlines promoting progressive policies nationally, they don't reflect the range of views held by the pols running the state.

So, how progressive is Massachusetts really?

Massachusetts is one of the most urbanized places in the U.S., and its residents are among the most educated. Analysts often point to those facts as big reasons why Democrats enjoy broad support at the polls. But scratch past that coat of blue paint, and you’ll find undertones of purple and red.

Yes, Joe Biden earned twice as many votes here as Donald Trump in 2020; but more than a million Massachusetts voters chose Trump. Yes, Democrats outnumber Republicans 3-to-1 in voter registration; but the majority of the state’s 4.9 million registered voters are “unenrolled,” meaning they don’t formally associate with any party. And yes, Massachusetts has voted for the Democrat in every presidential election since Ronald Raegan in 1984; but it’s been run by Republican governors for 24 of the 39 years since.

OK, but how does Massachusetts measure up on progressive policy?

On civil rights, Massachusetts has been a national pioneer in advancing reproductive rights and expanding health care, and in 2004, the state became the first in the nation to allow same-sex marriage.

But socioeconomic measures show a different side of the state.

“There have been many progressive policies that have been implemented to good effect,” said Michael Goodman, an economist at UMass Dartmouth. “But I think fundamentally, are we a progressive state in terms of outcomes? No.”

Take housing. Consumer Reports ranks Massachusetts as the second-worst state in the country for renters when factoring cost, apartment availability and tenant security. Voters made rent control illegal in 1994 and the Legislature appears unlikely to change that. That makes Massachusetts an outlier among the nation’s bluest states, such as New York, New Jersey and California, all of which have forms of rent control.

Homeownership rates reveal another shortcoming, according to Goodman. The state ranks among those with the greatest income inequality. Why? Because most people accumulate wealth by owning a home, he said, and that has become increasingly out of reach for many.

“If you look at it through the lens of [inequality], the outcomes in the state certainly are not well-aligned with what you would think a progressive society would be aiming towards,” Goodman said.

And consider the racial homeownership gap. In no small part due to redlining and blockbusting practices enacted decades ago, Massachusetts is in the middle of states when it comes to the Black homeownership rate: 36% of Black families own, compared to 70% of white families.

Analysts on opposite sides of the aisle — Paul Craney, spokesman for the conservative Massachusetts Fiscal Alliance, and left-leaning political strategist Doug Chavez — draw similar conclusions on the progressive question.

“A lot of areas are mostly white, working-class folks, and often they’re not as liberal as people think,” said Chavez.

Craney agreed, saying, “If you remove the partisanship, Massachusetts is not as liberal as some would think.”

Still, Goodman and Schuster highlighted several areas where Massachusetts has seen policy shifts to the left:

- The steady increase in the minimum wage.

- The pre-Obamacare health care extension.

- Paid sick leave and insured family and medical leave.

There’s also been some movement toward a more progressive income tax structure in Massachusetts. The Fair Share Amendment, or so-called “millionaires’ tax,” added a second tax bracket for income above $1 million. It was adopted after a 2022 ballot initiative and is expected to hit 0.6% of taxpayers.

Pollster Steve Koczela, head of MassINC Polling Group, has a different take. He said the state does live up to its progressive reputation — at least in terms of the views of most residents. However, "voters often choose candidates that are more moderate than their own views," Koczela said.

Koczela pointed to several polls that suggest the state is "to the left of nearly every state on key national issues where we can make a comparison."

- Massachusetts had the highest support for abortion rights of any state.

- The Bay State and Vermont had the highest vaccination rates in the country, and vaccine views were found to be closely tied to political views.

- Massachusetts and Vermont also gave Biden the highest percentage of votes in 2020.

A changing GOP

Until recently, the GOP in Massachusetts fit squarely in the increasingly quaint idea of the Northeast Republican, politicians generally considered more moderate than the current Republican Party writ large.

There was a long stretch in which Republican governors ran Massachusetts. And they all fit that Northeast Republican mold, starting with Bill Weld in 1991, through successors Paul Cellucci, Jane Swift and Mitt Romney, whose final term ended in 2007. Then there was a Democratic interlude with Deval Patrick before Republican Charlie Baker ran the state for two terms. These GOP leaders won their elections with support from a small but mighty band of Republican voters in central Massachusetts, and another cluster between Boston and Cape Cod.

Beyond their strong presence in the gubernatorial big chair, moderate Republicans in Massachusetts have had some success at the local and federal level, from Richard Tisei in the Massachusetts Senate to Edward Brooke and Scott Brown in the U.S. Senate.

Policy-wise, these Republicans were often cited as "fiscally conservative and socially liberal," with a focus on tax and pocketbook issues. That dichotomy also extended to some Democrats in the state, notably U.S. Rep. Paul Tsongas.

But wait, we said "until recently" above. What's changed? In recent years, the state GOP has seen a surge of fiscal and social conservatives, who excoriated the Baker-types as poor standard-bearers for the Republican message. That movement accelerated during President Trump's term in office.

The inter-party disagreement is still very much alive, as the Massachusetts GOP continues its soul-searching after a 2022 election cycle filled with strife and significant financial issues.

Civic duty

Now you have a foundation for understanding some basic points about Massachusetts politics. But no political guide is complete without a breakdown of ways to roll up your sleeves and get involved.

Voter registration

Registering to vote is the first item to check off your to-do list. You must register 10 days before a preliminary or general election. There are several ways to land on the official voter rolls in Massachusetts. You can register:

- Online.

- By mail.

- In-person: this you can do at your local town or city hall, or at one of the secretary of state's offices.

- Registration also happens automatically when you apply for a driver’s license, learner’s permit or state ID at the Registry of Motor Vehicles; or when applying for health coverage through state portals. (You can opt out, of course.)

- People incarcerated for felonies cannot vote until they are released.

The secretary of state's office has more on the voter registration process. If you’re not sure about your voter status, it’s easy to check: just enter your name, birthday and zip code right here. The state’s website will also show your polling place and your local elected officials.

What to know before hitting the polls

This isn’t a state that has a voter ID law, but poll officials may ask you to prove your identity in certain situations:

- If you are voting for the first time in Massachusetts in a federal election.

- If you are an inactive voter.

- If you are casting a provisional or challenged ballot.

- If the poll worker has a reasonable suspicion that leads them to request identification.

Should it come to that, valid forms of ID include driver’s licenses, a utility bill or any other document that shows your name and address. Worst-case scenario, you will be allowed to vote with a provisional ballot. That means you’ll get to vote, but your ballot will only be counted if officials later confirm you’re correctly registered.

How to vote by mail

There’s also the option to mail in your ballot. You can get an application to vote by mail here. Applications must be received five business days ahead of an election, but election officials recommend you send in your ballot at least two weeks beforehand.

How can you return your ballot? You can mail it inside the provided envelope or hand-deliver it to your local election office or early-voting location. (Many communities also put out ballot dropboxes.)

You cannot, however, drop your ballot off at a polling place on Election Day. You can use the state’s ballot tracker to be sure your vote was accepted.

Research candidates

If you want to learn more about the candidates and their campaigns, journalists often tout this advice: follow the money.

It can help you understand more about who’s running if you look at what people and groups fund their campaigns. To examine a politicians’ financial support, you can review legally-required filings with the Office of Campaign and Political Finance or poke around the ever-useful OpenSecrets.org, a nonprofit tracking money in politics.

Get involved

Thomas "Tip" O'Neill, the local kid who rose to become Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, is credited with popularizing the phrase, "All politics is local." And there sure are lots of ways residents can get involved in politics. Local GOP committees or Democratic town and ward committees welcome new volunteers.

And if you aren't a fan of picking between the political equivalent of Coke or Pepsi, there are plenty of other choices on the menu: The Libertarians are a recognized party in Massachusetts, and there are more than two dozen other "political designations" you could enroll with.

If you're really eager to get into the fray, you could run for office. The state requires candidates for local elections to file by the last Tuesday in May. For federal and statewide offices, the deadline for party candidates is the first Tuesday in June, while non-party candidates can dawdle until the last Tuesday in August. Check out the requirements here.

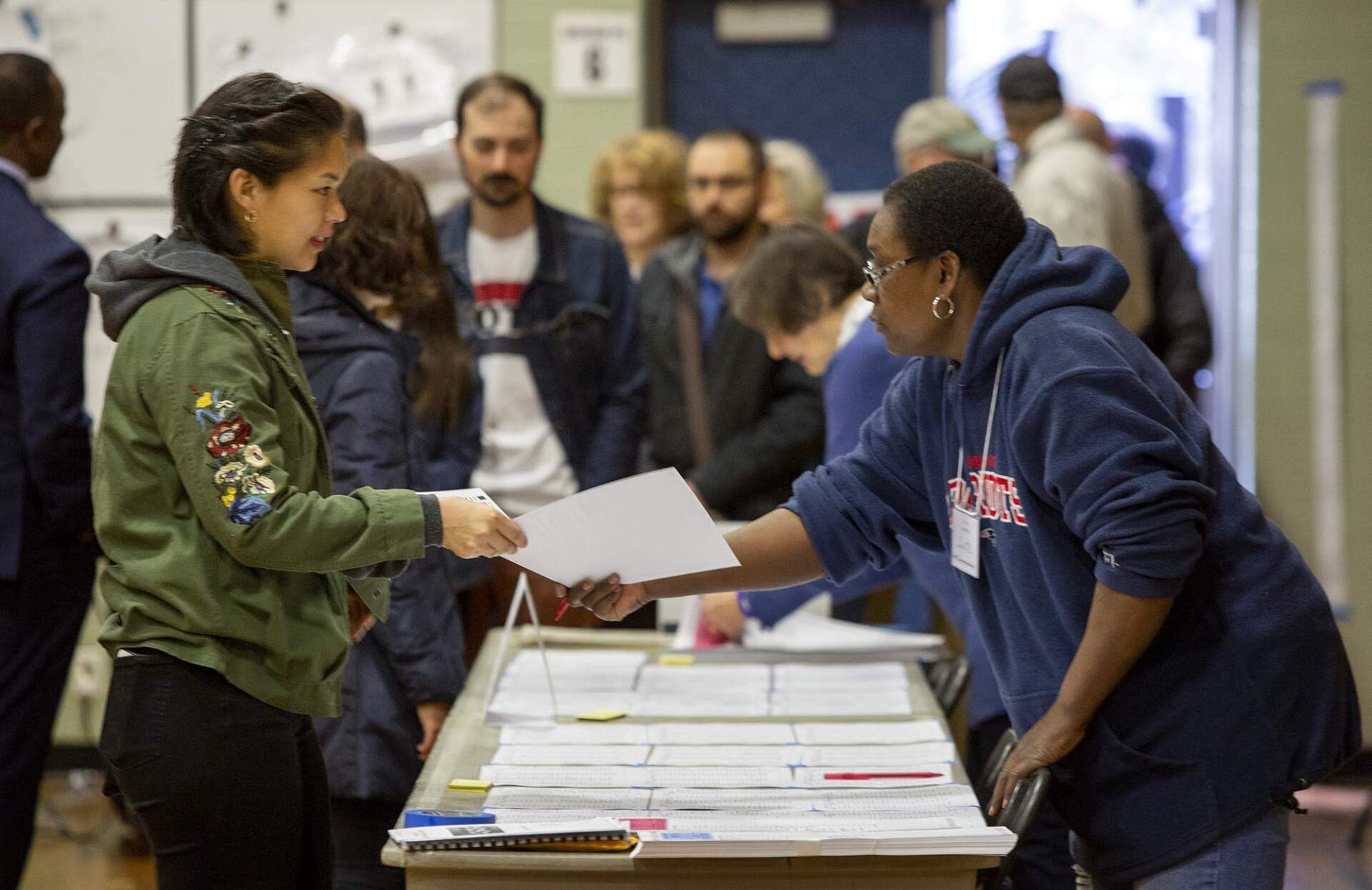

If you want to help get out the vote on Election Day, election leaders are always seeking poll workers. It arguably doesn’t pay a lot — in Boston you get $160 to $200 a day — but it comes with the satisfaction of bolstering democracy and meeting neighbors doing the same.

During a recent Boston election, Dennis Kirkpatrick, of West Roxbury, said his work at the polls over the last 15 years is all about the camaraderie — that and the free pizza.

And, of course, it's also about helping voters. One time, Kirkpatrick said he handed a ballot to a man who had moved to Boston from abroad. After casting his ballot, the man shook hands with each poll worker.

“And we said, ‘We do this all time,’ " Kirkpatrick recalled. "And he said, ‘You don’t understand. In my nation, we can’t do this. This is the first time I have ever voted.' "

With additional reporting from WBUR's Lisa Creamer, Nik DeCosta-Klipa and Roberto Scalese

This article was originally published on September 07, 2023.