Advertisement

Boston launches project reimagining who is memorialized

Resume

Cemeteries are some of Roberto Mighty’s favorite places. To ponder, to walk, to learn about. As the producer and host of the PBS show “World’s Greatest Cemeteries,” he uncovers deeper meanings beneath these places of final rest, and asks questions such as how many people are actually buried in the North End’s Copp’s Hill Burying Ground.

“It's important to keep in mind that most likely the headstones that you see now, are, shall we say, supplementing the many, many, many bodies that you don't see,” Mighty said.

Those forgotten to time are the ones Mighty cares about most. Researchers believe this cemetery holds the remains of at least 1,000 Africans and African Americans. They were stevedores, shopkeepers, and sailors. Also thought to be interred in this vast unmarked grave is the country’s first published African-American poet, Phyllis Wheatley.

“Well, so often — like where we are literally sitting right now — my people have in many cases gone unmemorialized,” he said. “To me, being unmemorialized is tantamount to being erased.”

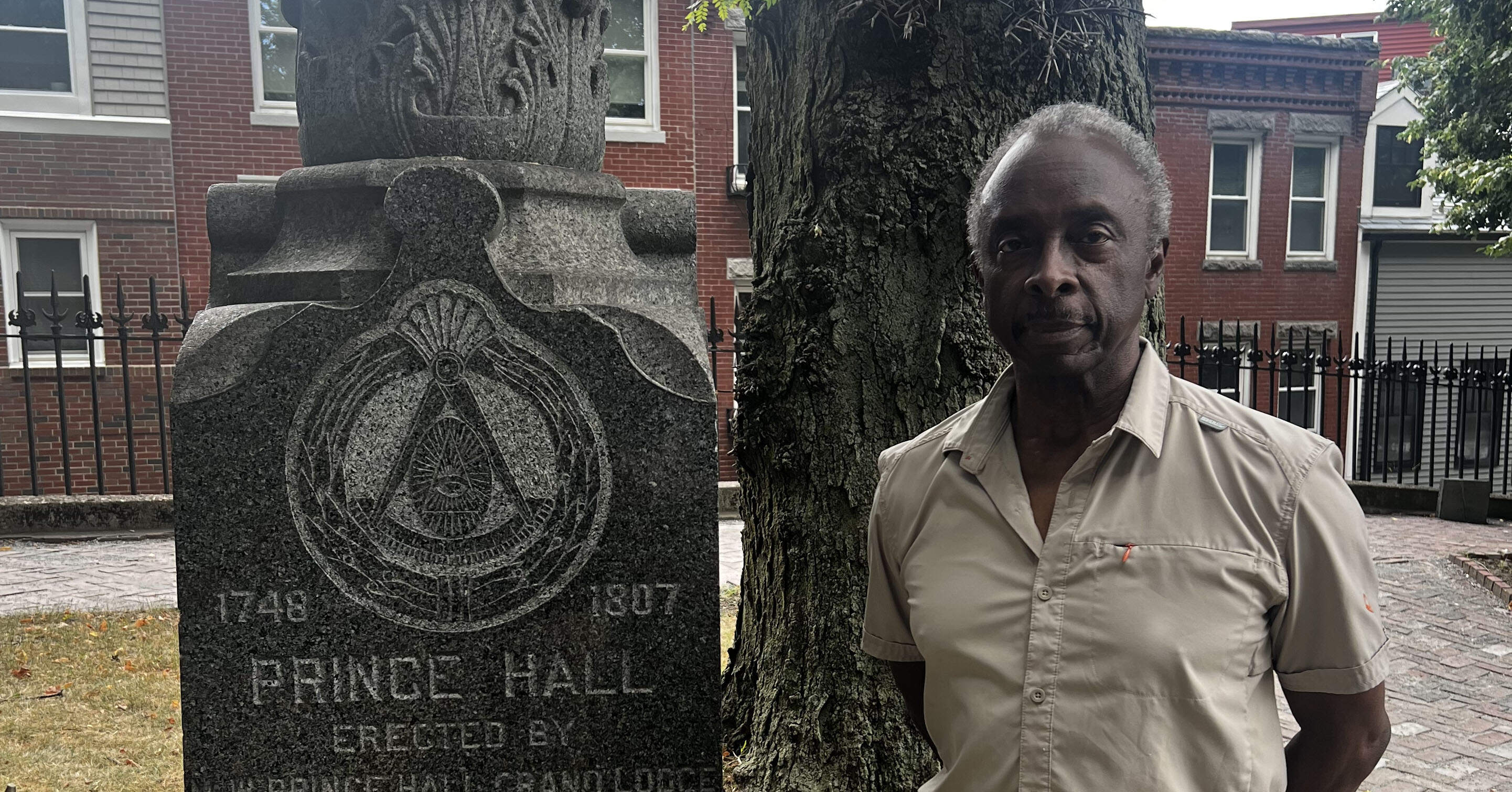

Worn slate headstones sit in rows and hail back from as far as the 16th century. Just a handful of them include names of prominent black leaders of the time, such as abolitionist Prince Hall. He founded the first lodge of Black Freemasonry.

Monuments in Boston are evolving as the city asks big questions about who is honored and memorialized. A $3 million multi-year grant from the Mellon Foundation is supporting this change, and the contributions of more than 50 artists who are experimenting with monumental ideas that include theater, murals, music, and community conversation. The new city program is called Un-monument | Re-monument | De-monument. Mayor Michelle Wu celebrated this investment alongside artists and city leadership at Massachusetts College of Art and Design earlier this month.

“Good art speaks to our time, and transformational art puts the past in conversation with the present, creating space for new dialogue and new ideas that deepen our connections to the people and places around us,” Wu said. “And in moments, in spaces, in different communities, catching it with that glint of inspiration, it cracks open the door to a brighter future for each one of us in our own way.”

Among the more than 30 projects to be funded is Roberto Mighty’s called “We Were Here Too.” Its aim is to resurrect the memory of those who lived in a historic black community that once existed in the North End known as “New Guinea.” Visitors will use QR codes as they enter the cemetery and find videos, court documents, images and poetry. Whenever he walks into a cemetery, he looks for the outsiders.

“I have to say that a big part of this is detective work,” Mighty said. “My work is built upon the work of historians who spend their whole lives studying these different sites.”

This effort is also a union of people who have been engaged in this work for many, many years, said Boston’s Director of Public Art Karin Goodfellow.

“In recent years, we have seen an acceleration of change and possibility in our monumental landscape where we didn't think it was possible before,” she said. “But it always was possible. It was always possible to tell the stories we strive to tell today. It is not too late to celebrate them and reject the concept of a static history.”

Curatorial partners were brought together from all across the city to commission temporary monuments in unique ways. Funding will include research and development grants so artists can prepare proposals for the next round of monuments planned for display in 2025. Organization will host conversations that interrogate issues such as reimaging safety in Chinatown at the Pao Arts Center, or questions of violence and rediscovery, according to Barry Gaither, director of the National Center of Afro-American Artists.

“We would like to say we will help people learn to love themselves because that is the best cure for violence, which is itself another form of the colonial impact of slavery and oppression to learn to hate yourself and not value your contribution,” Gaither said.

Advertisement

Artist Erin Genia served as a member of the “Un-monument” advisory board. She also previously served as an artist-in-residence in the city of Boston at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. It was around that time the city declared racism a public health emergency. As part of her time with the Office of Emergency Management, Genia organized a series of panels called, “Confronting Colonial Myths in Boston's Public Space” examining the city’s monuments.

“Art is a powerful place of discourse, where we can have difficult conversations, and where we can collectively honor the role of the creative process in creating equity and community change,” Genia said. “When I look back on the monuments that were built in past centuries, the values held by those in power at the time speak loudly. I see the erasure of Native American and Indigenous peoples and the celebration of settler colonialism. Our society has evolved to a greater understanding of why those things should not be memorialized.”

To me, being unmemorialized is tantamount to being erased.

Roberto Mighty

And it's the artists, she said, that are leading the way. One neighborhood at a time.

“That's how we're really taking the idea of ‘monument or unmonument,'” said Cynthia Woo, director of the Pao Arts Center. “How can the community come together to better the neighborhood and also preserve ‘Chinatown as Chinatown,’ as a cultural asset in this city. If we think about the whole neighborhood as a monument that does need to be protected, between gentrification, displacement, development, and increasing prices. How can we do that through unexpected ways?”

The program’s projects include temporary sculptural installations, murals, new media and theater. A large Mayan pyramid that speaks to the contributions of immigrants is in the works, along with live painting by graffiti artists and pieces about the Indigenous experience. President Jean-Luc Pierite of the North American Indian Center co-curated several public arts works.

“What we're looking for right now is definitely opportunities to memorialize the Indigenous perspective of the past few centuries, but also give our communities the opportunity to imagine themselves projected into the future,” Pierite said.

These monuments will not necessarily be permanent, they aren’t meant to be the final story. They are new touchstones, reframing the narrative to include a wide diversity of experiences. Roberto Mighty’s parents instilled in him a love of history. His Panamanian father and African-American mother gave him an understanding of his place in it.

“If little black children don't know that there were black people here when Paul Revere and John Hancock and John Adams and Abigail Adams were here, that they actually worked with them as part of the community,” Mighty said. “Then how are they to understand that they are important? So that's my mission here, to just remind us that these people existed.”

As family lore goes, Mighty’s parents fell in love in a cemetery. Surrounded by trees and headstones, they read poetry to each other. As a boy, Mighty thought the word “cemetery” was a place people went to read poetry. Now thanks to his project, it will be.