Advertisement

Commentary

Men want to have deep conversations: How I got the guys in my life to talk

Once when I was about 13, I was sitting on a beach with my cousin talking, and my Uncle Mike walked up. My uncle’s this sort of cheeky guy, and he said with a smirk, “So, what are you two talking about, the meaning of life?” My cousin and I laughed, but later I got to thinking, wait a second, what is the meaning of life? And is this something that people actually talk about?

Everyone knows it’s hard to get guys talking. But as a young man with a head full of ideas, I wanted more. As soon as my brain woke up in my teenage years, I wanted to talk about life, death, God, art. I was always in search of the Big Conversation. I grew up with my mom, dad and two brothers. My mom was usually up for hearing me out patiently as I went on about, say, the symbolism in Don McLean’s “American Pie.” With my dad and brothers, I hardly got anywhere.

Then, as now, the main way to get guys talking was to discuss sports. Was Wade Boggs the best hitter in baseball? Who was better, Magic or Larry? These conversations could fill entire car trips. Sports conversations, it should be noted, are also a coded way for guys to discuss some of life’s larger questions: how to deal with pressure; when to complain and when to keep quiet; what’s just and unjust; the importance of hard work. Sports talk wasn’t exactly “the meaning of life,” but growing up going to an all-boys school in a house with two brothers, it was the best thing on offer.

The first book I remember loving was “Zen And The Art of Motorcycle Maintenance.” When I read that book, it hit me: If I couldn’t have the Big Conversation with the bros, I could have it by reading, even if it was just between me and the words on the page.

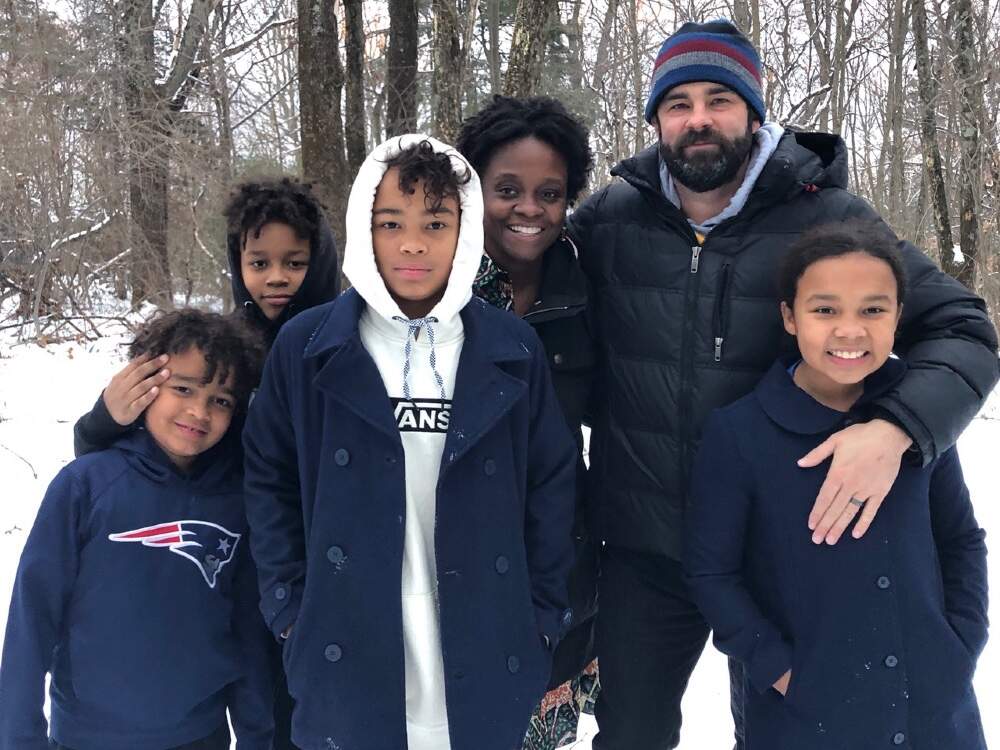

Flash forward a few decades, and now I have three sons of my own, as well as a wonderful daughter. I always figured as a dad I’d be different, and I’d regularly make time for talking about life’s mysteries and hardships, about films and politics.

Well, not so fast. As it turns out, I can hardly get my three boys to open up about any topic. As it was for me growing up, sports is the only failsafe. If I ask my boys who’ll be the top pick in the next NBA draft, I can pour myself another cup of coffee. (It’s the same with my daughter, by the way. But with her, I just have to open a debate about which is the best Taylor Swift album).

If I ask my boys who’ll be the top pick in the next NBA draft, I can pour myself another cup of coffee.

My oldest son, Henry, who is 16, is particularly tricky. He’s always been a quiet kid, and since he became a teenager, he’s a grown yet more inward—at least around me. He does really well in school, and talks a lot with his friends, but as for his dad, well, I can spend an hour in the car with him and not trade a word. Headphones are usually on. A solid “yup” or “nope” accounts for about 80% of his answers. Just typical teenager stuff as far as I can tell.

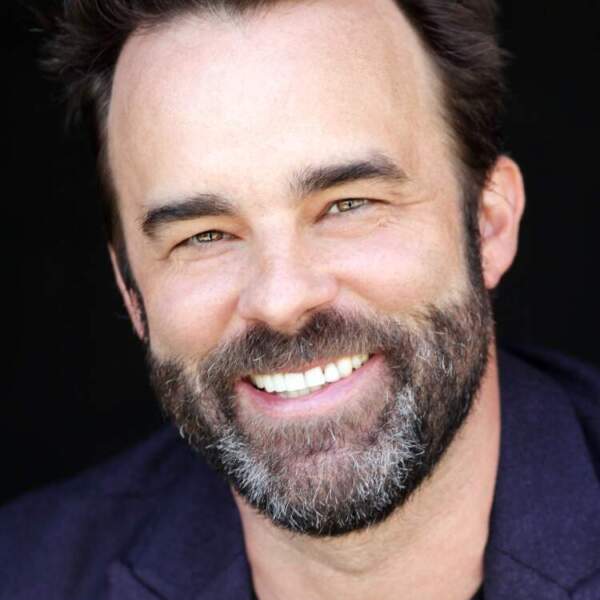

My quest for the big questions of life led me first to a love of reading, then to a love of writing, and more recently, a budding career as a novelist. This spring, I published my first novel, “Bunyan and Henry; or, the Beautiful Destiny.” It began years ago as a bedtime story for my four mixed-race kids, about a positive and unexpected partnership between white lumberjack Bunyan and Black steel drivin’ man John Henry. The final, grown-up version of the novel takes on a lot of the big topics I care about: racism, class, the history of indigenous conquest, capitalism and environmental blight. It also includes more personal subjects like destiny, friendship, and, yes, the meaning of life. When I secured a publishing deal, I thought, now I’ll get to dig into these topics with strangers far and wide.

Advertisement

Funny thing: it actually brought me right back to my family.

My father, brother and his father-in-law started taking online classes together during the pandemic as a way to stay in touch, and three months before the book published, my brother approached me with an idea: what about doing a course on my book? I drew up a syllabus and included an essay by J.R.R. Tolkien, an interview with Joseph Campbell and a reading from the Epic of Gilgamesh. From the very first Zoom, I could see something magical was starting to happen. My father was talking about the afterlife. My brother was talking about my book’s symbolism. My brother’s father-in-law was talking about what he thinks about Native American religion. Thirty years after my uncle joked, “What are you talking about, the meaning of life?” here I was, doing just that, with the guys in my life — the adult ones anyway.

At my book launch in March, just as I was wrapping up audience questions, a final surprise speaker stepped up to the stage. It was my oldest son, Henry. My quiet child of “yups” and “nopes,” walked right up on stage in front of room full of strangers and took the mic.

“Recently my basketball coach met with me and explained that in order to be successful we have to love the process as much as the result,” Henry began. “At first, I thought nothing of it. But as I started to think more, I realized that these words reflect my dad’s journey as an author.”

This was already a month’s worth of sentences.

My boy went on, “For a while, my dad was unlucky with agents and editors, and this was a time he was being tested. He had to embrace his love for the process, as much as for the end goal. Watching my dad take all of these hits and get right back up showed me how to take on life.”

Safe to say by this point, my jaw was on the floor.

“We came here tonight to celebrate his book, along with the path he’s taken to get here. How he never gave up on his dreams, and turned his goal into a reality. I’m happy to be standing here on this stage with you tonight, Dad. Thank you for everything. And I love you.”

In the signing line, some people asked me how I held it together on stage during Henry’s speech. I think I was just in shock. The emotion of it didn’t really hit me till a day later, when I was driving to another reading. Thinking back on the night before, the tears finally came. When I got where I was going, I parked the car and wrote Henry a long text that ended, “I’ve never been more proud of you as a father. I’ll never forget what you said for the rest of my life.”

He wrote back about an hour later, quick and to the point.

“I gotchu Dad.”

Turns out, some Big Conversations don’t need that many words.