Advertisement

BUSING'S LEGACY IN BOSTON, 50 YEARS LATER

Essay: The empty promise of ‘diversity’

During the time of Brown v. Board of Education, the most radical motives for desegregation were as much economic as cultural. Racial integration, theoretically, would disrupt the historical hoarding of power, wealth and resources by white people and schools.

In practice, however, desegregation efforts took on a racist spin that today’s school diversity work has inherited. They tried to claim that the resources of Black communities were lesser, that there was superior value in white schools and that Black youth would thrive in proximity to white students. Today, officials deploy a plethora of efforts that do little to disrupt racialized power and resource balance, but instead focus on checking the diversity box.

Boston has openly grappled with racial inequities in its schools for decades. There are promising pockets of racial equity work, and activists have remained vigilant. But Boston Public Schools yield unequal schooling on nearly every student outcome they measure. Black, Latinx and other youth of color consistently have higher dropout rates, lower graduation rates, and less access to advanced courses than their white and sometimes their Asian peers.

In Massachusetts, the school districts with the most students of color are consistently the most inequitably funded. Even so, the ever-present conversations about the racial achievement gap do not yield resource distribution — they yield diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) programming. It is a broken record, a parlance resonant of the era of school desegregation fruition after Brown v. Board. While disparities between Black and white students fueled the push for desegregation, these efforts did not ultimately change the power structures that would spare Black and people of color students from being devalued and hamstrung within a rigged game.

In Boston, one such DEI program is the often lauded Metropolitan Council for Education Opportunity (METCO). It functions as a lottery system that sends students from Boston, a school system where approximately 85% of students are people of color, to learn in the local suburbs where schools are overwhelmingly white and high resourced.

The Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education characterizes METCO as “a voluntary program intended to expand educational opportunities, increase diversity and reduce racial isolation.”

I’m cautious with these claims. Personally, as a Latina immigrant who was classified as an English language learner in school, I know what it feels like to be classified as a minority in educational spaces. Many of my own students at Wellesley College benefited from programs that — as METCO does for Boston children — selected them from a sea of peers in their low-income and POC communities to attend the prestigious private college. These same students tell me they often feel alone and guilty for being able to come to Wellesley when their peers did not have the same opportunity. They say they never feel completely at home in the historically white institution, and by the end of their studies, they question if they had access to the same learning opportunities as their white and wealthy peers.

METCO students have much higher graduation rates and college enrollment rates than students who remain in Boston Public Schools — but at a cost. Students report a lack of belonging and, ironically to the program’s goals, a type of racial isolation where they feel minoritized in a predominantly white environment. They also report understandable frustration over long commutes for a quality education. METCO recognizes this, and individual suburbs have instituted Family Friends Programs, which assign METCO students a family in their new school districts. This family serves as a touch point for the commuting student, and the programs frame themselves as cultural exchanges. But the exchange will always be one-directional.

Advertisement

The demand that students of color integrate into white spaces and norms does not just take an emotional toll. Behind the veil of every racially and socioeconomically diverse school, the rot of racism lingers. In diverse and desegregated K-12 schools, for example, higher tracked classes like AP, honors and gifted programs are still treated as the property of white students. School suspensions target Black and POC students the most. The racial inequities in these suburban schools do not get nearly as much press as those in Boston — after all, these schools are seen as “saving” students of color.

This is not what the architects of METCO had in mind. They were Black mothers, educators, activists and the Boston NAACP. It was a labor of anti-racist love.

METCO and DEI programs like it can be life altering for individual students who manage to benefit from them, but they are mere beginnings to massive systemic reform, not the endgame.

For a new generation of people who commit themselves to a future of racial and economic justice, there are questions they must ask themselves: Why do DEI and opportunity programs pick just a handful of young people to experience high-resourced schooling rather than invest more in their neighborhood schools? Is it true that the best education can only happen outside their communities? Why is it OK for those white, more affluent communities and schools to call themselves integrated without actually having Black, Latinx and low-income people living there in meaningful roles? If the goal of today’s diversity work, from conception to application, is to transform a racist status quo and to provide quality education for Black, people of color and low-income youth, then why are these efforts carried out at the expense of those same young people?

We must ask ourselves: Who actually benefits from diversity efforts?

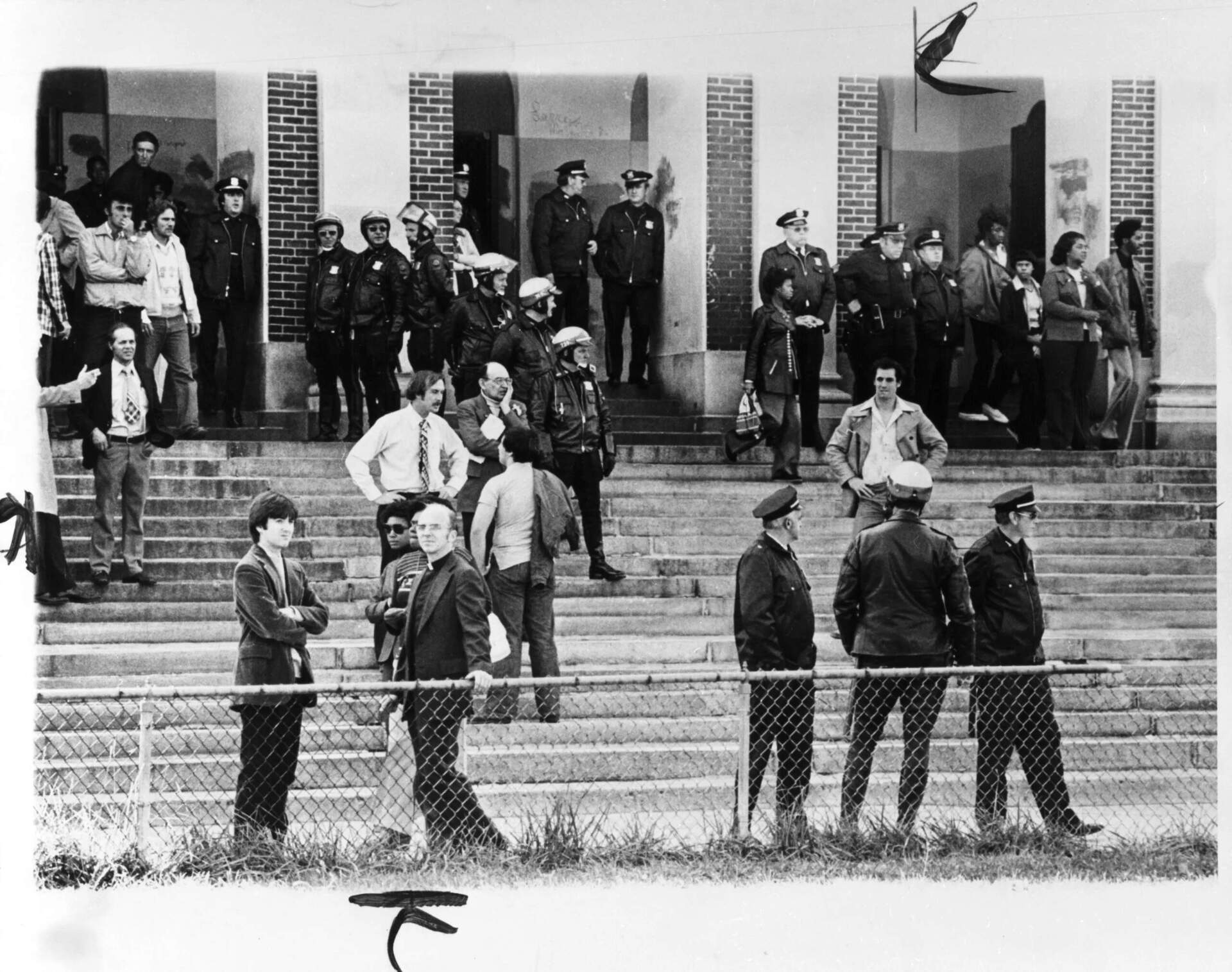

Mandated desegregation, like busing in Boston following the Morgan v. Hennigan ruling in 1974, set in motion an ugly period of white rage, anti-Black racist riots and mass exodus of white students refusing to integrate. Today’s more voluntary diversity efforts find greater acceptance, but are overly preoccupied with wanting to appear progressive and not wanting to anger white folks. These priorities harbor a stealthy kind of racism, the type that perpetuates an unequal status quo through the weak charity of DEI.

If they are meant to be anti-racist, diversity efforts cannot prioritize the racial comfort of white communities. In doing so, they engage in a performative type of progress. Instead, for racial and socioeconomic justice to happen, we must meaningfully challenge the hoarding of resources and opportunities.

Thank you to Wellesley College Knapp Social Science Center fellows Estefania Vasquez (2025) and Noely Irineu Silva (2027) for providing research support for this article.

This story was originally published by The Emancipator and is part of an editorial partnership between WBUR and The Emancipator on the 50th anniversary of a federal judge’s ruling that led to busing of schoolchildren in Boston.