Advertisement

Episode 8: 'Flimflammer'

Resume

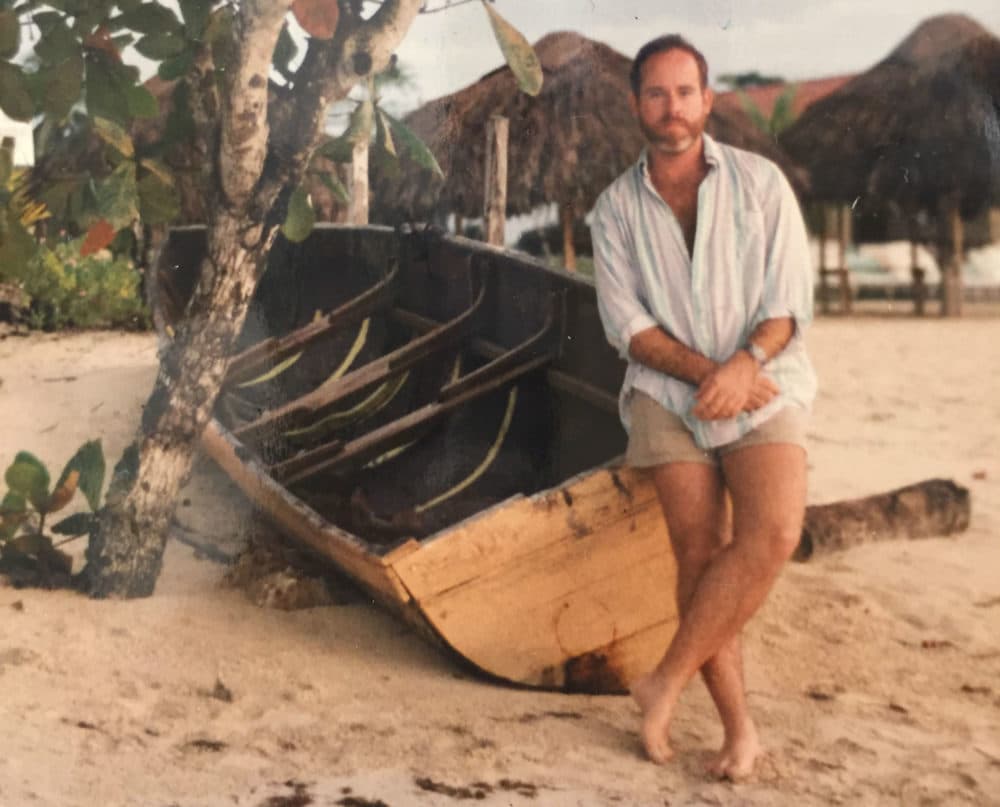

Meet Brian Michael McDevitt. He’s a clean-cut kid from a suburb north of Boston. A would-be art thief, the college dropout would go on to masquerade as a Vanderbilt in upstate New York then use his only-aspirational credentials as a writer to hob-knob in LA.

He first enters this story’s radius in 1980, by the name of Paul Stirling Vanderbilt. He started driving a Bentley around upstate New York, selling the rumors that he was a writer and had a lot of money. He took an interest in The Hyde Collection — a museum in Glens Falls, New York, inspired by the Gardner Museum itself. Built in 1912 by the heiress of a paper fortune, the museum housed its creators’ collection of Old Masters and 16th century tapestries.

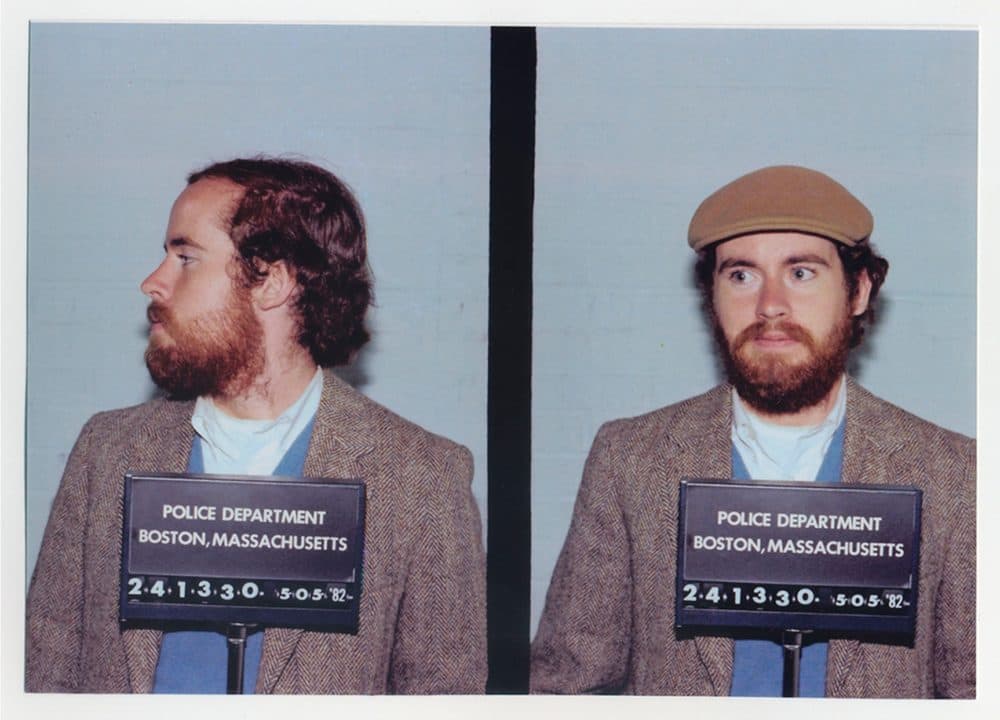

On Christmas Eve, McDevitt put a plan into action to rob the museum. He and an accomplice kidnapped a female courier driver at gunpoint. The two thieves would handcuff or tape museum employees, cut paintings from frames and empty the whole place. Then they would fence the art in southern Florida before leaving the country to retire in style. But, on their way to the museum, they got stuck in traffic — and arrested for kidnapping and attempted robbery.

A decade later, McDevitt was living in Boston when the Gardner Museum would be robbed. Given the similarities of the museums and the timing of the heists (around a holiday), it wasn’t a far-fetched idea that McDevitt would become a suspect.

McDevitt was dating a woman named Stéphanie Rabinowitz — she was in her early 20s and working in animation. Lucky for us, she kept quite a detailed diary. When they met in the summer of 1989, McDevitt told her he wrote for “The Wonder Years” and Paramount and Columbia. He also told her, right around March 15, 1990, that he was heading to the Writers Guild Awards ceremony — she would later learn they were held a different weekend that year. He seemed agitated that day, and not himself.

She didn’t hear from him again until late in the day on March 18 — the day following the Gardner heist. By then, his tone had changed and he was happy to talk to her, calmer, nicer.

By the spring of 1990, McDevitt left Boston and moved to LA — touting serious credentials as a writer for television and film. He met a man by the name of Ben Pollack. Within months of meeting, Pollack grew wary of McDevitt. Eventually he confronted him about the lies he was telling, only to have McDevitt begin threatening and harassing him.

By June of 1992, McDevitt was in deep: He faced criminal charge for harassing Pollack, he was on the verge of being ousted from the Writers Guild and exposed as a felon and a fraud. Then a New York Times article named him as a prime suspect in the Gardner heist. On live national television, he was asked if he robbed the museum – to which he responded, no, but he didn’t have an alibi. Around that time, he asked Rabinowitz to provide that for him.

She had moved out to LA at that point, and recalls the last time she saw McDevitt was on June 25, 1992 at a wrap party for a show she worked on. He claimed that he had been paid $300,000 to rob the Gardner and that he needed to leave the country.

Then, he vanished. Did he disappear because he was behind the largest art heist in history, or did he just want people to think he was?

Advertisement

Subscribe to our newsletter for the latest updates, join our Facebook group to discuss the investigation and if you have a tip, theory or thought, we want to hear it.

This episode was adapted for the web by Amy Gorel.

Senior producer and reporter Kelly Horan debunks our common notions of why people steal art:

Transcript:

KELLY HORAN: A woman of considerable means and vision and with a passion for Old Masters begins collecting them: Rembrandt, Rubens, Raphael. Her collection grows so vast, she builds an Italian Renaissance-style palace in which to showcase it. And when she dies, she leaves it all to us, her art loving heirs. But her small jewel of a museum lacks funds. Its security is weak. And in time, it attracts the scheming of thieves.

These details could only belong to one museum, the Isabella Stewart Gardner, in Boston. But what if we told you that these facts are also written into the DNA of another museum, one that is about 200 miles away, in Glens Falls, New York — the Hyde Collection.

HORAN: Did you have guards?

FRED FISHER: No guards, no. We just had volunteer ladies who, when we were open, were meandering around, and usually chit-chatting with themselves.

HORAN: Fred Fisher was director of the Hyde for a dozen years, starting in 1978, when the museum was in its 15th year. It was was the creation of the heiress of a paper fortune, who built her Italian palace overlooking the family mill in 1912. Charlotte Pruyn met and fell in love with her future husband, Louis Hyde, in Boston, at the turn of the 20th century. The pair loved art. And Fenway Court, as Isabella Stewart Gardner was still calling her museum, had left an impression. In Glens Falls, the Hydes built their more modest version — Old Masters, 16th century tapestries, center courtyard and all.

When Fred Fisher was director, the paper mill in the Hyde’s shadow still belched sulfur. There were other things that stunk, too. The endowment-starved Hyde meant that Fisher’s job as director entailed wearing many hats, or rubber gloves, depending.

FISHER: I was out sometimes working in the yard, washing windows, just a variety of things just to keep this little place clean, or cleaner than it had been. But, so it was a labor of love, it truly was.

HORAN: Imagine, then, what Fisher must have thought when he heard that a scion of one of America’s richest families — a Vanderbilt — was in town.

FISHER: I must have begun hearing stories about this guy driving a Bentley in town probably in the summer of '80. Once in a while, a guide would come in, or one of my volunteers, and say, “I just saw that Vanderbilt guy. Everybody’s talking about the Vanderbilt guy. We saw him the other day at lunch, and he’s such handsome. And I hear he’s got a lot of money.” And I, you know, being a director of a very poor museum, when you hear money, and you hear Vanderbilt, you think, “Oh wow, maybe there’s hope here.”

HORAN: Maybe. Or maybe Paul Stirling Vanderbilt, as he’d written in the museum’s visitor log, wasn’t who he said he was. His fingerprints would be among the first to be sent to FBI headquarters in the wake of the Gardner Museum robbery. Could Vanderbilt’s real identity hold the key to solving that heist?

From WBUR Boston and The Boston Globe, this is Last Seen. I’m Kelly Horan.

JACK RODOLICO: And I’m Jack Rodolico. This is Episode 8: "Flimflammer."

When Paul Stirling Vanderbilt first signed the guest book at the Hyde Collection in April 1980, he gave an address: Cady Hill House. That’s the spectacular Saratoga Springs mansion of a Vanderbilt widow, just 23 minutes down the I-87 highway from Glens Falls.

If Saratoga Springs is the belle of the ball, Glens Falls is arguably her plainer sister, who doesn’t get asked to dance.

FISHER: Cady Hill House was the Saratoga home of Marylou Whitney, who was the social butterfly of Saratoga. So I thought, “Wow!”

RODOLICO: But Vanderbilt wasn’t staying at Cady Hill in Saratoga Springs. He was staying at the Queensbury Hotel in downtown Glens Falls, where he paid his bills in cash, tipped big and aroused suspicion.

FISHER: Even though he dressed well, he spoke well, he’s a good looking guy, the so-called Mr. Vanderbilt was just maybe a little bit too — I think he might have been just giving himself away a little bit too much. But a very, very suave character.

HORAN: At the time, the Queensbury Hotel was a grand, if faded, lady. A fireside perch beneath a literary themed painting in the lobby seems to have appealed to Vanderbilt, who boasted of not only a blue blooded pedigree, but a literary one, too. He reportedly spent many hours there, writing, or telling people that’s what he was doing.

FISHER: Because he sold himself to all of us as a, as a freelance writer for The New York Times and various prestigious publications.

HORAN: You’d have to have family money to be a rich freelance writer. Vanderbilt looked and spoke and dressed like a Kennedy, people said. He sent armfuls of roses every week to a pretty local girl who would become his fiancee. He had a Bentley and a chauffeur named Giles. Even in fancy Saratoga Springs, these details might have turned heads. In humble Glens Falls, they caused a minor sensation.

On Halloween day in 1980, six months after he first came to town, Vanderbilt called on Fred Fisher at the museum.

FISHER: We sat down in the courtyard and for about an hour or so he went on and on about how he’s so interested in art, and he was writing about art, and he’s particularly interested in art theft. And that was the beginning of a little bit of concern because he went on and on about various thefts that he’d heard about, and, you know, it was clearly movie kind of stuff — catwalk, you know, walking on the ceiling, and jumping in through skylights, and he read about these things, and he was starting to write an article. It was basically, he was trying to draw out of me about what’s the security at the museum. And so I immediately — that was kind of the first red flag.

RODOLICO: And not the last. In subsequent meetings throughout the fall, Vanderbilt asked Fisher about renting the Hyde’s smaller mansion next door, as a writing retreat. Its windows happened to look directly into the museum. In mid-November, a friend of Fisher’s in the city planning office told him that Vanderbilt had been in asking to see the museum’s floor plans. Vanderbilt had implied that he was there on official business to review the Hyde’s structural details. He’d asked to take the blueprints with him, but was refused. And, Fisher says, Vanderbilt peppered him with questions about the museum’s security.

FISHER: “Are your windows secure? Do you have guards? And is there a security company that oversees your security?” And just enough — more than enough — to make me think, “Oh my gosh, what is this guy all about?”

HORAN: Fisher was torn between flickering hope that Vanderbilt really was good for a much needed windfall for the museum — and a growing feeling that something wasn’t right.

FISHER: He came once and said he was going to New York to see some of his family members. And he wanted to have a book of photographs of the paintings to show them because he was sure that if they saw these wonderful pictures they would want to give us money. Well, I could only see that as a shopping list for somebody.

HORAN: Fisher demurred. He told Vanderbilt that he and his young assistant intended to catalog the collection — but progress was slow. They had one beat up typewriter and were on a six-month waitlist for a new one, an IBM Selectric.

FISHER: . And so he said, “Well, let me see what I can do.” And one day he showed up with three of them in the back — trunk of the Bentley. They didn’t quite look brand new.

HORAN: They weren’t new. Fisher told the museum’s board he was growing concerned about this Vanderbilt fellow. And then, that very weekend, a news story about, of all things, the IBM Selectric, deepened Fisher’s susicions.

FISHER: The chair of the board called me and said, “Fred, you gotta watch '60 Minutes'! They’re talking about stolen IBM Selectrics!” And so, long story short, the following day I had someone come up here from Albany, an IBM, a rep. And he pulled — they had labels on them, “To the Hyde Collection” on each one. And when he pulled the labels off, there they were from a rental company in New York City. Um, they weren’t a gift. So that really got me pretty scared.

HORAN: Fisher began calling around trying to confirm Vanderbilt’s credentials. One of the calls he made was to an actual Vanderbilt.

FISHER: And she was very helpful, and she said, “You know, first of all, if they were a Vanderbilt they wouldn’t be driving a Bentley and being that officious — that’s just not the way we do things.” And she really laughed and said, “I’m sorry, but you oughta be calling the police. You ought to be doing something about this." So that’s when I really knew that I had a problem.

RODOLICO: Fisher did call the police. And when Paul Stirling Vanderbilt next returned to meet him at the museum, plainclothes detectives from the state’s Bureau of Criminal Investigation were there, eavesdropping. It was Nov. 26, 1980, the day before Thanksgiving.

FISHER: As we were facing each other in my office, and he said, “I've got a $30,000 check for you in my briefcase, but I’ve decided I’m not gonna give you this check because you’re just about the worst director any museum could ever have.” You know, “You should be ashamed of yourself, if the board only knew what kind of an idiot you were,” you know, on, and on, and on. And then he said, and then “I understand you’re not using the typewriters.” And I said, “Oh, well let’s talk about the typewriters.” I was a little nervous about how I was going to manage that, but after he put me down so much I was ready to...

HORAN: To call his bluff?

FISHER: [Laughing.] Yeah. And then he was very kind of fishy after that. And, you know, he kept going on about, “Well, I’ll take ‘em back if that’s the way you feel.”

HORAN: Well, what did you say to him about the typewriters?

FISHER: I just said, “Lookit, fella, we’ve just — we had it evaluated, and they’re not — they’re rentals! They’re not, you know — where’d you get these?” And he was very red faced. He realized that he was kind of caught short.

RODOLICO: Fisher says Vanderbilt was furious. He loaded his typewriters into his Bentley and left. So did the detectives. They’d agreed that Vanderbilt was a condescending jerk but said they couldn’t arrest him for it. Fisher decided to keep the glass mug he’d served Vanderbilt coffee in — just in case having fingerprints would come in handy.

FISHER: I carefully washed it out a little bit of it and then put it in a plastic bag and put it away. I’m sorry I didn’t save that cup for a momento.

HORAN: Very Columbo of you.

FISHER: [Laughs] Right. Obviously I’d seen way too many movies.

RODOLICO: What came next was straight out of one.

HORAN: At 5:30 in the morning on Christmas Eve, 1980, Fred Fisher, then the 40-year-old director of the Hyde Collection in Glens Falls, New York, awoke to a telephone call from police. Someone had tried to rob the museum.

Advertisement

FISHER: Vanderbilt immediately came to mind. There was no doubt in my mind that’s who it was.

HORAN: That is who it was. Only, Paul Stirling Vanderbilt was really a 20-year-old college dropout named Brian Michael McDevitt, from an upper middle class coastal town about 12 miles north of Boston.

RONALD KERMANI: Brian McDevitt could never walk into Saratoga Springs or Glens Falls, or any spot in America today and claim that he was a member of a Fortune 500 family. He would last about 13 seconds, or two beers, whichever came first.

HORAN: But in a pre-Google era, Brian McDevitt could. And when he did, this man, Ronald Kermani, was an award-winning investigative reporter for the Times Union newspaper in Albany, New York.

KERMANI: Here’s a clean-cut kid out of the middle-crust of Boston, coming to an area he has no idea where he is or what he’s doing here. He just lands here to be near the horses and the beautiful people and the money that he’s going to take every opportunity to make himself a fixture and a player in town. He’s got the cash and the chutzpah to do it.

HORAN: McDevitt had financed his charade with about $100,000 he’d stolen from some safe deposit boxes in Boston in the fall of 1979, where he’d been volunteering for Sen. Ted Kennedy’s presidential campaign. A Boston detective had been looking for him since. As far as he knew, McDevitt had just up and vanished.

When he was arrested in Glens Falls, McDevitt explained his alias to police by saying “I was doing this to avoid trouble with Massachusetts authorities regarding a particular legal affair.” That’s con man code for felony. And now he was facing multiple felony charges in Glens Falls, too.

RODOLICO: Ronald Kermani was in the newsroom on Christmas Eve, when the call came in about two men arrested on kidnapping and robbery charges.

KERMANI: And police are telling me that these two guys, one 20-some years old, and one 30-some years old, kidnapped a woman, a female courier driver at gunpoint, and had elaborate plans to rob this museum of between 30 and 50 million dollars of classical artwork. And I said, “Wow. Are you kidding me? This is not April Fools, it’s Christmas Eve.” He said, “No, Ron,” the cops said, “No Ron. This is true, they’re sitting here in a holding cell as I tell you.”

RODOLICO: Kermani’s Christmas morning story about Brian McDevitt and his planned heist on the Hyde Collection was in the next day’s paper.

FISHER: There was this unbelievable article that just kinda blew my mind, you know, just sitting there reading it to my wife thinking, "I could be dead." [Laughing.] Oh my, God. I had no idea this was so serious."

HORAN: This was big news for a city of 15,000 best known for an annual hot air balloon festival and a minor league hockey franchise. McDevitt’s confession to police reads like a screenplay for a Hollywood caper. His tone is almost boasting. He told police, “I drew up equipment lists such as vehicles that would be needed. I reviewed the problem areas, such as whether there was a panic alarm someone could push.”

McDevitt had bought ether, handcuffs and tape for subduing museum employees. He’d bought tool kits at Sears. He told police, “They were for various problems we would run into while removing the paintings from the walls of the Hyde Collection.” McDevitt’s accomplice told police they were prepared to cut some paintings from their frames. They’d planned to empty the place.

KERMANI: Their goal was to fence the stuff in southern Florida. It may have been worth $50 million. They were boasting that their take might be $15 million. They were going to retire in style and just jump the gun and get out of the country fast. Of course, what happened was, believe it or not this is like the Keystone Cops, they got stuck in traffic in beautiful downtown Glens Falls, the clock kept ticking on them, and the Hyde Museum closed, and the alarm was set, and they’re sitting in a truck with an unconscious FedEx driver, a couple of empty cardboard boxes, duct tape, a pellet pistol and an invitation to the county jail.

HORAN: About that FedEx driver. She was 26-years-old and had been on the job for five years when McDevitt’s accomplice handcuffed her, covered her eyes and mouth with tape and knocked her out with ether in the back of her truck. Fred Fisher says McDevitt appears to have targeted her specifically.

FISHER: He was contacting, ah, FedEx and mailing sham packages quite often only to find out who’s on the routes, who the drivers were, and really spent a lot of time, a lot of effort trying to figure out how best to do this.

HORAN: Almost 40 years later, the FedEx driver didn’t want to talk to us. She wouldn’t even come to the phone. Her husband said she had no desire to relive what had been a terrifying experience. In her statement to police, the FedEx driver says this about McDevitt: “He said he wouldn’t harm anyone and that he isn’t that kind of a person. He said, couldn’t I tell that by the way he was treating me? He said that if I helped him, he would make it worth my while. He said he would give me $25,000 for it. I said I didn’t want the money. He said that he could put it in a Swiss account so it would be there whenever I wanted it. He said that he was going to rob from the rich to give to the poor.” She reported that McDevitt had also told her that he risked ruining his family name, by which, of course, he meant Vanderbilt.

FISHER: When she gave a statement to the police she said that she recognized this voice. She was blindfolded, but she had heard McDevitt’s voice in the Federal Express truck. And she could recognize this voice, and she was pretty sure it was him.

RODOLICO: The FedEx driver noticed something else. She told police, “The dark mustache didn’t go with the blond hair.” McDevitt and his accomplice had worn fake black mustaches. And early reports out of Glens Falls put the two would-be thieves in FedEx uniforms.

HORAN: So did they or didn't they dress up as Federal Express drivers?

FISHER: They did not. McDevitt tried to buy uniforms. Wherever he did this he was treated rather strangely. And I think he backed away thinking maybe that would — maybe somebody would get the idea of what they were doing, but they did attempt to do it.

RODOLICO: McDevitt’s accomplice was a divorced father who was working as an assistant manager at the Queensbury Hotel. He told police that he’d gone along with McDevitt’s scheme out of fear. “He mentioned love for my son, and it would be a shame if anything happened to him.”

HORAN: To read the accomplice’s police statement is to realize that he had bought McDevitt’s cinematic worldview wholesale. He recounted that, pre-heist, McDevitt had given them and the operation code names. They’d boned up on art theft by reading the book “Thinking Like A Thief.” And post-heist, their plans included taking a Concorde supersonic jet to London, or maybe Zurich, and hiding their millions with the help of a financial planner in Los Angeles.

KERMANI: The headline is: The art heist that failed, but not for lack of imagination.

HORAN: Ronald Kermani could not get enough of this story. He drove to McDevitt’s hometown, found a payphone and started cold calling anyone who might have known McDevitt. He went to the library and found McDevitt’s high school yearbook. The insights he gleaned filled a three-part profile published in the Times Union newspaper. The first installment came out on Jan. 4, 1981.

KERMANI: Even in high school, Brian Michael McDevitt was the consummate hustler. At his best, classmates recall, he was articulate and aggressive. At his worst, he was brash to the point of being obnoxious. And today he’s in the Saratoga County jail in lieu of $50,000 bail, accused of plotting an elaborate robbery designed to net him millions in art treasures.

HORAN: Brian McDevitt served two years for kidnapping and attempted robbery. He was living in Boston in 1990 when the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum was robbed a decade after his Glens Falls misadventure. Fred Fisher says, when he heard the news of the Gardner heist, he knew right away who did it: Brian McDevitt.

FISHER: Immediately. Absolutely immediately. You know, not only I, myself, but my former staff, you know, we talked. The first thing that came out of his mouth was, "For God's sake, Fred, did you — it's got to be McDevitt. It's got to be McDevitt.

HORAN: Why do you think that is?

FISHER: It just — it was so clearly a similar incident, you know, timed around a holiday, disguised as somebody else, duct tape, and, you know — I guess they did have handcuffs, I think, at the Gardner. The similarities were just very much there.

HORAN: In the summer of 1989, Vermeer’s The Concert still hung in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. So did Rembrandt’s only seascape, Storm on the Sea of Galilee, along with eleven other works of art that would vanish before dawn on March 18, 1990.

And on July 6 that summer, Brian McDevitt met a young woman who would factor in his life for several years to come. Her name is Stéphanie Rabinowitz.

HORAN: Did he tell you where he was from?

STEPHANIE RABINOWITZ: New York, somewhere in New York. He was pretty quiet about his past.

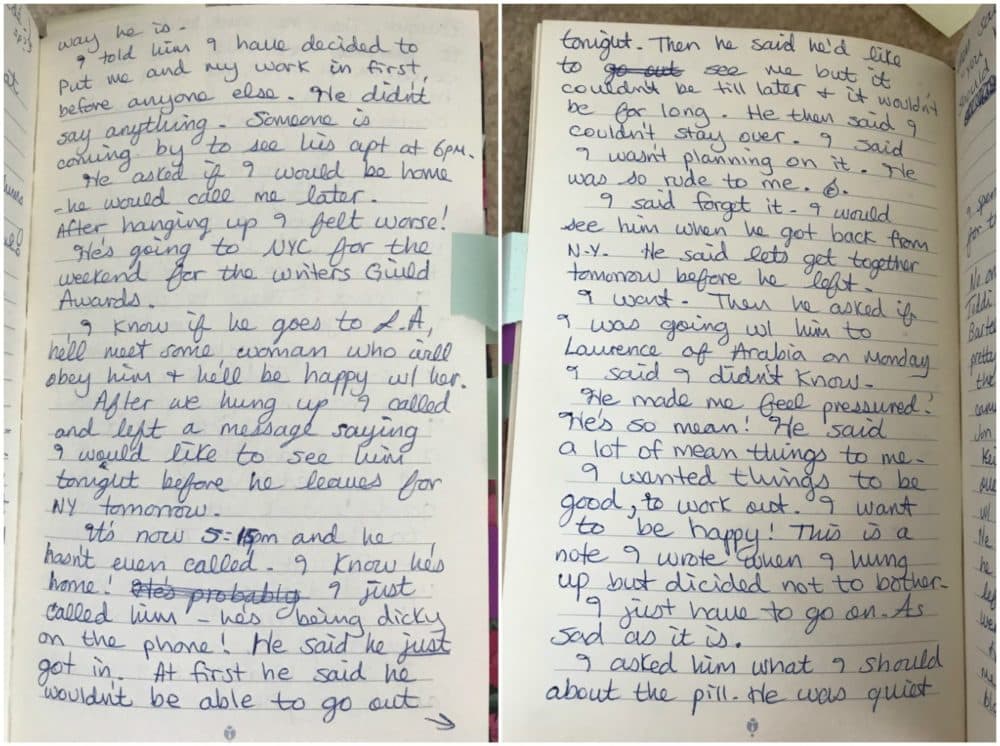

HORAN: She’s a photographer now, but then, Rabinowitz was 22, living in the Allston neighborhood of Boston, and working in animation for film and commercials. McDevitt was just a few weeks shy of his 29th birthday when they were introduced to each other at a comedy club. Rabinowitz went home and wrote in her diary:

RABINOWITZ: He has beautiful eyes, a mix between blue and green. He’s a screenwriter for "The Wonder Years" and Paramount and Columbia.

HORAN: His name and eye color might have been true, but nothing else was. Brian McDevitt had dropped the Vanderbilt ruse but was still laying claim to a literary status he didn’t have. But Rabinowitz didn’t know that.

So when, six months into their relationship, McDevitt told her that he was headed to New York City for the Writers Guild Awards ceremony, she believed him. It was three days before the Gardner Museum would be robbed. Thursday, March 15, 1990. Rabinowitz, who kept a detailed diary at the time and shared it with us, recalled that McDevitt wasn’t himself when they’d spoken that day by phone.

RABINOWITZ: He seemed agitated and nervous, and just not welcoming, or lovey dovey or inviting.

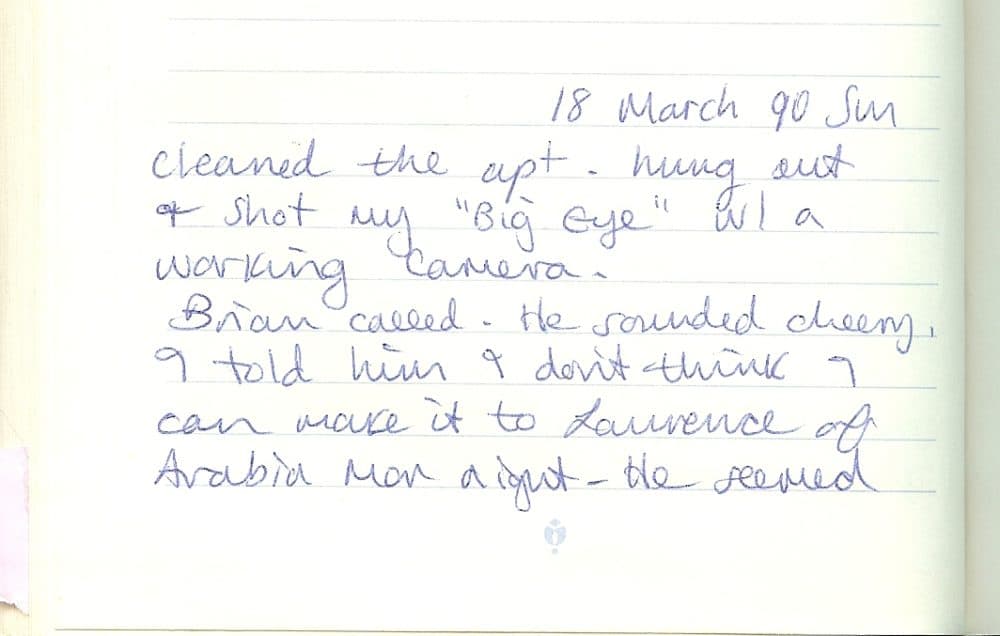

HORAN: She didn’t hear from McDevitt all weekend. But his tone had altogether changed by the time he called her late in the day on Sunday, March 18.

RABINOWITZ: Oh, he was happy, cheery, happy to be back. Happy to talk to me, you know, looking forward to getting together again, much calmer than before he left, much nicer and more at ease with himself — just his whole demeanor was much nicer.

RODOLICO: Former FBI Special Agent Thomas McShane was also in Boston on March 18, 1990. He’d been among the first on the scene of the robbery at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.

THOMAS MCSHANE: It was of course taped off with the yellow evidence tape that we use. The frames were all on the floor, scattered in a real haphazardous way. And it looked very disturbing. And we were just praying that they didn't ruin these paintings by the way that — what they left behind, it looked like a disaster.

RODOLICO: McShane was an undercover art recovery expert for the FBI for a quarter of a century. By his lights, he returned some $500 million worth of stolen and forged art. There was an El Greco, a Rubens, and a Rembrandt that had been on loan from the Louvre when it was stolen.

HORAN: And so where in your — in the spectrum of all these cases, where is the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum for you?

MCSHANE: That is top priority on my list.

RODOLICO: McShane says there was one suspect who was among the first to have his fingerprints sent to FBI headquarters. It’s the same suspect that McShane says he would still put his money on for having pulled off the Gardner heist.

MCSHANE: Brian Michael McDevitt. He was interviewed by the FBI and immediately afterwards he took off to California. This is a con man of a nature of Bernie Madoff.

HORAN: So, you put Brian McDevitt in that class of con man, like the best you've ever seen.

MCSHANE: Exactly.

HORAN: In the spring of 1990, Brian McDevitt left Boston and moved to a hilltop bungalow above Mulholland Drive in Los Angeles. He joined the West Coast branch of the Writers Guild, formed a production company, and touted serious credentials as a writer for television and film.

BEN POLLACK: First he's this sort of like, you know, aristocrat who's a famous writer, then he's none of those things, and then not only is he none of those things, he's a crook, and not only is he a crook, he's a monster.

HORAN: Ben Pollack directs television commercials and music videos now. In mid-July of 1991, when he met Brian McDevitt at the Writers Guild, he was 19, just getting started in the business, and naïve.

POLLACK: He was introduced to me as this great writer who had this deal with Paramount doing all these wonderful things. And he said "Who are you? I like your attitude. Give me something — you know, send me something that you wrote. I'd love to read it." So I'm like, "Oh! This is exactly why I came there."

HORAN: Pollack was completely taken in by McDevitt.

POLLACK: Sophisticated, and entertaining, and charming and giving, articulate, intelligent, fun person, kind of like an older brother. And he had big stories that you just believed. You know, that kind of guy.

RODOLICO: But within six months of meeting Brian McDevitt, Pollack would tell police, he’d grown so leery, he hired a private detective to dig into McDevitt’s story. He learned that McDevitt’s business partner was himself wanted by the FBI. That man would be extradited to Chicago on 12 counts, including grand larceny. Pollack learned that nothing McDevitt had told him was true. Not the big things, like his writing credits, and not even the small things, like his claim that he owned his home in the Hollywood Hills. Pollack made more calls, starting with the producers of a major Hollywood film that McDevitt had claimed to have been working on.

POLLACK: I asked them, I said, "you know, I understand Brian McDevitt was a writer on this movie." And they were like, "Brian, who?" And you know, then I started to tell them what was going on, and they got fascinated by that story, and they checked out other things. So they were able to check out other parts of his resume. And then they gave me the telephone numbers to call other people. And then I did that, and I checked this one, and that one. I called the New Yorker, and I called the Guardian in London, you know, where he said he had published these stories. And s---, sure enough, nobody knew who he was. It was that simple! All you had to do was call. All you had to do is check it out. But it was so brazen, nobody did. I realized that I'm now with a total flimflam artist, and I have to get out of it, you know.

RODOLICO: Pollack confronted McDevitt.

POLLACK: I say, "I found out all these things about you. I just want to get out of this company. That’s all I want. I was — my heart was pounding. My mouth was dry. I was thinking more for him, how embarrassed I would be if somebody found out that I was a flimflammer and caught me red-handed. You know, that's really what I was thinking. Anyway, that's when it all started. He was cool as a cucumber. He told me how it was going to go, and he threatened me. He said, "If you tell anybody what you discovered, you know, I'm going to... I'm going to do you in." And then he was sort of, straight up to my face. I mean, he was doing the stuff that you just think, oh no, that's stuff you'd read — or see in a movie, you know, from some wacko. That really never happens. But no, he's that guy who did all the things you didn't think anybody would do.

HORAN: McDevitt began quietly tormenting Pollack, waging a kind of creepy psychological warfare. He’d knock on his door in the middle of the night, and then whistle from somewhere in the darkness when Pollack opened up. And he began calling Pollack over and over. Sometimes a hundred or more times a day — just to hang up when he answered.

POLLACK: The hang up stuff was the real, real insight to this guy. He was sitting somewhere in the dark, or whatever, and calling me over and over and over and over, day after day after day after week after week after week. What was going through his mind when he was doing that? It was incessant.

HORAN: It took more than six weeks, but by April of 1992, Pollack was able to convince the police that he knew who was behind the calls. A trap on Pollack’s phone proved him right.

POLLACK: All I knew was that Brian was so afraid of going to jail even for 10 seconds — and this is what he told me: that he would do anything not to go to jail. And he felt like he was going to go to jail because he got caught doing this thing with the phone.

HORAN: June of 1992 brought a perfect storm of trouble for Brian McDevitt. He faced criminal charges for harassing Ben Pollack. He was on the verge of being ousted from the Writers Guild, exposed as a felon and a fraud. And then, an article in The New York Times outed him as a prime suspect in the Gardner heist. There followed a similar article in The Los Angeles Times, and then another, in The Boston Globe. And on the heels of that, 60 Minutes came calling. Morley Safer, the show’s late correspondent, asked McDevitt on national television if he robbed the Gardner Museum. No, McDevitt said. But, he admitted, he didn’t have an alibi. There followed a summons to a grand jury back in Boston. The walls were closing in. It was around that time that McDevitt asked Stéphanie Rabinowitz, who had by then also moved to LA, to be his alibi with the FBI if they asked her about him and the Gardner heist.

RABINOWITZ: Yeah, I shut it down because the minute he said, "I really need you to lie to the FBI for me," right there I was like, "I cannot lie to the FBI." And then asking me to be his alibi — you know, I didn't put two and two together because I wasn't thinking then like, "Oh, he was at the Writers Guild."

HORAN: Brian McDevitt might have been in New York City the weekend the Gardner Museum was robbed, but he wasn’t at the Writers Guild Awards, as he told Rabinowitz. They were held that year in April. Rabinowitz last saw McDevitt on June 25, 1992, at a party for a show she worked on. She wrote about it in her diary and recalls that meeting.

RABINOWITZ: And he told me that this guy had paid him — I believe and remember him saying $300,000 to cut out the art pieces in the museum to give it to him, and then all he would have to do is collect the money, and get out of the country. And then he could live the rest of his life being taken care of. And he offered me to come with him. He actually asked me so much. He's like, "Please, please come with me. We could live a great life together. I'll take care of you for the rest of your life." And as great as that sounded for a 20-year-old who's kind of struggling, I couldn't do it. Yeah, I was a little tempted and I thought about it, but I thought, "No, I can't do it. And I'm not going to live off of a whole lie," and just of everything that had happened. So I told him I couldn't do it. He was pissed again, mad, upset, hurt. That was the last time I saw him.

HORAN: She never heard from him again. But Rabinowitz did hear from an FBI agent about a month later. Rabinowitz says the agent had come to her apartment to question her about McDevitt and the Gardner heist. The agent couldn’t question McDevitt himself, though, because he’d vanished. Again.

RODOLICO: Nat Segaloff is a writer in North Hollywood who’s written a screenplay about Brian McDevitt. He knew him both in Boston and in Los Angeles. And he liked him.

NAT SEGALOFF: I'm a reporter. I started off as a reporter. I was cynical. And I've dealt with so many scumbags in the film business, both in exhibition and distribution, that an art thief, to me, is a step up.

RODOLICO: Two years after McDevitt left LA, he called Segaloff.

SEGALOFF: Absolutely out of the blue, in October of 1994 I got a phone call from him. He said he was in Rio de Janeiro waiting for the statute of limitations to run out. At that point I kind of got the idea that somebody was after him. He said he was in Brazil because there was no extradition treaty with the United States. And he also said that he had got wind from the grand jury that there might be an indictment handed down, so he fled the country.

RODOLICO: Segaloff didn’t hear from McDevitt again for another eight years, when he received an email in December of 2002.

SEGALOFF: We just started writing back and forth. We have a voluminous correspondence. Mostly he would send me articles about art heists all over the world and we would talk about movies and we'd talk about politics, especially the difference in politics between America and Central America, because at that point he was living in Medellín, Colombia.

RODOLICO: That’s where McDevitt was reportedly last seen. He’d set up a phony English translation business.

HORAN: Did you ever ask him outright if he had pulled off the Gardner heist?

SEGALOFF: I didn't ask Brian directly, but I tried to be coy about it because by this point I was quite curious. He sent me a how to guide in a sense of how to rob a museum. He told me about other people who were involved. He told me about how the FBI was after him. These didn't come off as paranoid. These came off as sensible reports. Putting all the pieces together I really did believe that he did it, but he wasn't going to tell me directly unless I'd broken the code somehow and got him to tell me.

RODOLICO: Segaloff heard from McDevitt one last time: May 10, 2004. He said he was calling from Medellín, Colombia, and Segaloff recorded the call.

MCDEVITT: It’s Brian McDevitt.

SEGALOFF: Certainly is. How are you?

MCDEVITT: Well that’s why I’m calling, Nat.

SEGALOFF: What?

MCDEVITT: I didn’t want to do this over the internet because, ah, I just wanted to talk to you for a coupla minutes and I don’t have a lot of time. Ah, How are you? [fade out]

SEGALOFF: I’m fine. I’m holding my own here. You know how it is.

RODOLICO: McDevitt got down to business. He’d been ill. It was serious. He wanted Segaloff to know.

MCDEVITT: Look Nat I have to go back to the hospital tomorrow. You know, I didn’t want you to hear about it late or anything else. You know I consider you one of the few friends that I have left. So, everybody else has pretty much abandoned me, including my family, and I just felt that you should know and, I hate to kinda call you like this, but I realize that I haven’t really been as prolific as I used to be on the internet, really since I got back from the hospital in January. So let me just tell you what’s going on. Doesn’t look like I’m going to be living to your ripe old age, that’s for sure...

SEGALOFF: What?

MCDEVITT: When I got out of the hospital they asked me to come back and they told me I was HIV positive. Needless to say that came as quite a shock. The fact is, Nat, that I’ve slept with dozens of women down here and...

RODOLICO: McDevitt told Segaloff he had pneumonia and that he’d been having difficulty breathing.

MCDEVITT: But anyway, the point, Nat, is that I am just running out of time. I don’t want anyone to know but I wanted you to know. because you’re one of the few people that has been so nice to me over the last year or so, I, I wanted to let you know what was going on, because I really don’t have anybody to tell.

RODOLICO: McDevitt sounds like a man facing his own death. In June, Segaloff heard from McDevitt’s sister that her brother had died 17 days after that phone call. May 27, 2004. Brian McDevitt was 43 years old.

HORAN: Several of the people who knew Brian McDevitt — his former girlfriend, the museum director he tried to scam, the aspiring screenwriter he flimflammed — don’t believe he’s dead. Neither does former FBI agent Thomas McShane.

MCSHANE: We could dig him up and make sure that there is a body beneath the ground because I don't believe there is.

HORAN: What does Nat Segaloff, perhaps McDevitt’s one true friend, think?

SEGALOFF: I don't believe Brian faked his death for a very, very simple reason: He couldn't keep a secret with me. If he called me before going into the hospital and said he didn't expect to come out, maybe that was being overly dramatic, but he's the one who got in touch with me on every single occasion once he left Boston. I don't believe he could keep it quiet.

HORAN: The Gardner Museum’s director of security, Anthony Amore, doesn’t think so, either. He says he’s seen McDevitt’s hospital bills and Colombian death certificate. He says the guy is dead. What’s more, Amore says the only museum Brian McDevitt was capable of robbing was the one in his own mind. He wanted to rob the Hyde Collection, after all, but failed. On a drive through McDevitt’s hometown, Amore dismissed the Brian McDevitt theory entirely.

ANTHONY AMORE: The other thing about him being involved, though, is you have to think, this guy, his whole life was about self-aggrandizing. He wanted the attention. Right, after the statute of limitations had run out he had every opportunity to have come forward. And said he had them and would have been, you know, "I'm the world's greatest art thief. I pulled off the biggest heist in history and I'm not even arrested for it."

HORAN: Maybe so. He is in a good position to know. But then, so is this guy...

RANDY: He was the one that cuffed me. I feel, you know, 90 to 95 percent certain that it was him.

HORAN: Remember the security guard we spoke to in the first episode, the one we are only calling by his first name, Randy? He says that when he saw photos of all of the Gardner heist suspects, there was only one that jumped out at him. It was the thief who had treated him in an otherwise courteous manner — he’d readjusted his handcuffs, told him he’d make it worth his while if he cooperated, apologized for having to do this.

RANDY: Yeah I mean, I feel like 90 to 95 percent sure that that's — that he was the guy.

RODOLICO: Next time: We go from the prospect of digging up the dead, to digging up the Gardner treasure.

Last Seen is a production from WBUR and The Boston Globe. Digital content was produced in partnership with The ARTery, WBUR's arts and culture team. Read more on the Gardner heist from The ARTery.