Advertisement

Commentary

The desegregation of Boston’s schools was a long time coming

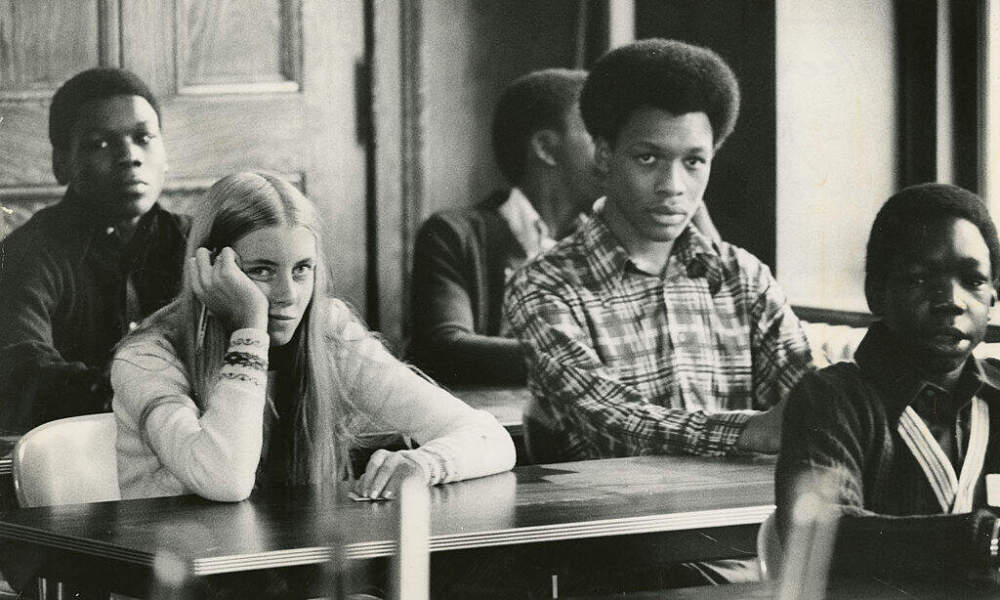

In the 50 years since the court decision that finally desegregated Boston’s public schools, praise for U.S. District Judge Arthur Garrity’s ruling in Morgan v. Hennigan has been scant. Shortly after Garrity released his decision on June 21, 1974, many white Bostonians vowed that they would never go along with a plan that bused children to different neighborhoods. Their violent resistance captured national and international headlines as chaos gripped the city.

Nobody came to Garrity’s defense. An anti-busing movement rose in Boston and throughout the nation. President Gerald Ford publicly professed his disagreement with Garrity’s decision. A freshman senator from Delaware, Joe Biden, derided the “federal bureaucrats” who had drawn up busing orders and thus jettisoned “good old common sense.”

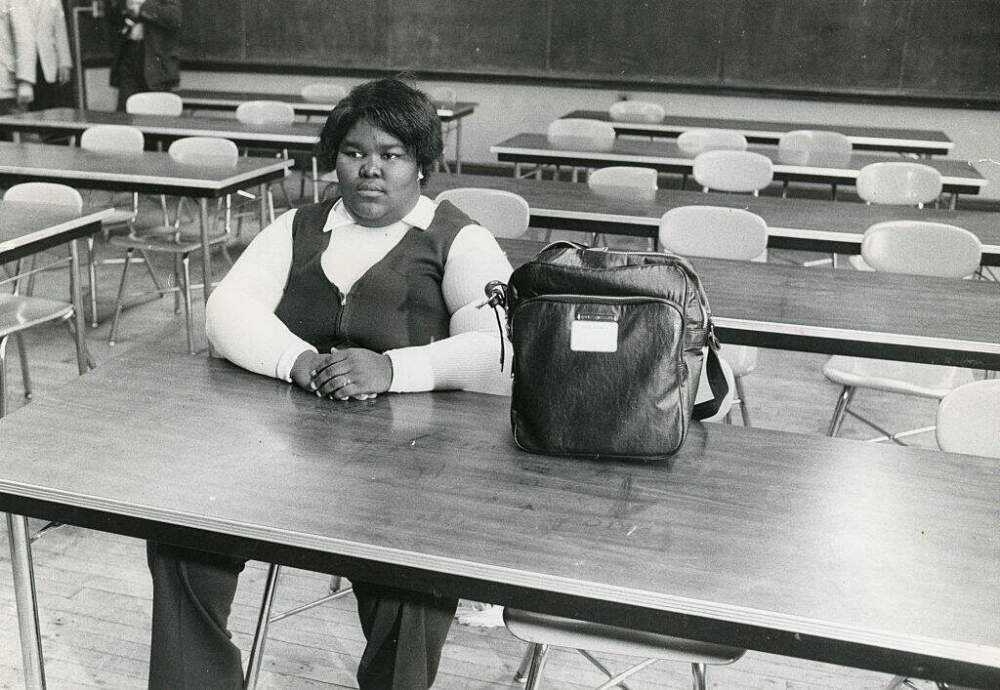

Through the decades, a misconception has prevailed: Most observers have viewed Garrity’s order as one that was foisted upon the city from on high, as though no Bostonians wanted the desegregation that he initiated. This view erases the years of struggle waged by Black parents and activists. When the Boston NAACP filed its lawsuit in 1972, it did so on behalf of 15 Black parents and 43 children. Certainly, no Black parents had been clamoring to send their children to South Boston High School. Yet they desperately wanted to get their children out of their segregated and failing neighborhood schools.

By the time of Garrity’s decision, Boston’s elected officials had rejected every other proposal that might have desegregated the schools. And they had convinced many of their constituents that desegregation would never happen. Their vehement resistance helped ensure that when desegregation finally did arrive in September 1974, many white Bostonians would greet it with fury.

This was 20 years after the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education, and nine years after the state of Massachusetts passed the Racial Imbalance Act. Even with that state law on the books, the Boston School Committee (the school board for Boston’s public schools) continued to pursue a host of policies that increased the number of segregated schools.

It is important to distinguish between Garrity’s findings and his remedy. His findings, that the Boston School Committee had “knowingly carried out a systematic program of segregation,” were incontrovertible. They were based on the most thorough study of the School Committee’s actions and records. It was his remedy — the use of school buses to achieve desegregation, and specifically, his pairing of Roxbury with South Boston — that proved controversial and explosive.

Garrity’s decision must be viewed in light of the grassroots movement for desegregation that predated it.

In the months and years leading up to Garrity’s decision, it was dogged Black parents and activists who placed the issue of segregated schools before judges and policymakers, and who continued applying pressure until those officials responded.

Ruth Batson played a central role in that struggle. Batson, who had three daughters in Boston Public Schools, realized that as long as the city’s schools remained racially separate, they would never be equal. “Where there were a large number of white students, that’s where the care went,” she said later in an interview. “That’s where the books went. That’s where the money went.” Batson dove into politics and activism, running (unsuccessfully) for a seat on the Boston School Committee in 1959. In the early 1960s, she became head of the Boston NAACP’s Education Committee. On the night of June 11, 1963, Batson delivered an impassioned speech before the Boston School Committee and its infamous chairwoman, Louise Day Hicks. With 125 supporters gathered behind her, Batson spoke that evening “because the clamor from the community is too anxious to be ignored.” She explained that Black children in Boston attended schools that were racially segregated, underfunded and overcrowded, and that provided no semblance of educational opportunity. She asked committee members simply to acknowledge the existence of segregation in Boston’s schools. And she was rebuffed.

Advertisement

Students, parents and community leaders turned to collective protest. One week later, they participated in a student “stay out for freedom,” when 3,000 students boycotted the schools and attended classes at “freedom schools” instead.

They organized a larger "stay out" in February 1964, as did hundreds of thousands of Black students across the country. The Boston movement soon attracted the interest of Martin Luther King, Jr. In April 1965, King led a march from Roxbury to Boston Common. More than 20,000 people marched with him, urging the state legislature to pass the Racial Imbalance Act. To maintain a focus on the issue of school segregation, Rev. Vernon Carter waged a 114-day vigil in front of the offices of the Boston School Committee.

The School Committee had segregated the schools and then poisoned the atmosphere. It sacrificed Boston’s Black students and left Garrity with no good choices.

Black parents “tried everything,” Batson recalled. “They tried the appeals. They tried going to the school committee.” Tom Atkins, president of Boston’s NAACP branch, repeatedly met with the Boston School Committee and the superintendent, but never gained an inch. “Black parents in Boston were committed to doing whatever had to be done to rescue those children from schools we knew were killing them educationally,” Atkins recalled. Out of desperation, the NAACP turned to the federal court. It was “a last resort,” Atkins said.

Garrity ultimately ordered that a desegregation plan had to begin when school restarted in the fall. But when Ruth Batson discovered that some of Roxbury’s children would have to attend South Boston High School, she worried: “We were sunk.”

She knew the racism that enveloped South Boston, and she understood that South Boston High School was no educational Promised Land. Still, many Black parents saw Garrity’s order as an important first step. By that point in 1974, the only other option was continued segregation.

Tom Atkins compiled devastating evidence in support of the busing plan. Under his direction, the Boston branch of the NAACP had conducted a survey among Black students who were bused to South Boston High School. Reading the survey results was, Atkins later said, “like being hit with a sledgehammer,” he recalled in a 1988 interview. “What I saw was that these kids couldn’t spell. They could not write a single, declaratory sentence. They couldn't spell the name of their street. They couldn't spell the name of their community. They couldn't spell Roxbury. They couldn't spell Boston as in South Boston. They couldn't spell high as in high school. They couldn't spell Negro. They couldn't spell Black.” Atkins cried, but he also felt emboldened. “We had to get those kids out of those schools and this proved it.”

Garrity’s busing plan was not perfect. Far from it. But he did recognize a constitutional violation and he attempted to offer redress. That was much more than could be said about the Boston School Committee or the city’s anti-busing army.

The School Committee had segregated the schools and then poisoned the atmosphere. It sacrificed Boston’s Black students and left Garrity with no good choices.

Perhaps Ed Brooke summed it up best. Brooke was serving in his second term in the U.S. Senate when buses started to roll through Boston in the fall of 1974. He was the only African American in the Senate -— the first since Reconstruction. To his constituents who had complained about his strong stance on school desegregation, Brooke responded in 1974 with a letter that emphasized the following: “There is a less than perfect busing plan, by order of a federal judge, only because” Boston’s local leaders “chose to lull you to sleep about what the law meant and mandated.” They left the hard work to Garrity.

Half a century later, Garrity looks less like a judge who discarded “good old common sense” and more like one who tried as best he could to confront and address the difficult problem before him.