Advertisement

A 1986 summer camp murder devastated two families. Here's their story

Resume

Why did Jacob Wideman murder Eric Kane?

In 1986, the two 16-year-olds were rooming together on a summer camp trip to the Grand Canyon when Jacob fatally — and inexplicably — stabbed Eric.

That night, Jacob went on the run, absconding with the camp’s rented Oldsmobile and thousands of dollars in traveler’s checks. Before long, he turned himself in and eventually confessed to the killing — although he couldn’t explain what drove him to do it.

It would take years of therapy and medical treatment behind bars before Jacob could begin to understand what was going through his mind that night. It would take even longer to try to explain it to his family, to his victim’s family and to parole board members, who would decide whether he deserved to be free ever again.

This debut episode of Violation, a podcast from The Marshall Project and WBUR, introduces the story of the crime that has bound two families together for decades.

Jacob’s father, John Edgar Wideman, is an acclaimed author of many books on race, violence and criminal justice. He spoke with Violation host Beth Schwartzapfel in a rare, in-depth interview about his son’s case that listeners will hear throughout the series, including this premiere.

Listen to new episodes each Wednesday, through the player at the top of the page, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Violation will also be available on The Marshall Project's site and on Here & Now from NPR and WBUR.

Show Notes:

- The Marshall Project: Life Without Parole

- More about John Edgar Wideman

Read the transcript:

Two sons, lost

Beth Schwartzapfel: Would you be willing to read a couple of passages? I brought some of your books with me that speak to some of these issues.

John Wideman: Depends. I don’t want to get into anything that even begins to feel like “he said, she said,” cause that ain’t going no where.

Beth Schwartzapfel: I flagged a couple of passages. This passage here that I’ve marked with the red pen.

John Wideman: I don't know if I could read this — particularly after looking at that picture of him.

Beth Schwartzapfel: This is John Edgar Wideman, author of more than a dozen books. English professor, Rhodes scholar, MacArthur “genius.”

I’ve been reading John Wideman’s books for years, intrigued first by his lyrical explorations of the criminal justice system, of racism and class and privilege. And then, later, even more intrigued when I learned how these themes played out eerily, tragically, in the life story of his middle child, Jacob.

When I finally arrived at his Manhattan apartment on one of the first blustery cold days this winter, it felt like I was walking into something intensely personal — something that as a journalist I’d been fascinated by for at least a decade, but as a human, I was mindful was a painful, private story.

As a rule, John doesn’t talk publicly about Jake, at least not directly — even when he’s asked about it by Terry Gross on Fresh Air, as he was in 1994.

Terry Gross on Fresh Air: Do you think you'll ever write a more extensive piece about your son, Jake, or is that something that you think you might never care to share in detail with the public?

John Wideman: Well, the advantage of being a writer is you talk about things in your own way.

Terry Gross: Right.

John Wideman: Sometimes people can look at your biography and make guesses about what, in fact, you're writing about and thinking about. But other times they can't. It's a complicated way of taking the Fifth, if you will.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Years after he sidestepped Terry's questions, John is finally letting someone in to ask him about his middle child. And he has a specific reason: He'd like to see Jake get out of prison.

This is not my reason for talking with John. It's my job to tell you everything I can find out about what really happened, and why. Everyone talking to me for this story has their own reasons. Everyone has their own version of the truth, too. John Wideman can relate to that.

John Wideman: I'm a fiction writer. And a novelist. I also write nonfiction. In my view, it's very hard to distinguish, often, among those genre. And sometimes it's impossible. And maybe they're all the same.

Beth Schwartzapfel: As a longtime fan of John Wideman’s writing, I can tell you that much of it is animated by this idea that good stories contain some essential truth, regardless of whether they’re actually true. Or, that in some situations, true accounts may in fact be less true than fiction.

One of the people who I’m hoping will help me understand what’s real and what’s false is John’s son, Jake Wideman.

Prison phone message system: This call will be recorded and subject to monitoring at any time.

Beth Schwartzapfel: I talk to people in prison all the time. I’m used to the noise, the terrible sound quality, the robot lady constantly interrupting to warn you that you’re talking to a prisoner and it’s costing a small fortune and your calls are being recorded and you’d better hurry up.

Prison phone message system: …one minute remaining….

Jake Wideman: I think, Oh, okay, we're going to get cut off.

Beth Schwartzapfel: But ever since we started talking, in phone conversations I could record, and at in-person visits the state of Arizona wouldn’t let me record, I’ve tuned all of that out to focus on Jake — on the details he unspooled over weeks and months.

Jake and I spent more than a dozen hours on the phone, in 15-minute increments, and I visited him twice, for three or four hours each time. He’s a big guy, 6’1”, 195 pounds, and like all the other prisoners, he wore an orange jumpsuit with the letters “ADC,” for Arizona Department of Corrections, in big black letters stenciled on his back and leg. His head is shaved bald and in the midst of a COVID surge, he wore a janky facemask homemade from old T-shirts.

Jake seemed to have earned a certain amount of respect and affection from the other prisoners. During my first visit, people kept walking by and handing him things from the vending machine: snack cakes and a little microwaved hot dog and a bottle of water.

Jake Wideman was sentenced to 25 years to life. He spent 30 years in prison before being released on parole. Then, less than nine months after he was back out in the world, Jake was yanked back into prison. And now nobody knows if Jake will ever get out again. There’s no end in sight.

The details of that part of Jake’s story — the parole violation that landed him back behind bars — well, for now we’ll just say they were very unusual.

Much about Jake's case is very unusual, but much about it is also all too common. And looking at this case, there is a lot we can learn about how the system works, and doesn't, for everyone.

In spending all this time with him, his family, lawyers and others involved in his case, I’ve been trying to figure out what happened.

I’m Beth Schwartzapfel. From The Marshall Project and WBUR, this is Violation: a story about second chances, parole boards, and who pulls the levers of power in the justice system. “There was no motive, just murder.” This is Part 1: Two sons, lost.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Jake’s case takes all the dynamics at play in a typical murder case, and cranks the volume way, way up. Victims’ rights. Political influence. Race. Privilege. Mental health. Senseless violence. How mass incarceration has morphed into mass supervision, with all the same pitfalls and politics.

Jake’s family did not relish opening their personal lives up for public consumption. But with some prodding from Jake, his sister and brother and father each spent time answering my many questions, including: Why agree to talk to me?

Daniel Wideman: This definitely is both, I think, for the love of Jake, but also for the love of justice.

Beth Schwartzapfel: That’s his brother Daniel.

For Jake, talking to me was a leap of faith. I mean, he has a famous writer for a father. It would have been much safer to let John tell it. John would without question see things from Jake’s point of view. But Jake was clear: He wanted a reporter to look at what happened.

Jake Wideman: It's time for the truth to come out and I want to stand on the facts. I don't want anybody to feel sorry for me. I don't want anybody to, you know, take my side out of sympathy or say anything like, “Well, you know, he's been in since he was 16 and 36 years and poor guy.” … I want people to have a conviction that justice needs to be done because of the injustice that has been done so far.

Beth Schwartzapfel: I’m a reporter, so I believe in facts. I believe that if you talk to enough people and do enough research, you can get to the bottom of something. I’m also aware that some facts are unknowable, or what passes for a fact is just a matter of opinion. That you can stack up all the facts, and still disagree about what they mean.

In this case, here’s what we know: Jake Wideman killed a boy when he was a boy. There are mysteries in this story. But the victim, and who committed the murder, are not among them.

ABC15 Arizona’s Dave Biscobing: In 1986, as a teen at summer camp, Jacob Wideman murdered fellow camper Eric Kane. As Eric slept, Wideman stabbed him twice in the chest.

Beth Schwartzapfel: The crime devastated two families.

Ted Bartimus: Two fathers have lost their sons and don't know why.

Beth Schwartzapfel: This is reporter Ted Bartimus.

Ted Bartimus: I was a news reporter for the Arizona Daily Sun back in the 1980s.

Beth Schwartzapfel: I asked him to read from an article he wrote in October of 1988.

Ted Bartimus reading his article: Sanford Kane lost his son to murder in 1986 and noted Black writer John Edgar Wideman lost his son Wednesday to life imprisonment for the same murder.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Now, recordings of court and parole hearings are often comically bad to the point of being almost unintelligible. And you may be shocked to learn that recordings of police interviews from 40 years ago are also not exactly high quality, or captured with audio journalism in mind. So in this podcast, you're going to hear bits of these recordings, but you'll often hear me repeating what's being said. And in some cases, where a recording is not available, you might hear a colleague reading what was said.

With Jake, you'll hear our phone conversations more than anything else, because while I can record phone calls, Arizona wouldn’t let me record inside the prison. I needed special permission just to bring a pen. But I promise that whenever I can, I'll play you the words of people in their own voice.

Now, In 1988 in Arizona, life imprisonment actually meant 25 years to life, which meant that after 25 years, Jake was eligible for parole. In 2011, at 41 years old, he could go before a board and try to prove that he deserved to be free. I first connected with Jake after he’d been before the board more than half a dozen times.

Ellen Kirschbaum during a clemency board meeting: Good morning, Mr. Wideman.

Jake Wideman: Good morning, ma’am.

Ellen Kirschbaum: We are now in session, the Arizona Board of Executive Clemency is about to commence...

Beth Schwartzapfel: Jake told the board he had spent years in therapy, earned multiple degrees, that he worked for decades to make himself a model prisoner and a good man. That something causing him anguish and suffering went unidentified and untreated for decades of his childhood and young adulthood, until he had already spent years in prison. We’ll talk more about that later.

Jake Wideman: All the work that I have done over these years to understand why I did what I did and to heal from my mental health struggles was done to become the best man that I can be and to ensure that I never commit another act of violence in my life.

Beth Schwartzapfel: The parents of Jake’s victim, Eric Kane, still shattered by their son’s murder, looked at the same set of facts and told the parole board they saw only danger — all those words the sign of a master manipulator, Jake’s accomplishments belying a killer who could not be trusted to walk among us.

This is Eric’s mother, Louise Kane:

Louise Kane: This year the murderer has been packaged by professionals. How can one tell what is the real truth, what is his, and what belongs to the lawyers? … If Wideman can do well in jail, then so much the better, but that is where he belongs.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Whose version of the story is the right one?

To some, justice is and will only ever be served when people who kill or harm other people go away and never come back. Or, at least don’t come back until we can be absolutely certain they will never harm anyone again. Which is, y’know, never.

This is Bryan Shea, a deputy county attorney in the office that prosecuted Jake, at a parole board hearing.

Bryan Shea: What will it take for Wideman to have paid his debt to Eric and Eric’s family and to society as a whole? What amount of prison time is enough for this terrible, senseless murder?

Beth Schwartzapfel: I’ve been covering parole boards for years, and answering these unanswerable questions in tens of thousands of cases each year is their very reason for being. And lots of people have plenty to say about how good or not good they are at doing that.

When I published my first big investigation into parole boards, in The Washington Post in 2015, this dark, often secretive corner of the criminal justice system was largely unknown and unexamined. But it’s become increasingly clear as states grapple with ballooning prison populations that these un-elected bodies of mostly political appointees with little or no legal training have, in some states, more power over how much time people serve in prison than judges or juries do.

But before Jake Wideman ever faced a parole board — before Eric Kane was dead and buried and Jake was a grown man trying to tell his version of his story — they were two boys on an adventure.

It was the summer of 1986.

“Matlock” had recently premiered on NBC. President Reagan was in his second term. The fashion of the day included teased hair and giant shoulder pads.

Jake Wideman and Eric Kane had just finished their sophomore years in high school, Jake in Laramie, Wyoming, where his dad was a professor at the University of Wyoming, and Eric in the suburbs north of New York City, where his dad was an executive at IBM.

The two boys had, for years, attended Camp Takajo, a sports camp for boys in southwestern Maine.

It was a high-end camp with all the things: swimming, boating, overnight trips, arts and crafts, woodworking. It was pricey and very exclusive. The camp’s owner, Morty Goldman, didn’t advertise, and filled the 400-someodd spots on word-of-mouth alone. Jake had been spending summers there since he was a toddler because he was Morty Goldman’s grandson.

Later, as police and lawyers tried to piece together what had happened, they interviewed people at the camp. Here’s fellow camper Todd Miller and counselor Bill Hammond describing Jake and the other campers.

Todd Miller: I think basically Jake and maybe one or two other kids are Black.

Bill Hammond: These kids came from backgrounds with private schools.

Beth Schwartzapfel: It was an annual tradition at Takajo that the oldest campers got to go on a tour of national parks in the West at the end of the summer. Early that August, Jake, Eric, two other boys, and counselor Bill had flown into Salt Lake City, rented a blue Oldsmobile, and launched on an epic road trip — to Yellowstone, Grand Teton, and Bryce Canyon.

About two weeks in, a mixup in their itinerary en route to the Grand Canyon unexpectedly landed them about 80 miles southeast, in Flagstaff, Arizona, a small college town in the mountains 7,000 feet above the valley where Phoenix sprawls. Because of its elevation, the weather in Flagstaff resembles New England more than it does the hot desert climate that people associate with Arizona. There are pine trees and crisp fall days and, in the winter, snow.

Ted Bartimus, the Arizona Daily Sun reporter, lived there for years.

Ted Bartimus: Flagstaff tends to be kind of a time-warped community. … A lot of dead heads, you had a lot of cowboys, a lot of lumberjacks. You could walk in certain parts of the community and there's like a time warp. You go back to the ‘60s.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Because of its location on historic Route 66, the town was something of a crossroads. Like the group from Camp Takajo, people often passed through Flagstaff on their way to somewhere else.

John Verkamp: Millions of people are going through there all the time. And a lot of them are fine people, but some of them aren't so fine.

Beth Schwartzapfel: This is John Verkamp, who was, at the time, the county attorney in Coconino County, where Flagstaff is located.

John Verkamp: So we do have more than our share of strange incidents and this was kind of an example.

Beth Schwartzapfel: To Jake’s family, to his teachers and coaches and friends in Laramie, this incident was more than strange. It was shocking. Jake murdered someone?

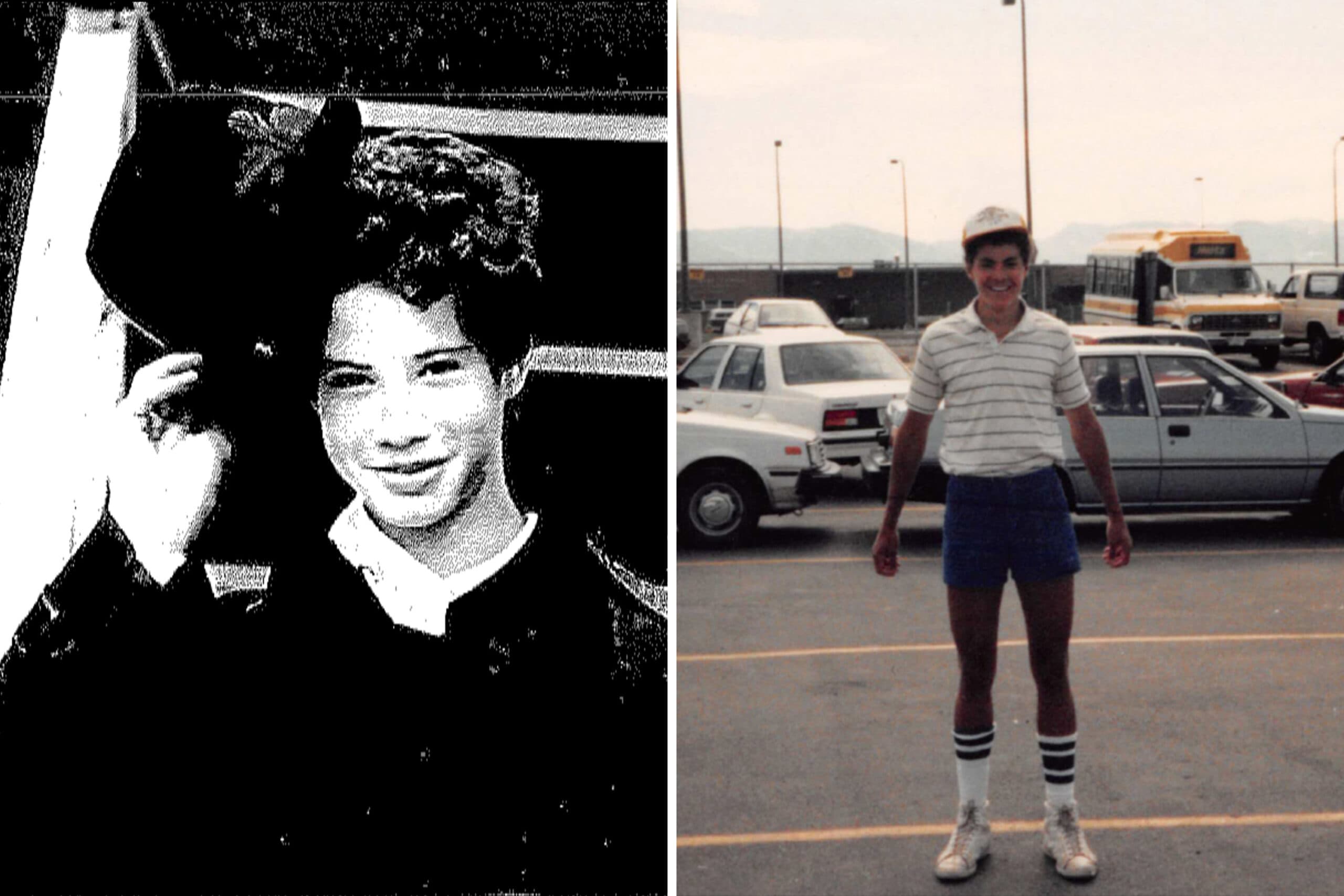

Jake was the second of his family’s three children. Tall, athletic, a talented basketball player. His complexion reflected his family’s mashup of heritages, Black on his dad’s side, part Jewish and part WASP on his mom’s. His hair was improbably blond as a kid, his skin a pale tan. This is John, describing him in an essay he wrote years later.

John Wideman: You were blond then. Huge brown eyes. Hair on your head of many kinds, a storm, a multiculture of textures: kinky, dead straight, curly, frizzy, ringlets; hair thick in places, sparse in others. All your people, on both sides of the family, ecumenically represented in the golden crown atop your head.

Beth Schwartzapfel: His family was part of a close-knit group of families of professors at the University of Wyoming in Laramie, and as a young kid and later a teenager, Jake was known among them as unassuming, bright, and polite.

Janice Harris: There was this tall gangly kid. Very leggy. Just a very sweet, gentle, smiling kind of kid.

Beth Schwartzapfel: This is Janice Harris, an English professor and a good friend of the Widemans’, some years later in an interview with attorneys.

Janice Harris: A very sweet child, a very curious child. Always interested in things. I can remember a particular way he had, if we would be doing field trips, of always asking, “What if this? What if that? What if this?”

Beth Schwartzapfel: As a teenager, Jake was friendly and well-liked. Camper Todd Miller again.

Todd Miller: He seemed like a pretty, pretty normal guy. If you were not in his bunk, seem like just a regular, you know, kid, he was a good basketball player. Nice, nice guy.

Beth Schwartzapfel: But Jake says many of those relationships were superficial — he had very few close friends. That’s because he felt he had a lot to hide.

Todd Miller: Since I was in his bunk for two years, when you're in his bunk and you lived with him a while, he would act strange sometimes for no reason, just bizarre behavior … be hyper, very hyper like he was almost possessed.

Beth Schwartzapfel: In his own mind, Jake thought of these episodes as “adrenaline rushes.” He thought he was hiding them, fooling everyone about the turmoil inside his head. But it would be years too late before he told anyone about them, and many more years before he understood what they were.

Stay with us. We’ll be right back.

Beth Schwartzapfel: We’ve talked a lot about Jake. But the other boy we’re here to talk about is Eric Kane. He had a mop of dark curls and a warm smile. He was the youngest of three children. As kids, his older brother and sister never needed dolls, their mom said, because they had Eric.

At a sports camp like Takajo, Eric Kane stood out for being not very sporty. He had a medical condition as a kid that left him sort of uncoordinated and clumsy. He would dictate his schoolwork to his dad because he found it hard to type.

Even 30 years after his death, there’s still a lot of information in the public record about the kind of boy Eric was, the kind of young man he might have grown up to be. That's because his parents have made sure of that — gathered thousands of letters from family and friends, spoke about him at every public hearing.

And that’s important. I don’t want Eric to be a sort of black hole in this story — an absence instead of a presence. Obviously Eric’s not here to tell me about himself, and unfortunately the Kanes have declined to talk with me. I can understand why — judging from their testimony over the years, their grief is still real and raw. They sent their son off to summer camp and he never came home. As a parent, how do you ever get over that?

I’ve done my best to assemble some details from the letters and decades of testimony and public statements by his family. When he was small, Eric wanted to be a knight. He played piano and guitar. He loved science, and dolphins, and drawing. He had a poodle named Butterscotch. Eric loved to read, his mom said.

Actor reading Louise Kane: I remember, when as a small child, he was stricken with a migraine headache. He lay holding a book the way another child would hold a stuffed animal. He had an insatiable curiosity as long as I could remember, and from the earliest he would ask questions about everything.

Beth Schwartzapfel: In elementary school, he and another friend who quickly outpaced the other kids in reading were pulled out of class to have their own little book group in the principal’s office.

Actor reading friend: We not only read books, we devoured them. We learned to read in the voices of the characters in the stories, we discussed the books, we wrote, and we laughed. He was so very sweet and so deeply kind and so terribly bright.

Beth Schwartzapfel: On the quiet suburban street where they lived, one childhood friend recalled, “We all walked to school together, rode bikes up and down the block, and played in the streets until our parents called us in for dinner.” Another friend said Eric embodied the feeling of the town they grew up in: It was, and he was, “kind, caring, simple and sweet.”

On the Camp Takajo national parks trip, the kids more or less got along, besides for the kind of bickering you might expect when you coop four teenage boys up in an Oldsmobile for hours at a time. Eric, in particular, came in for a lot of teasing.

Here’s camper Todd Miller speaking to detectives later.

Todd Miller: I think it's fair to say probably everybody at some point or another, just, you know, teased him, gave him a hard time. Nothing that really sticks out in my mind.

Beth Schwartzapfel: On the night the kids landed in Flagstaff, they split up to eat dinner at different restaurants. Some of them went back to the motel to watch a Billy Crystal special on TV. Eric went to the movie theater to see “Top Gun.” Jake saw “Ruthless People.”

Clip from “Ruthless People”: Meet Mr. Stone. He wanted to kill Mrs. Stone. “My only regret, Carol …”

Beth Schwartzapfel: Jake and Eric’s movies ended at different times, so Jake walked back from the theater by himself. Counselor Bill Hammond picked Eric up a little later and dropped him back in the motel room he was sharing with Jake. Bill was staying with the other campers Brian and Todd in the room next door.

Much of this information, by the way, comes from old and poorly recorded interviews with Bill, which we got from the county attorney’s office in Flagstaff. As bad as the recordings are, they do help us understand what happened that night.

Around midnight, Jake knocked on the door of Bill’s room. Could he borrow the car keys? He asked. He wanted to sit in the car and listen to his tapes.

Bill Hammond: I said, go ahead, sure, just bring them back when you're done. … I trusted him. I had no problem trusting him and I had no reason not to trust him.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Jake can’t remember what tapes he was listening to that night, but he remembers he loved Motown. Smokey Robinson, the Supremes, the Temptations.

Bill said that while they were on the road, Jake would put on “Sittin’ on the Dock of the Bay,” by Otis Redding on in the car quite often.

Bill Hammond: I looked out there 15 or 20 minutes later and I remember seeing Jake in the car, and the car light was on, and he had the fold-out map in front of him…

Beth Schwartzapfel: Bill figured he’d get the keys back later. It was late, so he got ready for bed. It was the end of another long day on the road. Except for the aggravation of the inadvertent detour, nothing was out of the ordinary. Bill couldn’t have imagined what would happen in the next few hours.

The next morning, when he went to wake Jake and Eric, he found their door ajar. When he pushed it open, neither Jake nor Eric was there. But the bed closest to the door was covered in blood.

He went to get the other campers. Brian, from the room next door, described the scene later to police.

Brian Richards: We looked in the room, there was blood on the wall, it was like a blood handprint.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Bill tried in his mind to rationalize the situation to himself. Maybe someone had had a nosebleed. Maybe one of the boys had gotten sick or injured overnight and the other had driven him to the hospital. Jake liked to play basketball — maybe he had gone out to shoot hoops early that morning and hurt himself. That would explain why the car was gone.

Bill Hammond: And I stood there and thought a minute and looked at the bed covered in blood and thought, that can't be just a nosebleed.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Again, Bill is hard to hear right there in this 37-year-old microcassette interview, but what he says is, “I stood there and thought a minute, and looked at the bed covered in blood and thought, that can’t be just a nosebleed.”

He went back to his room and called the police. This is Detective Mike Cicchinelli. He’s now retired from the Flagstaff Police Department, but on that day in August 1986, he responded to Bill’s 9-1-1 call.

Detective Mike Cicchinelli: When we got the call, we went to a motel room. And what happened is we walked in and there was a knife by the bed and the room was empty and upon further checking it we found that Eric Kane was sitting on the toilet in the bathroom and he had been stabbed to death.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Eric Andrew Kane was 16 years old. And Jacob Edgar Wideman, also 16, was missing.

For a while, police thought that some third party might have kidnapped Jake and killed Eric. What in the world else could explain what had happened?

But like I said, the mystery of this story is not who killed Eric. The mystery of this story is why. Do we understand — can we ever understand — what lived inside of Jake that night? To his friends, his family, to all those who knew Jake, this seems impossible.

Kenneth Ash: Totally surprised. Totally unexpected.

Elizabeth Goudey: Totally unpredictable and inconsistent.

Daniel Wideman: I think I was just in shock.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Jake says he has spent more than a decade trying to understand it himself, and then another decade trying to explain it to the Kanes and the parole board. Years of therapy, and treatment. He’s told me about all of it. And I have hundreds of pages of psych evaluations and reports. We’re going to talk more about all of that. But none of that matters to the Kanes. To the Kanes, it’s all bullshit.

Sandy Kane: None of us know why he brutally murdered Eric.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Their beautiful son is dead and all they hear is lies and excuses.

Sandy Kane: He’s shown other clear evidence of his manipulative behavior. He did this in an attempt to hide the truth: that he has a long term violent history, clear mental health issues from childhood to today, and that he is responsible for a vicious, premeditated murder.

Beth Schwartzapfel: What should happen to kids like Jake? The Supreme Court has said that kids are different from adults — even kids who commit the most serious crimes are less culpable than adults and should be treated differently. Is Jake dangerous, and right where he belongs? Or is he the victim of a concerted campaign by people who hate him?

This story is also about families and the stories they tell.

You see, by the time their son went away for murder, the Widemans were no strangers to American prisons and jails.

John Wideman: I heard the news first in a phone call from my mother. My youngest brother, Robby, and two of his friends had killed a man during a holdup.

Beth Schwartzapfel: Some people were already suggesting that violent crime ran in the family. John Wideman’s brother — Jake’s Uncle Robby — was already serving a life sentence for murder.

Maury Povich on “Current Affair”: Hello, everyone. I'm Maury Povich. Welcome to “A Current Affair.” … Our main story tonight is about the family of a respected author and academic Pulitzer Prize-winner John Wideman. In Wideman’s generation, the “bad seed” was his brother, Robby. …

Beth Schwartzapfel: Had something been passed down through his family over generations? That’s next time on Violation.

If you want more information about Jake’s case, additional documents, photos, and related stories, head over to themarshallproject.org/violation, and, wbur.org/violation.

Violation is a production of WBUR in Boston and The Marshall Project.

Editing of the show comes from Geraldine Sealey, who is also managing editor of The Marshall Project, and Ben Brock Johnson, executive producer of WBUR Podcasts. Additional editing, project management and web production from Amy Gorel. Quincy Walters is our producer. Mix, sound design and original music composition by Paul Vaitkus. Fact checking help from Kate Gallagher at The Marshall Project. Illustrations for our project come from Diego Mallo.

Special thanks to Victor Hernandez, Susan Chira, Margaret Low, Mara Corbett, Laura Hertzfeld, Ashley Dye, Amory Sivertson, Nora Saks, Elan Kiderman Ullendorff, Grace Tatter, Samata Joshi, Marci Suela, Kristen Holgerson, Rachel Kincaid, Brilee Weaver, Dacrie Brooks, Nicole Funaro, Gabe Isman, Ruth Baldwin, Ebony Reed, AJ Pflanzer, Celina Fang, Bo-Won Keum, Terri Troncale, Jennifer Borg, Jason Criss, Celin Carlo-Gonzalez, Ed Klaris, Louise Carron, Ghazala Irshad, and Eli Stern.

I’m Beth Schwartzapfel, your reporter and host. I’ll talk to you next week.