Advertisement

Atop MGH, psychedelics scientists grow plants that could change your mind

Resume

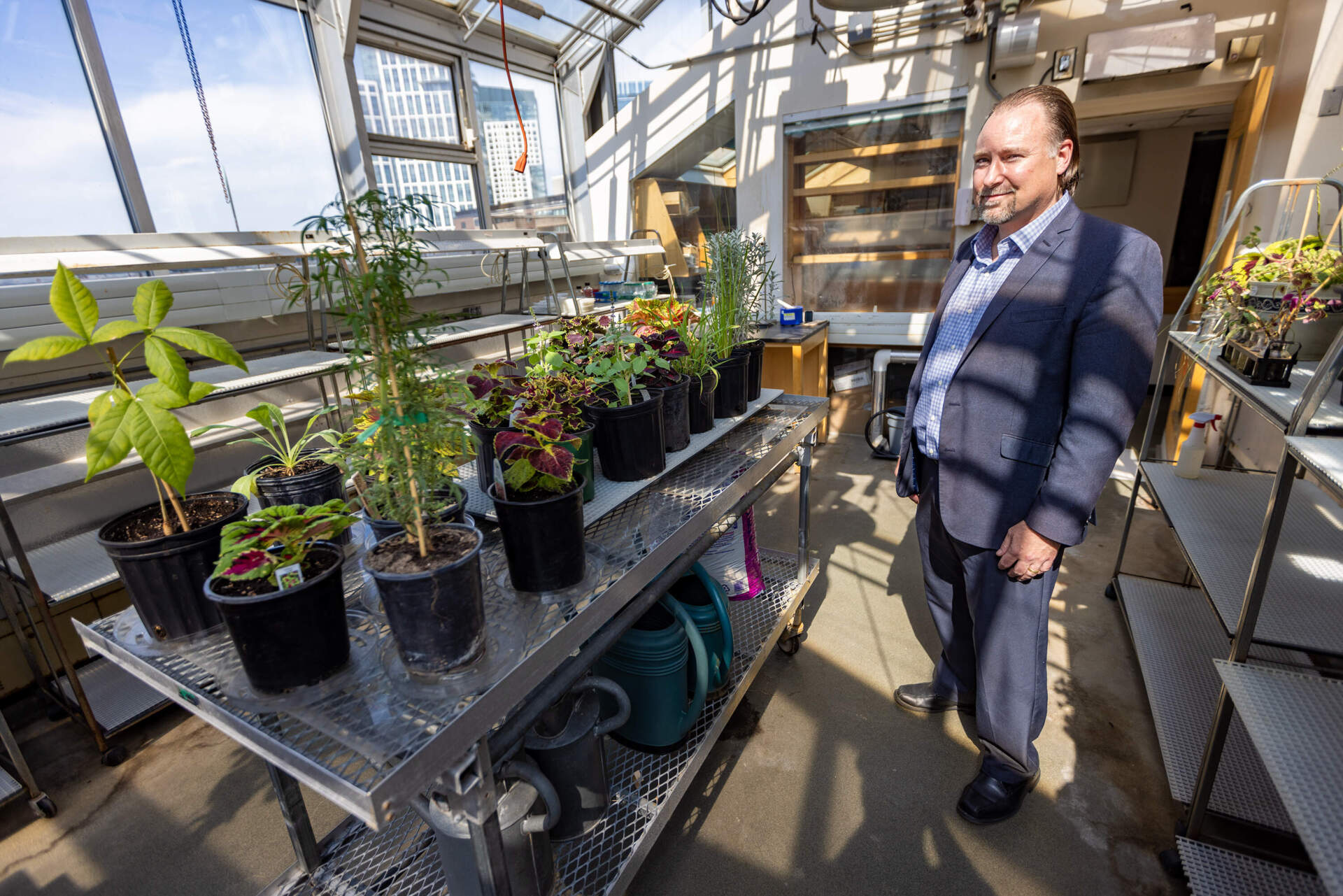

On a rooftop above lab spaces and the sprawling campus buildings of Massachusetts General Hospital, scientists have set up a greenhouse to nurture seedlings with the potential to change how our brains function.

The scientists, from the hospital's Center for the Neuroscience of Psychedelics, are examining how compounds in these plants interact with the human nervous system. They're hoping to answer some profound questions about consciousness and whether the plants can be harnessed to develop new psychiatric drugs.

Leading this work is Stephen Haggarty, a neuroscientist and chemical biologist at Harvard Medical School and a member of the neurology and psychiatry departments at Mass General. He joined the psychedelics research center when it opened three years ago, amid a resurgence in interest in psychedelics and their potential to treat conditions such as depression, anxiety and addiction.

"I personally believe psychedelics have the potential to provide some novel treatments," Haggarty said. "To deliver those as medicine safely is really what we're working through as a larger society."

As part of that effort, Haggarty revived decades-old work in psychoactive substances, meaning substances that affect how the brain works or cause changes in mood or behavior. Psychedelics are a class of psychoactive substances.

In Haggarty's Mass General office, a stone-carved replica of an Aztec god surrounded by various plants sits prominently on a desk. He thinks the sculpture may contain clues about how psychedelic botanicals were used centuries ago.

"That statue really does capture most of the major classes of psychedelic and psychoactive plants," Haggarty said. He includes in that category psychedelic mushrooms, known to the Aztecs as "teonanacatl."

The same Aztec statue appears on the cover of the book "Plants of the Gods: Origins of Hallucinogenic Use," by the late Harvard ethnobotanist Richard Evans Schultes. Schultes is credited with discovering potential medicinal uses for psilocybin, the psychoactive substance found in psychedelic mushrooms.

Beginning in the 1930s, Schultes collected thousands of plant specimens during trips to Mexico and the Amazon. He often worked with indigenous groups, especially their healers, or shamans. He returned to Harvard with reports of hundreds of potentially psychoactive substances that were new to western scientists.

"The field of ethnobotany has a colonial tint to it that is an important aspect to recognize," Haggarty said. "Schultes I like to use as the example, though, of someone who was really revered by the individuals he met. He learned their languages. He lived with them. He ate with them. He became part of their cultures and activity."

But Schultes' work was stymied after psychedelics became popular for recreational use and were banned in the 1970s as part of the U.S. government's war on drugs.

"How do psychedelics really control neuroplasticity? How do they have some of their potential long-term therapeutic benefits?"

Stephen Haggarty

Now, Haggarty is continuing Schultes' research, pouring over documents and the work of Schultes' students. He has already identified more than 50 psychedelic plants used by shamans and other healers that have never before been studied in a lab, and that he thinks show promise for treating psychiatric conditions.

Haggarty is cultivating some of those plants in the greenhouse perched on Mass General's roof.

In one section of roughly 250 square feet, about a dozen plants await lab testing. Some appear to be common ornamental greens; some look like tropical flowering vines. There's even a coffee plant, so researchers can examine the biological effects of caffeine.

"It's a great example of the fact that over time our societies tend to normalize psychedelic and psychoactive plants," Haggarty said. "We can even walk through the Boston Common and identify some of these plants."

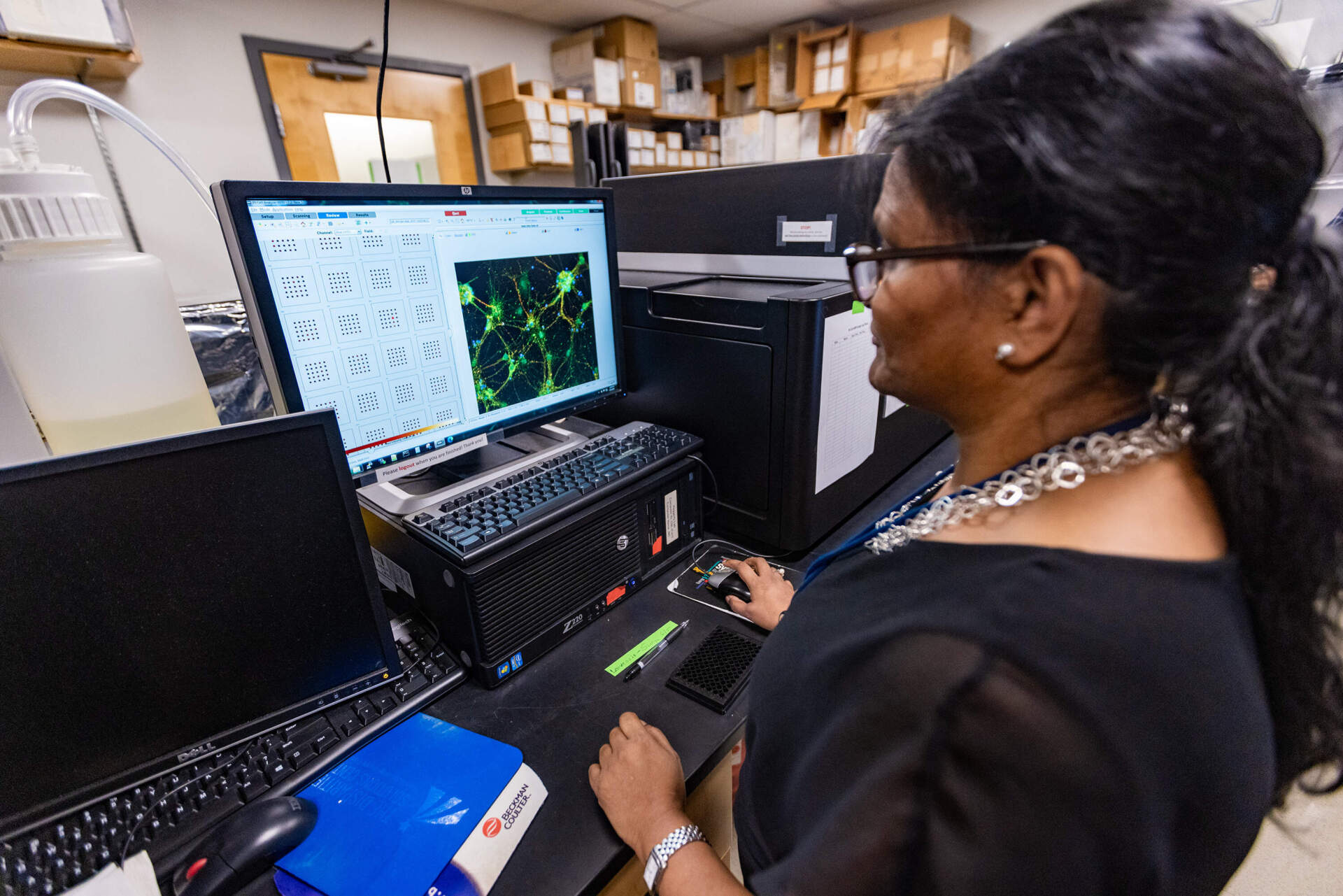

In the Schultes era, researchers would sometimes become test subjects and ingest plant compounds themselves. But today, the plants undergo DNA sequencing before they're tested on human skin cells that have been reprogrammed into stem cells — and ultimately coaxed into brain cells. Haggarty often calls these "mini brains."

Advertisement

"Stem cell technology is one of the most remarkable technologies," Haggarty said.

The "mini brains" help researchers study how psychoactive substances affect neurons, the cells that send and receive signals in the brain, and what's known as neuroplasticity, or how networks in the brain adapt and change.

"There are a variety of very important mechanistic questions that we still don't understand," Haggarty explained. "How do psychedelics really control neuroplasticity? How do they have some of their potential long-term therapeutic benefits?"

Going even deeper, scientists use an automated microscope called the InCell Analyzer 6000. It allows them to observe how synapses, the places where neurons connect and communicate with each other, are affected when they're exposed to different compounds. The microscope, which Haggarty said costs about the same as an average Boston-area home, shows the synaptic density of neurons.

Surya Reis, executive director of the medicinal plant lab at Mass General, said seeing more synaptic activity indicates evidence of neuroplasticity.

"If I have more synapses that are communicating well together, I have better ability for cognitive processes of all sorts, including memory," Reis said. "Any actual function that the brain has will be improved by this activity."

Reis and other scientists study the plants' effects on rodent and human brains. They also study synthetic drug compounds approved as medical treatments to gain a better understanding of how these drugs affect the nervous system.

"To discover something new, we want to understand how some of the old drugs work," Haggarty said. "And one of the challenges I would say in psychiatry is that we don't understand, in fact, very precisely, how many of the existing drugs work."

Because psychedelics remain illegal under federal law, research is limited. Mass General received federal approval for small clinical trials of psilocybin for patients with treatment-resistant depression. The hospital is also investigating a potential treatment that combines psychedelics and MDMA with psychotherapy to treat post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in veterans. The study results are expected this fall.

"One of the challenges ... in psychiatry is that we don't understand, in fact, very precisely, how many of the existing drugs work."

Stephen Haggarty

Haggarty expects it will take years before psychedelics are widely and legally available to treat patients with mental health conditions.

He's closely watching the federal Food and Drug Administration's consideration of an application from the California-based company Lykos Therapeutics to use MDMA, alongside therapy, to treat PTSD. That application was cast in doubt last month when an advisory panel voted against the treatment. The panel found the potential benefits of MDMA did not outweigh the risks.

Haggarty calls the finding a "temporary setback." He said studies of MDMA will lay the groundwork for other psychoactive mental health treatments. And, he said, Mass General is well-positioned to contribute to the future of this research.

Breaking ground on new medical treatments is also part of the hospital's history. In a building adjacent to Haggarty's lab, a dentist from Connecticut and surgeon from Mass General helped make the hospital the first to successfully demonstrate the use of ether as anesthesia.

"Those we consider the first loss of consciousness experiments," Haggarty said. "We'd like to think we're working on enhancing consciousness on the next rooftop over."

This article was originally published on July 18, 2024.

This segment aired on July 18, 2024.