Advertisement

Busing's legacy in Boston, 50 years later

How school segregation survived Boston’s busing

Resume

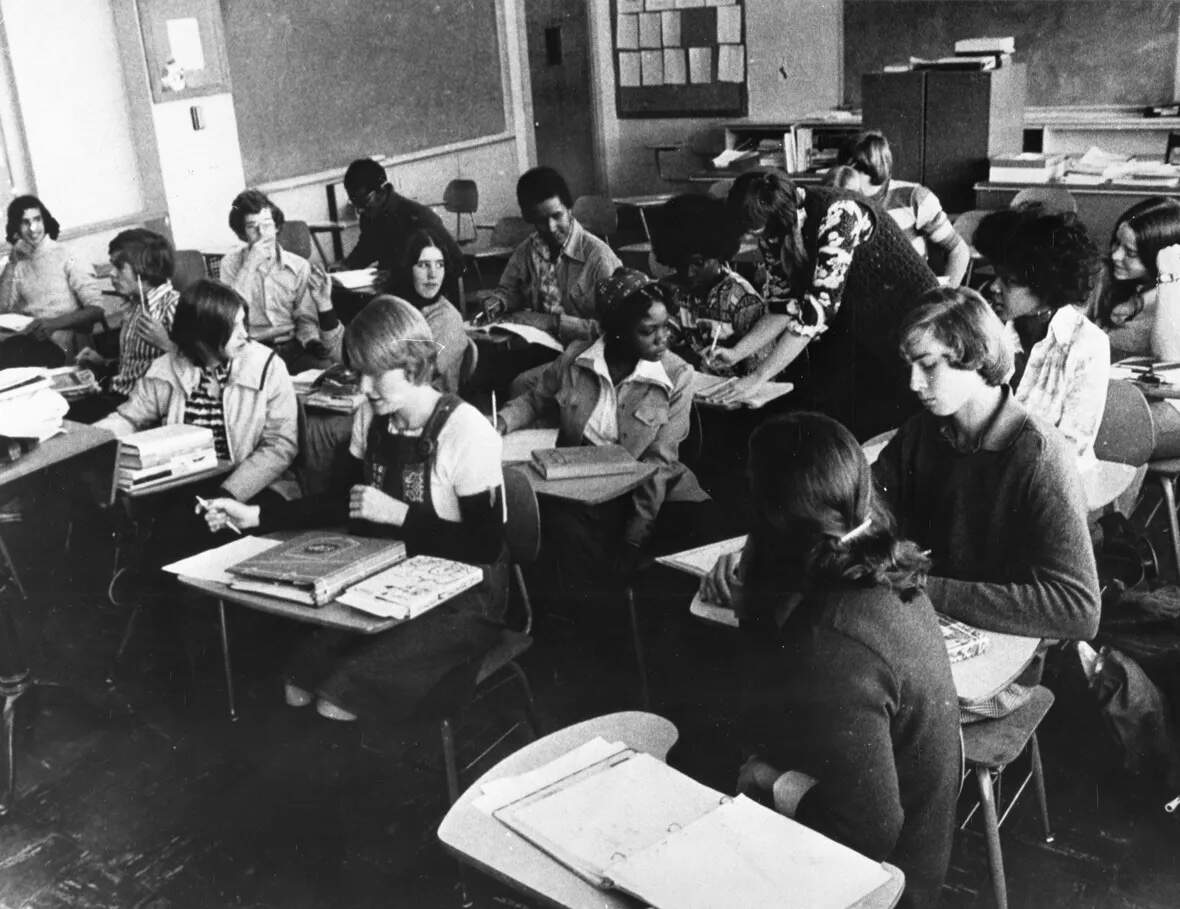

Children at the Lewenberg School in Mattapan studied outdated curricula in a run-down building. Teachers ran out of paper. Bathroom stalls were missing doors. In the spring of 1974, district officials paid little attention to the junior high, whose students were nearly all Black.

But that summer, Judge Arthur Garrity ruled that the Boston School Committee had deliberately created and maintained a segregated education system. By the fall, buses carried White students from Hyde Park to the Lewenberg doors, and their arrival transformed the school. Hallways were painted, bathrooms repaired and new books ordered.

"There was an effort, all of a sudden, when Black and White students were combined in the same classes to elevate the learning and to provide more resources," says Peggy Kemp, who taught at the school until 1978.

Garrity’s desegregation orders carved the city into zones and assigned students to schools so that the racial composition of each school mirrored that of the district. They also reconfigured the system’s leadership by increasing the number of Black educators and administrators.

This hard-won moment may have been the most integrated period in the history of Boston Public Schools. But it was incomplete, short-lived and quickly dismantled.

In less than a decade, the Washington Post would declare the school system “more racially segregated than ever,” and by the start of the new millennium, Boston would drop race as a factor when assigning kids to schools.

White voters in Boston may have supported the desegregation of southern schools hundreds of miles away, but many grew angry and anxious when it came time to integrate their own. Parent after parent would say they supported desegregation, just not the tool that would accomplish it.

The issue, they said, was the school buses — the iconic yellow symbol of American education. Parents opposed busing. Legislators denounced it, as did Boston’s School Committee and Mayor Kevin White.

“It became an all too effective strategy to talk about race without talking about race,” says Zebulon Miletsky, Associate Professor of Africana Studies at Stony Brook University and author of “Before Busing: A History of Boston’s Long Black Freedom Struggle.”

Under the guise of anti-busing, the Boston School Committee obstructed integration efforts, and city officials encouraged their constituents to do the same. A Boston official at one point took to the streets, urging students to stay home from school in violation of state law, according to Robert Pressman, an attorney for the plaintiffs. White residents against “busing” hurled bottles, rocks and racial slurs at Black students traveling to their neighborhood schools.

Advertisement

Leola Hampton was one of those Black students who rode the bus to South Boston High when she was fourteen. She still remembers the angry faces of White residents, who lined the streets daily as her bus pulled in.

“At the root of what happened in 1974, there’s no doubt that racism was at the epicenter,” says Hampton, who switched schools two times over four years, hoping to avoid racial violence and “salvage what was left” of her education.

In response, Washington policymakers retreated from mandated integration by passing “anti-busing” laws.

Buses had been integral to transporting students to and from school for years. Thirty thousand kids — roughly a third of the student population in Boston at the time — had taken a bus to school before any desegregation plan existed.

But when used to integrate schools, anti-busing groups insisted bus rides were too long and “unsafe.”

The Black activists in Boston’s education movement had won the legal battle, Miletsky says, but they were losing the public-relations war.

By 1975, roughly half the city's students were expected to ride a bus to school each morning, a trip along Boston’s compact streets that averaged 15 minutes. Transportation was only one aspect of the plan to integrate the city’s schools, which spanned 400 orders and included upgrades to facilities, the creation of Magnet schools and richer parent engagement.

However, rhetoric surrounding busing was such a distraction that it stole the focus and became a driving force in shifting the legal landscape.

Fears about “busing” helped propel Richard Nixon to the presidency in 1969. To that point, the court system had been a dominant driver in desegregation, strengthening school integration efforts. After Nixon appointed four conservative Supreme Court Justices during his term, that same system was poised to weaken them.

The federal court quietly vacated Boston Public Schools in 1985. In the decade since spurring district officials toward integration, their efforts had stalled. Changing demographics and an increasingly conservative legal landscape hampered desegregation, even as the standard by which it was measured fell.

A “racially imbalanced” school in Massachusetts, according to a 1968 state law, is one in which more than 50% of students are not white. Garrity’s 1974 desegregation orders applied this definition. By 1985, however, schools were not considered out of compliance with court orders unless more than 80% of the students were the same race.

The wavering standards were chalked up to demographic shifts.

Boston Public Schools now had half the number of white students it did in the early 70s. White families previously trickled and now flooded out of the system. (Black families left, as well, but not as many).

To truly integrate schools, students would need to cross the invisible border separating Boston from its outlying suburbs. However, the Supreme Court had struck down city-suburban busing in 1974.

When the court was deciding whether to vacate the district, one in 10 Boston schools remained segregated according to the 80% standard. Many of these were located in East Boston, a White enclave that had been exempt from integration due to geographic isolation.

The others were located in Dorchester and Hyde Park, neighborhoods that together housed half the district's Black students. The schools in these areas were some of the most dilapidated in the system. According to a court memo, the racial isolation in these schools threatened students’ rights.

Without a metropolitan option, however, the courts concluded that further integration in Boston schools was unlikely to be achieved.

Though Judge Garrity argued that the school committee had never “fully implemented” the desegregation plan, it was no longer under any pressure to achieve integration.

“In essence, courts began ending judicial oversight of school boards on the finding that continuing efforts to desegregate schools would be tough—not on the finding that school boards actually had successfully desegregated their schools,” Khiara Bridges wrote in her 2018 book "Critical Race Theory: A Primer."

When Garrity returned authority to the Boston School Committee in November 1985, he warned that the city had "considerable unfinished business.” However, the School Committee and its president at the time, John Nucci, behaved as though the ruling meant “mission accomplished.”

The NAACP had a different interpretation.

“Many of us will not be sleeping too well at night for some time to come until the school committee establishes the fact that they can be relied on,” Jack E. Robinson, President of the Boston Branch of the NAACP, told the Boston Globe.

The fourteen Black parents who filed the original lawsuit felt that progress had been made, but it was insufficient, according to their attorney, and they requested continued court involvement.

Boston Public Schools Superintendent Laval Wilson said the court’s decision created an opportunity to give parents a say in where their children went to school.

A few years later, Boston changed the student assignment process. Parents could now choose from among dozens of schools, so long as it didn’t upset the racial balance.

School choice was increasingly attractive to families, who had grown worried about the quality of the city’s schools.

To read news of Boston schools during the 80s was to hear about a system drowning in "chaos." Test scores "plunged" and dropout rates "soared." The district sped through eight superintendents in the 11 years since desegregation began. Drops in enrollment and tax cuts left Boston schools in a financial crisis. In the early 80s, the district laid off a thousand teachers and closed dozens of schools.

Parents who had become disenchanted with the limited impact of Boston’s attempt at integration now emphasized school quality.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Department of Education whipped Americans into a frenzy about the "rising tide of mediocrity" in their schools with the publication of “A Nation at Risk. The Boston Municipal Research Bureau published its own report titled, “The State of the Boston Public Schools: A Pessimistic Diagnosis by the Numbers.”

If schools were that bad, policymakers argued, parents should be given the opportunity to choose a school for their child.

An alternative desegregation technique was introduced to districts across Massachusetts and around the country. Controlled Choice allowed parents to pick among schools in their geographic zone, so long as the schools remained integrated.

The plan was first adopted by Cambridge in 1981, and dozens of cities around Massachusetts soon rolled out similar ones. Boston joined them in 1989.

Controlled Choice divided Boston into three zones, drawn to include a diversity of students. Parents ranked their top schools. Children were enrolled in their first choice unless it upset the racial balance.

The four Black members of the Boston School Committee did not support the plan, saying it would lead to resegregation, send the city back to court and penalize the schools that parents did not choose with lower enrollment and decreased funding.

Most parents, it turned out, liked the plan. More than three-quarters of students who ranked a school were assigned to their first or second choice. Less than 10% of students were administratively assigned to a school.

Families who had felt constrained by the student assignment process during desegregation were glad to have more control over their kids' education.

White parents huddled in auditoriums and marching through streets had argued for school choice since Garrity’s first court order. But Black families also had become interested in the idea, feeling frustration about busing their children to schools that they felt were no better in quality — and had no more White children — than the ones down the road. A handful of Black parents in 1982 had gone so far as to ask Garrity to scrap the student assignment plan altogether.

Who knows what would have happened if Boston hadn't dropped Controlled Choice in 2000? Across the river, though, Cambridge continues to use a version of the plan and its schools are far more racially diverse.

Parents and politicians gathered in the towering, four-columned building on Court Street in the summer of 1999 to urge the Boston School Committee to stop what one man described as a “total betrayal of the struggle that has gone on in this city for the last 25 years.”

Several universities faced challenges to their affirmative action policies. Boston had recently become the first K-12 school district to run into a similar legal assault.

Michael McLaughlin's 12-year-old daughter, Julia, had applied to Boston Latin, one of the city's three elite exam schools. Benjamin Franklin was a student there. Ralph Waldo Emerson, too.

Julia, who is White, was rejected. So her father sued the district in 1995, claiming the 35% of seats set aside for Black and Latinx applicants — in a city where 80% of students were not White — violated her civil rights.

The case flipped the Fourteenth Amendment on its head. Though written in race-neutral language, the 14th Amendment was ratified during Reconstruction to expand and protect the rights of formerly enslaved Americans. Now White parents were chipping away at those rights with claims of reverse discrimination.

Judge Garrity presided over the case. In an ironic historical loop, the man who had ordered the desegregation of Boston's public schools concluded that an admissions policy created under his orders was "constitutionally suspect" — only a year after the case had officially closed.

A series of similar lawsuits against Boston Public Schools followed, some spearheaded by McLaughlin himself even after his own daughter uneventfully entered Boston Latin as an 8th grader in 1996.

Meanwhile, the Department of Education weakened its ability to monitor integration in the ‘90s by dismantling the Bureau of Equal Educational Opportunity.

By the summer of 1999, the Boston school committee worried that Controlled Choice would not hold up in a court of law. Now they were deciding whether to drop the consideration of race in student assignments completely.

A Black woman with cropped hair walked to the front of the school committee chambers. A handful of people applauded before she said a word. Her journey to this microphone had been a long one.

Jean McGuire worked for Boston schools in the ‘60s — first as a teacher, then as a counselor. She participated in the Black Education Movement, co-founding Boston’s voluntary school desegregation program and becoming the first Black woman on the school committee in 1981.

"I implore you … to take the high ground; the ethical, moral and intellectual high ground in this case,” McGuire told the committee. "This short 25 years that we have experimented in trying to provide equity and improve this school system’s outcomes for children is a very short time compared to the busing of black people from Africa in chains."

If McGuire had still been a member of the school committee things might have turned out differently. But she had been removed, along with three other Black leaders who rose to prominence during Boston desegregation, when then-Mayor Raymond Flynn turned the elected committee into an appointed body.

The motion passed.

Though the system for assigning students to schools remained in place, its purpose — racial integration — was stamped out.

Between 1993 and 2005, Black student enrollment at Boston Latin was cut in half. In the years following the decision, Boston schools grew increasingly segregated.

More than 200,000 schools in Massachusetts are racially segregated today, according to a 2024 report from the Racial Imbalance Advisory Committee. Though segregation violates state law, local districts and statewide boards have failed to address it.

This story was originally published by The Emancipator and is part of an editorial partnership between WBUR and The Emancipator on the 50th anniversary of a federal judge’s ruling that led to busing of schoolchildren in Boston.

This segment aired on June 19, 2024.