Advertisement

Commentary

The power — and comfort — of rituals

While preparing breakfast, I make a point to gaze out my apartment window and catch any rabbits grazing on the lawn. Seeing them placidly dine along with me provides a comforting sense of connection to the natural world. Breakfast with bunnies is Step 2 in a years-old morning routine, Step 1 being pre-dawn exercise while watching the news on Channel 5. Finally comes Step 3, my work commute from Belmont to Boston: chatting up familiar faces on the bus and train, then abandoning the Green Line 20 minutes from my office stop to enjoy a leg-stretching, mind-clearing walk up Commonwealth Avenue.

Each act of this script, which has mapped my life for years, provides health and contentment, while activating a pleasant drip-drip of nostalgia. Admittedly, adhering to a liturgy of living comes naturally to a lifelong Catholic, trained in the familiar, weekly rhythm of the worship formulary. From eating special dishes every holiday to adhering to an early-to-bed-early-to-rise schedule, I observe the march of seasons through the ordered regularity of living. Yet it turns out that even atheists and free spirits who favor a smorgasbord approach to life can benefit from the practice of ritual.

“The Ritual Effect,” by Harvard Business School professor Michael Norton, summarizes his and other scholars’ interviews with tens of thousands of people across demographics and countries. “In realms personal and professional, private and public, and in encounters that cut across cultures and identities,” Norton writes, “rituals are emotional catalysts that energize, inspire and elevate us.”

Norton’s 288 pages lay out how and why rituals generate such varied emotions, and how important that is for our psychological well-being. Indeed, that emotional rush distinguishes a ritual from a mere habit. Habits are unthinking actions; they may be good for us, like brushing our teeth or eating our fruits and veggies. But rituals are deliberately selected ways of performing these actions — the “how” of doing them, per Norton — that invest an action with emotional satisfaction.

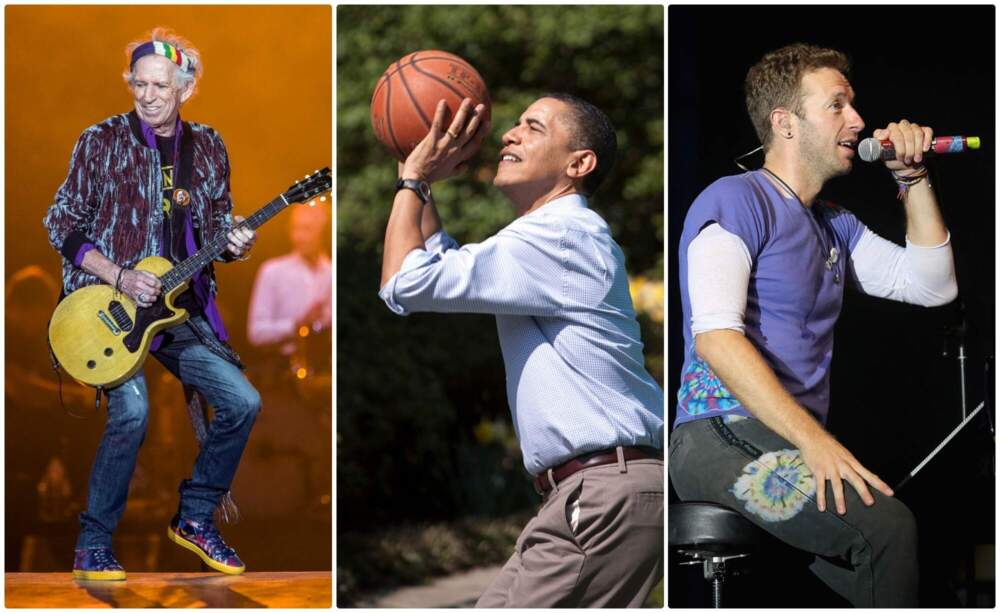

I’m relieved to learn that compulsive repetition isn’t the province of obsessive-compulsive people or folks with nothing better to do. Norton lists famous overachievers’ prerequisite rituals for work: Keith Richards must have the first slice of a shepherd’s pie before performing with the Rolling Stones. Coldplay’s Chris Martin didn’t walk on stage to make music without precision-brushing his pearly whites beforehand. And every Election Day, Barack Obama insisted on playing basketball with friends to distract him from worrying about how the voting would go.

I possess neither musical creativity nor the fire in the belly required to reach the presidency. But I do get these folks’ devotion to ritual. It anchors us with security amid our impermanent, ever-changing and often fretful lives. As the Boston Globe’s religion columnist years ago, I profiled a group of atheists and agnostics that gathered Sundays near Harvard Square to listen to and discourse with a speaker about some public issue. One regular attendee acknowledged the parallel to weekly religious services. Both believers and non-religious, he said, benefited from communal rituals.

There are no more avid ritualists on the planet than parents. Those with young kids discover daily that ritual greases the gears of childrearing — never more so than at bedtime. Reading all seven Harry Potter books to my boy — twice — while trying to remember the different voices I concocted for each character might have exercised my brain against early dementia; it certainly made for two years of ritual joy. I’ll also treasure to the grave my recollections of making up Scooby-Doo bedtime stories based on villains he invented. (The Lemonade Spilling On People Monster stands out in my memory.)

And while my gifts do not include creating music to sustain the soul, I, like some other parents, sang favorite hymns as lullabies for Kieran. I regularly sang “Be Not Afraid.” The song’s gentle invocation of the Beatitudes offered reassurance to my child, as he drifted to sleep, that all would be well when he opened his eyes in the morning:

Blessed are your poor, for the kingdom shall be theirs,

Blessed are you who weep and mourn, for one day you shall laugh.

I don’t mean to romanticize what can be an exhausting ordeal. As with any child, ours sometimes required a ghastly amount of time before letting the arms of Morpheus hug him to sleep. On those nights when it seemed as if I’d never get to bed, even I got a little sick of hearing my own voice. But when it finally succeeded in putting him down, I knew that exertion had done what all rituals do for people — bond us together, in this case, father with son.

These bedtime customs commingled the beauty of religious and literary ritual with the obligatory rituals of fatherhood. Mixing business and pleasure: There’s a ritual that can benefit anyone.