Advertisement

He Was Too Nervous To Walk In His Own Neighborhood As A Black Man. Then His Neighbors Walked With Him.

Resume

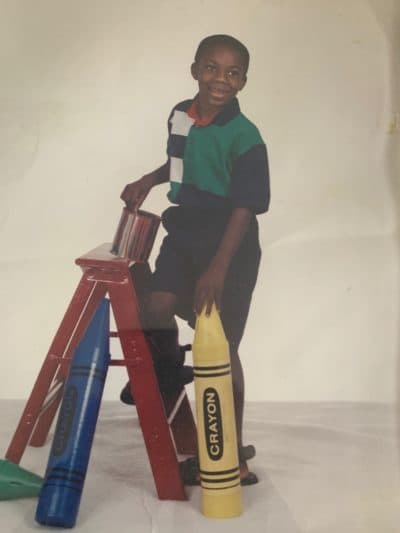

Shawn Dromgoole, 29, still lives in the same house where he grew up in Nashville, in what used to be a predominately black neighborhood.

"I could walk by myself to Aunt Lily’s house or Aunt Cassie's house or Aunt Hilda’s house without any worry. As a kid, it was that safe," Shawn said.

That started to change when Shawn was a teenager. He remembers one particularly incident when he visited a new antique shop that opened up in his neighborhood. Shawn and his grandmother had always loved antiquing together. This time, he decided to go into the store by himself.

"I walked in and they threatened to call the police on me," Shawn said. "I had to call my grandmother to come get me."

Over the years, as the neighborhood became more gentrified, many of Shawn's black neighbors left. A lot of them were getting older and couldn’t afford to keep their homes. More white families moved in. The same neighborhood that once felt safe for Shawn started to feel different.

"A couple of years ago, the police stopped me for walking while black and they followed me home to make sure that I lived in the neighborhood," Shawn said. "The neighborhood has changed that much."

Behind that frustration was real fear, especially after the murder of 25-year-old jogger, Ahmaud Arbery in Georgia. Shawn couldn't help but think how it could've been him. His fear became crippling. He was too nervous to go outside.

"I wanted to go on a walk and I couldn't. I couldn't make it past the front porch. I went back in the house and closed the door," Shawn said. "I’m my mama’s only son. I can't risk her losing me. Who's gonna take care of my mom if I'm gone?"

Then, in late May, Shawn shared how he felt on social media. He said that as a 29-year-old, 250-pound black man, he was afraid to walk in his own neighborhood.

To his surprise, a lot of neighbors responded. Many asked if they could walk with him. He didn't think much of it and instead made plans to meet up and walk with a mentor who lives nearby. But when he showed up to meet her, he saw 75 other people waiting for him.

"I was speechless. I literally did not know what to do," Shawn said.

The next week, Shawn organized another walk. This time, around 1,000 people showed up. It was a diverse crowd of people wearing masks and trying their best to physically distance. It was a surreal, life-changing experience for Shawn.

Advertisement

"I feel like I found my voice. I feel like I've literally found my calling," Shawn said. "These are things I've been passionate about my whole life. I just never knew how to do it."

Now Shawn is planning to organize walks in different cities across the country. He wants to spread a message of unity that encourages people to get to know their neighbors.

He admits he's been criticized by some friends, who find his plan too idealistic during a time of mass protests. But the gravity of the moment isn’t lost on Shawn. He says fighting racism and violence takes work on several different fronts.

"I want to do something to make it better. I want to be able to tear down the structures," Shawn said. "We've got to move in our lanes. It’s a puzzle. Protests make the noise because if you make the noise, then I can have the conversation."

For Shawn, that conversation starts with the people closest to you: your neighbors.